Step into one of the largest and most beloved online record shops in the world… While the defending champion Philadelphia Eagles continue their playoff run to a possible […]

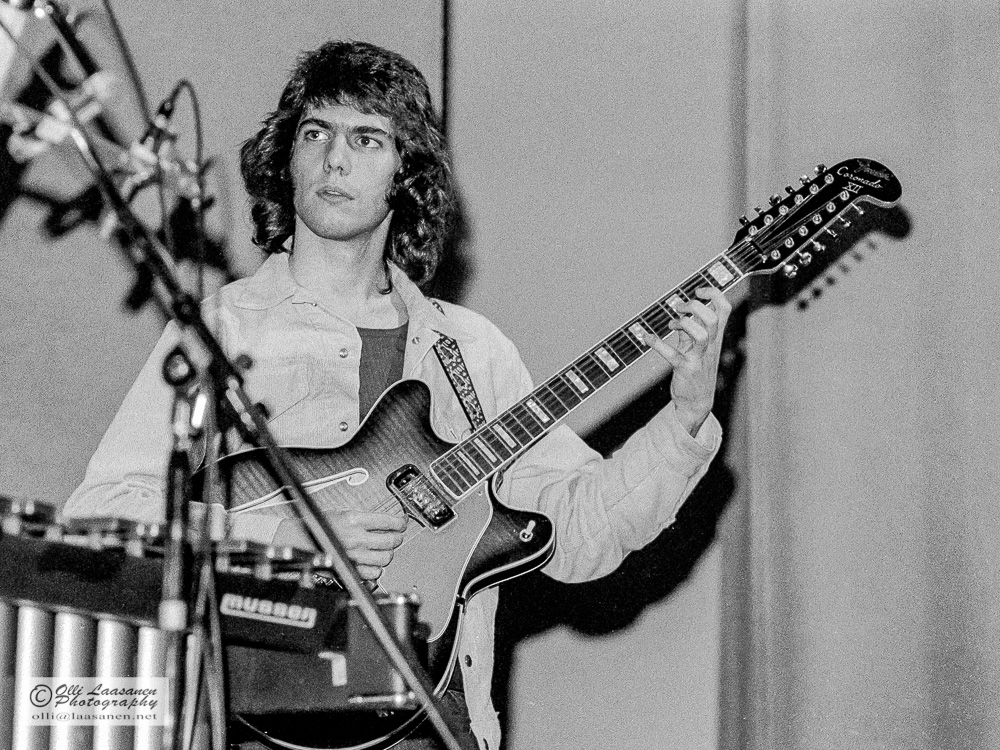

The Pat Metheny Method: Not Fusion, Not Jazz, Not Rock (1979)

Pat Metheny, Lyle Mays, and Danny Gottlieb on ECM, jazz, and performing live. Archived digitally from Musician Magazine.

I first met Pal Metheny a few years ago in Wichita, Kansas while hanging around backstage waiting for a concert to begin. Pat introduced himself and said he was from Lee’s Summit, Missouri. He also said he knew most of my group’s tunes and wanted to sit in … (reaction: is he kidding? This kid who looked about fourteen, all smile, teeth everywhere… there in the middle of Kansas?) Then, he proceeded to say how one of my early records had first influenced him to take up guitar and try jazz music. A great compliment, of course, but I was still skeptical and feeling older by the minute. But after heard him, I had to admit he played pretty damned well; an incredible blend of Missouri, hip, chops, and all those teeth.

— Gary Burton, 1975

Upon first meeting Pat Metheny, the initial tendency is to react much in the manner described by his former leader, Gary Burton. The guitarist is now 24, but in his blue jeans and tennis shoes he could pass for 19 or 20 ( he still gets carded occasionally when he works clubs). He talks about his art with an intense enthusiasm and an idealism lacking in all too many performers — as though he hasn’t yet become completely jaded by the business end of making music. His personality seems best described by adjectives such as candid, energetic, straightforward, unpretentious — qualities also inherent in his music.

It would be wrong, however, to mistake Metheny’s youthful zeal for naivete. Five minutes of conversation with the guitarist / composer/ bandleader is enough to reveal that behind the boyish exterior is a level headed, serious artist, who seems to be handling his sudden popularity with a great deal of maturity. Pat Metheny is 24 going on 45.

Today Metheny heads a quartet — with Lyle Mays on piano, Dan Gottlieb on drums, and Mark Egan on bass; each within a couple of years in age of Pat, who is the youngest — which commands a strong and growing following made up of both jazz and non-jazz fans. The Pat Metheny Group — Metheny’s third album for ECM and the band’s first joint effort — was recorded a year ago January and is, by jazz standards, a runaway hit.

If Metheny’s current status is impressive, his musical background is downright amazing. He grew up in the Midwest, in a small town with a population around 6,000. He first noodled around with a guitar, playing rock and roll, at twelve but doesn’t admit to seriously taking up the instrument until age fourteen, when he became increasingly interested in jazz. Within his first year of concentrated study he was awarded a Down Beat music scholarship, with which he attended the magazine’s summer camps. Shortly after turning eighteen, Pat entered the University of Miami’s music program. ” When I got out of high school,” he recalls, ” I was kind of like the star quarterback — all these schools came around offering me scholarships.” His days as a student ended after only one semester, when he was offered a position on the University’s faculty. (” It was hilarious at the time; my parents were wanting me to get a liberal arts degree so I’d have something to fall back on. In fact, just last Christmas my dad wanted to know when I was going to go back to school.”) After a year in Miami, Metheny began teaching at the Berklee College of Music in Boston and was soon playing electric 6- and 12- string guitars behind one of his early inspirations, Gary Burton, with whom he recorded three albums. ” After I met Gary at that festival in Kansas,” Pat explains, ” we got to be friends and he asked me to come up to Berklee kind of as his assistant. I moved up there hoping that once I got there he’d ask me to join his group — it was kind of my dream — and he did.”

