Robert Wyatt performs in a knitted mask on French television. One of the more underrated progressive rock groups from the ’70s Canterbury Scene, Matching Mole was a short-lived […]

5 Prog Albums That Are Actually Good

Jocelyn Romo shares five essential selections that go beyond the preconceptions of what prog can be.

The very word makes any number of music fans recoil: Prog. The jazz-influenced, classical-inspired genre took the world by storm from the late 60’s into the mid 70’s. Rising meteorically before crashing down with the arrival of punk rock, the era left endless albums and hyper-specific subgenres in its wake.

Prog was loathed by many critics, who thought it extravagantly conceptual and needlessly technical. Many of the overly long songs that came to define prog music were so pretentious that the raw, bursting energy of rock and roll was annihilated by 20-minute floods of synthesizer solos and towering guitar riffs.

But beyond the caricature of prog rock — the ostentatious live shows, the fantastical lyrics, the ambition and the eccentricity — the genre also inspired untamed experimentation, giving musicians a pass to explore the outer limits of what popular music could represent.

The best albums offered something more interesting and insightful than what rock and roll, jazz or classical music could represent, its subgenres themselves standing alone beyond the label of “progressive.” Below, five prog albums that go outside the traditional notions of what “prog” can be, and that might help you redefine what the genre can be.

Aphrodite’s Child – 666 (1972)

A unique and impressive landmark in early progressive rock and the most traditionally “prog” album on this list, 666 is a double album based on The Apocalypse of St. John in the New Testament. Conceived by Vangelis Papathanassiou and Greek actor Costas Ferris, it took more than a year to record and complete. As Vangelis gradually took over the project, the band became uncomfortable with the change of direction, so much so that when it was finally ready for release, the members had split and each was working on a solo album.

While the musical core of 666 is centered on uniting opposite genres such as rock, folklore, electronics and jazz, the shorter tracks on the albums are experimental interludes that, with its spoken elements, hardly qualify as music at all. The album’s feature track, “All the Seats Were Occupied,” is nearly 20-minutes long and occupies all of side four. The work builds gradually as it chaotically combines influences, songs and sounds within the album into a climactic jam with elements of electronics and space rock. It would also be Vangelis’ first major instrumental composition, something to note as he would later be known for his film soundtracks like the Oscar-winning soundtracks Chariots of Fire and Blade Runner.

