Try fitting a cathedral in a suitcase. That’s the quiet determination behind American Masters turning its lens on Sun Ra, an artist whose life and work feel so […]

Henry Threadgill: From Chicago’s Streets to the Outer Limits of Jazz

In Hamburg, 1988, Threadgill’s Society Situation Dance Band turned a crowded stage into a carnival of sound, a glimpse of how far he was willing to push jazz into new territory. Watch the set.

The deeper you dig, the more you give yourself over to curiosity and instinct, the more likely you are to stumble into sounds that feel less discovered than unearthed from some other dimension. They shimmer like half-seen constellations, pull you toward unknown galaxies, and send a live current of starlight racing through your spine.

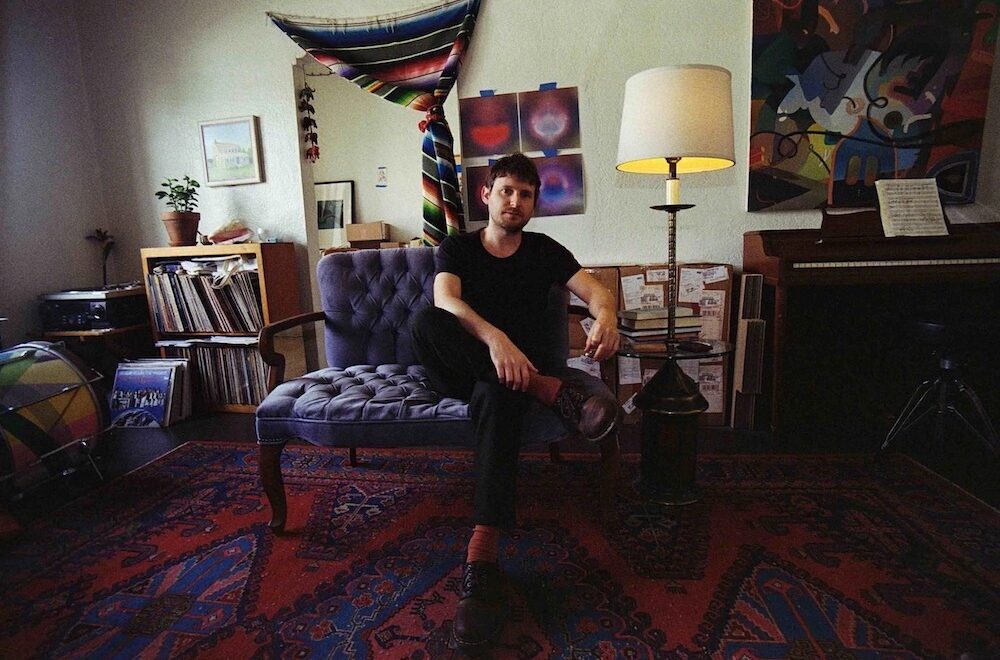

For the past few months, Henry Threadgill and his many dynamic outfits have been filling my listening room with deep, algebraic compositions and ridiculously heavy jazz jams. Few can saturate a space with such density and imagination. A founding member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) Threadgill has spent decades bending form into unexpected shapes, marrying fierce rhythm with lyrical abstraction.

Born in Chicago in 1944, Threadgill grew up steeped in the city’s musical fabric, from gospel and blues on the South Side to the brass of school marching bands. He studied flute, saxophone, and composition at the American Conservatory of Music, and by the early 1960s was performing in clubs and church ensembles while absorbing the avant-garde stirrings around him.

When the AACM was founded in 1965, he was among its earliest members, joining peers like Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, and Lester Bowie in a collective determined to stretch the boundaries of jazz. For young musicians like Threadgill, the AACM felt less like a club than a revolution, a self-made space where community, experimentation, and independence mattered as much as virtuosity. Just as his own ideas were beginning to take flight, the draft sent him into the Army in the mid-1960s, where he played in military bands before returning to Chicago.

When he came back from the Army, Threadgill dove straight into Chicago’s experimental scene, reconnecting with the AACM and pushing deeper into its possibilities. In the early ’70s he formed Air with bassist Fred Hopkins and drummer Steve McCall, a trio that didn’t just swing or freewheel but managed to fold both together with grit and imagination. One night they’d tap into ragtime or a blues figure, the next they’d stretch it until the seams burst, all of it carried by Threadgill’s sharp-edged alto lines and the restless intelligence of his writing. Even in that stripped-down format, you could hear the composer in him, always sketching new shapes inside the sound.

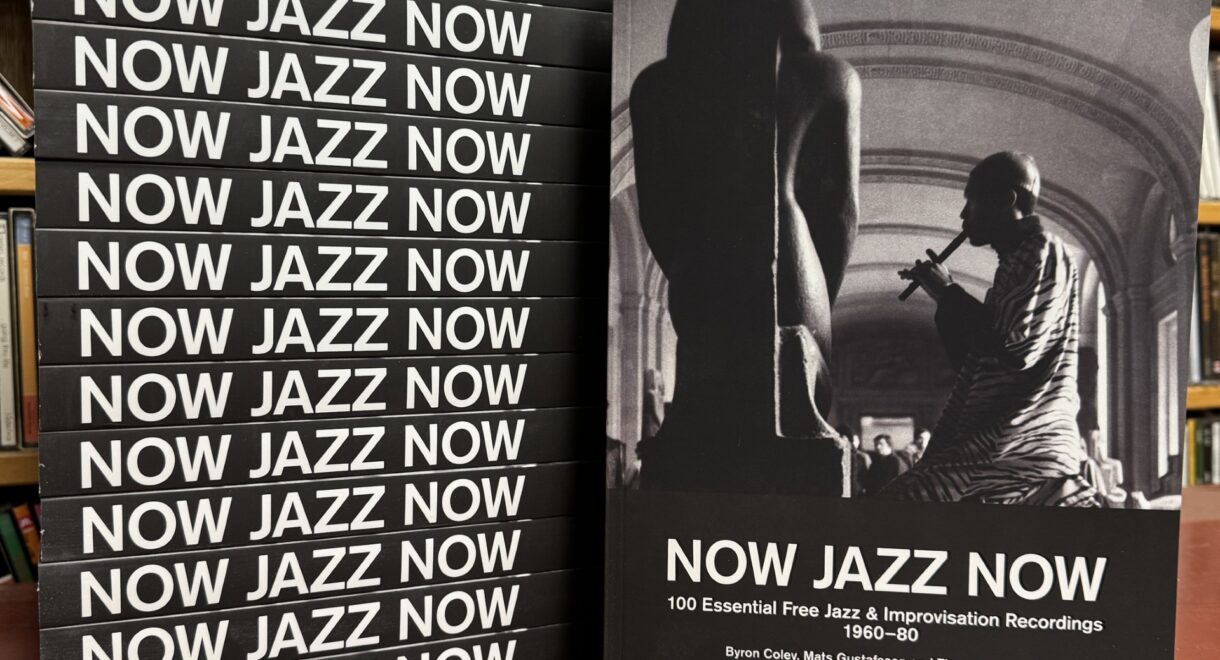

By the ’80s he was building bigger, stranger ensembles — most famously his Sextett — where those ideas could really bloom. Records like When Was That? and Easily Slip Into Another World lay out his knack for unusual instrumentation — tuba, cello, paired horns — that give the music a dense, unpredictable weight. These bands don’t just play his tunes, they inhabit them, navigating charts that feel at once meticulously plotted and wide open. The more he composed, the more obvious his intent: Threadgill wasn’t content to just play jazz. He was out to reinvent how it could move, how it could sound in a room, how it could live.

By the late ’80s, Threadgill was restless for bigger canvases. In 1988 he unveiled the Society Situation Dance Band, a sprawling, joyous ensemble that was less a detour than another bold chapter in his ongoing experiments with scale. The Hamburg concert at Fabrik woven into this post in three parts remains the most vivid document: Threadgill at the center of a stage crowded with saxophones, brass, tuba, cello, accordion, guitars, and layers of percussion. But it wasn’t some throwaway experiment. Like Air in the ’70s or the Sextett earlier in the ’80s, the Dance Band reflected his impulse to rethink what a jazz group could be, only this time with the chaos and jubilation of a street parade crashing through.

The music pulled together the rigor of his Sextett and the playfulness of Air, but blew them out into something unruly and carnivalesque. In many ways, the Society Situation Dance Band set the stage for his 1990s groups — Very Very Circus, Make a Move.

Out of that late-’80s explosion came a new phase, one that pulled Threadgill into the studio alongside bassist and producer Bill Laswell. The two shared a taste for density and for testing how far music could bend without breaking. With Very Very Circus, Threadgill built one of the strangest working bands of the decade: two tubas, two electric guitars, trombone, French horn, and drums. On albums like Too Much Sugar for a Dime (1993) and Makin’ a Move (1995), that unlikely orchestra collided with Laswell’s downtown New York aesthetic — tuba choirs grinding against distorted guitars, odd meters snapping into sudden funk, bursts of improvisation detonating inside heavy, architectural grooves.

What made those records stand out in the 1990s isn’t just their audacity but their clarity. Laswell’s deep, almost physical production give Threadgill’s charts a muscular punch, while Threadgill’s writing keeps the chaos purposeful. The result is music that lurches, stomps, and soars in a single breath. In a decade awash in crossover experiments, few sounded as alive, unpredictable, or flat-out strange as these.

Threadgill’s story doesn’t end with the Laswell years, of course. His catalog stretches well beyond Very Very Circus, into the 2000s and 2010s with groups like Zooid and projects that earned him a Pulitzer and solidified his place as one of America’s most original composers. But that’s for another time. His body of work is far too broad, restless, and surprising to corral in a single post, and I haven’t even begun to explore the last two decades of it. That journey comes next.

Henry Threadgill and Society Situation Dance Band at Fabrik, Hamburg 1988

Band:

Henry Threadgill-conductor

John Stubblefield-tenor & soprano sax

Booker T Williams-tenor sax

Ted Daniel-trumpet

E.J. Allen-trumpet

Craig Harris-trombone

Conrad Herwig-trombone

Leroy Jenkins-violin

Charles Burnham-violin

Terry Jenoure-violin

Bob Stewart-tuba

Diedre Murray-cello

Akua Turre-Dixon-cello

Brandon Ross-guitar

Donald Nicks-el. bass

Reggie Nicholson-drums

Bobby Sanabria-percussion

Drew Richards-vocal

Sherry Scott-vocal