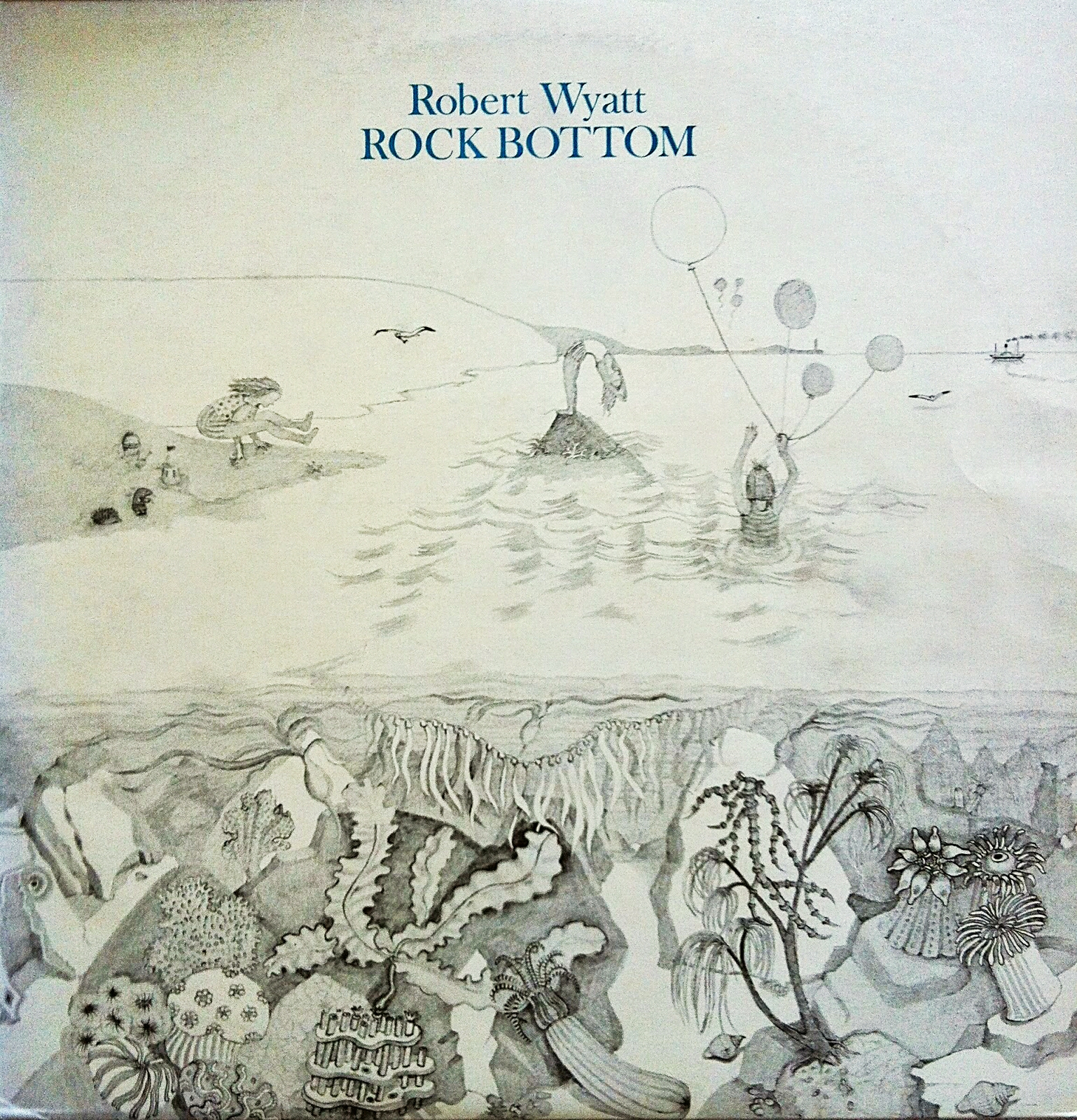

Robert Wyatt – Rock Bottom (1974)

In 1973, Robert Wyatt’s trajectory was upended after he fell from a fourth story window. It rendered him a paraplegic, and the former drummer of the jazz-rock band Soft Machine suddenly had to reconsider and rearrange his whole life, and reframe and restructure his approach to music and living. His second album, Rock Bottom, is the story of him coming to terms with his new condition. Fueled by the deep wells of human spirit, he became inspired and transformed by his accident, which offered him a kind of black slate with which to begin anew.

An album that falls under “Canterbury Sound” strand of prog rock, Rock Bottom dips its toe in what would become an unstoppable solo career full of experimentation, quirky compositions, jazz leanings and avant-garde tendencies.

“Sea Song” opens the album in an ethereal, delicate and dazzling way. Both dense and melancholy, it sets the tone for an album that thrives on emotion. By the time you reach “Little Red Robin Hood Hit The Road”, Wyatt has taken you through some his most angst-driven low points — dissonant soundscapes featuring musicians such as Richard Sinclair (Caravan), Hugh Hopper (Soft Machine), Fred Frith (Henry Cow) and Mike Oldfield. Rock Bottom travels like a surreal freefall into Wyatt’s emotional landscape: Sometimes he reveals tension and desperation, but he tempers that by soaring into new, liberating and fantastical territory. The result is an album of life-changing songs that are charming and sometimes humorous, yet immensely moving and evocative.

Henry Cow – Unrest (1974)

Initially created as more of a collective than a subgenre, “Rock in Opposition” (ROI) was founded by British art rock group Henry Cow in the late ‘70s as an organized means of exposing issues in the music industry, specifically bringing to light a system that found musicians working outside the label system go completely unrecognized in the larger marketplace. ROI also very loosely categorized a unique brand of progressive music.

Though notoriously hard to pin down musically throughout their career, Henry Cow’s sophomore album Unrest saw the group take elements of their debut album, considered closer to more traditional “Canterbury Sound” prog, and pushed it to new musical and intellectual extremes, incorporating higher elements of avant rock, improvisational jazz and classical chamber music. Even Robert Christgau, the self-proclaimed “dean of American rock critics” who carried in him a pure hatred for prog music, wrote of the album: “This demanding music shows up such superstar ‘progressives’ as Yes for the weak-minded reactionaries they are.”

There was definitely no weak-minded ostentation, instrumental superfluity or musical ornamentation coming from the guitar of Fred Frith, a founding member of Henry Cow. Where most prog had some level of inspiration from Western classical music, Frith was more Béla Bartók than Beethoven. He composed based on Bartok’s use of the Fibonacci numbers to structure the musical body of “Ruins.” Generally used in art and architecture, the numerical sequence responsible for the “golden ratio” is found in natural formations: the spiral of a snail’s shell, flower petals, a whirlpool, the shape of a galaxy. Musically, his compositions suggest this too: generally, they present a well-crafted melody early on, which unravels into a spiral chaos before meeting itself once again in a wildly unpredictable, yet highly organized, musical realm.

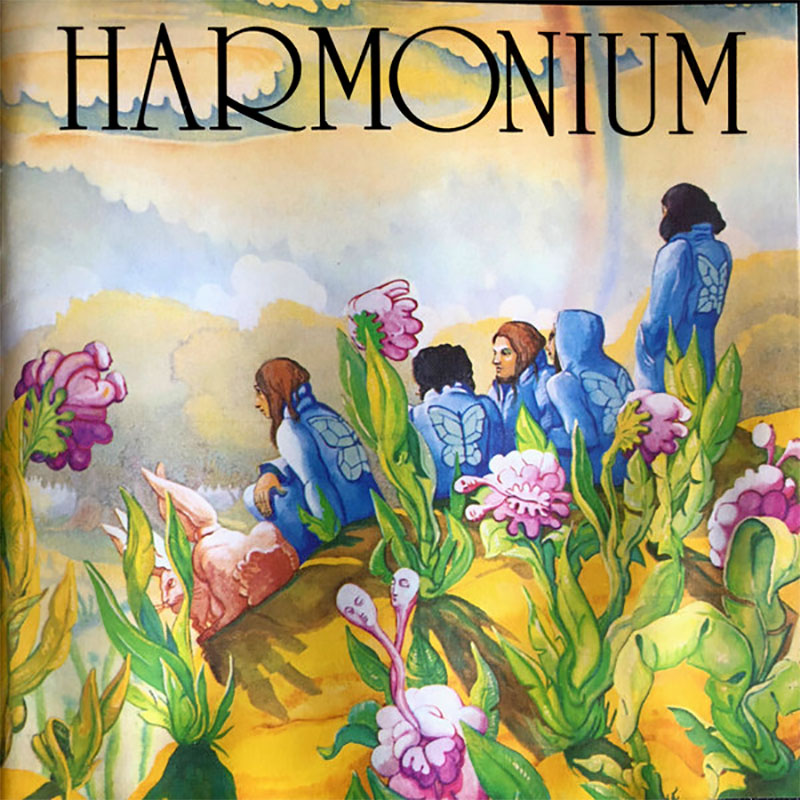

Harmonium – Si on avait besoin d’une cinquième saison or Les Cinq Saisons (1975)

Though short-lived in their musical career — they released three studio albums between 1974 and 1976 — French Canadian symphonic prog/folk group Harmonium didn’t hide their pastoral influences. But for their second album, bandleader Serge Fiori showed greater ambitions after being tagged as just another folk band upon release of their self-titled debut. Serving as a sort of conceptual sequel to Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, Les Cinq Saisons embarks on a magic and reflective journey from Spring through Winter into a mythical “fifth season.” Through the course of the album, Harmonium creates complex symphonic structures, overwhelming musical landscapes and ambient atmospheres full of lush keyboard work from electric piano, mellotron, synthesizers, melodic flute work and unassuming vocals. There’s scarcely a percussive sound on the album..

Part of what makes Les Cinq Saisons special is the lack of ostentation. Its simple melodies manage to demonstrate the virtuosity of its musicians, who transform them with depths of imagination.

The album closes with its conceptual cornerstone – the seventeen minute “Histoires Sans Paroles.” The mostly instrumental epic leads with flute and mellotron, which repeat a floating, romantic and slightly melancholy theme through the course of the song. The melody morphs so effortlessly that the sudden change of landscape can take you by surprise. As a whole, it’s an album that imagines prog music as a more beautiful world, and it’s a realm that will keep the most seasoned daydreamer locked in reverie.

Klaus Schulze – Time Wind (1975)

Progressive electronic music carried many of the signatures that came to define prog rock: long-form songs with heightened conceptual ideas and complex instrumentation that, ideally, delivered moving experiences. One of the earliest innovators of progressive electronic music, Klaus Schulze found his first major commercial success in 1975, reaching a global audience with his fifth album, Timewind. A former member of Ash Ra Temple and Tangerine Dream, Schulze’s breakthrough featured Dali-esque artwork reminiscent of the surreal album covers of more rock-oriented bands. The album became an instant hit for lovers of both electronic and progressive music.

More evidence of the classical music inspiration on prog, Timewind is dedicated to Richard Wagner and the titles to both side-long extended compositions reference the life of the composer. “Bayreuth Returns” names the Bavarian town where Wagner had an opera house built for the first performance of his legendary Ring Cycle; and the Wahnfried mention in “Wahnfried 1883” is the both the name of Wagner’s home and burial grounds in Bayreuth and the year in which he died. These two expansive and hypnotic tracks, both similarly structured but bearing little resemblance otherwise, combine on Timewind to create an astounding experience that slowly unfolds to reveal layers of meditative synthesizers, contemplatively shifting and drifting across windswept synthetic soundscapes.