The question that is at this point undoubtedly on the lips of every guitarist ( at least those who on having read this far haven’t retired their axes at the advanced age of 21) is, “How? How can anyone advance that quickly on the guitar?”

According to Metheny, “All I can say is that it came extremely easy for me. I remember when I got this Gibson and decided I was going to learn to play the guitar, within a week I could play almost as fast as I can play now. It was just so easy for me to do. I have a very hard time explaining it; it’s real difficult for me to talk about. The only thing I can figure is that I must have had a great chromosome count for being a musician or something — because there are musicians all over my ancestors. I’ve got an older brother, Mike who’s an excellent trumpet player. He teaches at Berklee; he plays like Art Farmer or Chet Baker. My father played trumpet all through college, and my mom’s father was a professional trumpet player all his life. There was always lots of music around.”

A battery of the country’s top PR men laboring around the clock couldn’t write a better blueprint for the next Guitar Star. Metheny does not seem to be interested. Like the other three-fourths of his quartet, his playing is better called sensible with a minimum of flash. You are impressed more with the tunes in general, and Metheny’s keen sense of melody in particular, than with displays of technique and speed. ” I just see myself as a guy in the band,” stresses the group’s leader. ” I really have no interest in being the next guitar hero, because to me it’s something that changes every year. Also, the nature of the way I play doesn’t ask for that; I’m not really showy like some guys. I’m more interested in establishing an atmosphere to the music, which people can identify with me and the band. And, to be quite honest, I don’t have any fantastic love for the guitar as an instrument. I don’t feel that religious about it. I think it’s nice, it’s okay, and it’s real flexible these days. But, to me, an acoustic piano is the instrument. If I had it to do all over again and I was about three years old, I’d start on piano. I was never attracted to the guitar,

per se. I got braces on my teeth when l was about fourteen, so I couldn’t play the trumpet anymore, and I had a guitar, and I heard Wes Montgomery. A lot of things happened at once. But I don’t really consider myself a guitar player; I consider myself a musician who happens to play guitar. I feel like I’m in the process of defining my music, and I feel so much like a beginner it would be unwise to come on like a Guitar Star. I think I’d be digging my own grave.”

“I’m not sure I’m ready to call what we do jazz knowing Coltrane’s group existed… I see our group as reporters on the times… and a case can be made that that’s what jazz is anyway.”

Pat feels his indifferent attitude toward the instrument he plays is shared by most of his fans. “Most people who like us,” he says, “don’t know anything about the guitar; they like the spirit of the music. We don’t draw that many musicians; they’re more into players who are expanding the vocabulary on a technical level. I think there are a lot of guitar fanatics who can’t understand what all the fuss is about. I know there are. People have come up and told me they can’t believe I’m getting all this attention, because I don’t play as fast as so-and-so. Our stuff is very human music; we’re dealing with more of a ‘life’ approach, as opposed to just more notes, yet another chorus or whatever.”

Metheny’s perception of his audience seemed to be substantiated when he gave a seminar for an audience of all guitar students at the Guitar Institute of Technology ( G.I.T.) in Hollywood last February 14. There were a few of usual hardware questions concerning amps and strings, the sort of stuff guitar freaks are supposed to be interested in (“I go from my guitar into an MXR digital delay set for a little bit of slapback echo, then into an Acoustic 134, from that into another digital delay — a Lexicon with two delay outs; I put one amp on one side of the stage at 19 milliseconds, and another amp on the other side of the stage at 29 milliseconds with a little pitch bend on it, with a voltage controlled oscillator …”). But by far the most questions concerned Pat’s philosophy of music, his sources of inspiration, his influences, what he sees as the purpose behind what he does.

This is important for two reasons: 1) it shows how a fair sampling of other guitar players ( all at a fairly intermediate or advanced level) view Pat Metheny; and 2) it may point to a new trend among young guitarists to not forsake inspiration in favor of mere speed and dexterity. If such a trend materializes it will be due in large part to the impact of players like Metheny.

Pat Metheny is in many ways a fairly unorthodox guitarist just in terms of how he plays the instrument (” there’s all kinds of stuff I do that’s real weird and doesn’t seem to work for other people”), not to mention his extraordinary background and phenomenal rate of development. During his four-hour question- answer session at G.I.T., some members of the student body — many of whom spent a minimum of eight hours a day with a guitar in their hand and their head buried in a book of exercises — were intrigued, if not shocked, by some of Metheny’s “study methods.” For example: “This seems to surprise people, but I never practice. I found that after a certain point it got in the way of improvising, rather than encouraging you to improvise — I found myself playing the same things I was practicing when I was supposed to be soloing.” And when he is soloing, is he thinking of the melody, the tune’s changes, rhythmic motifs? ” I play my best when I don’t think about what we’re doing at all. Sometimes I intentionally distract myself; I’ll notice that the bass drum is about to slide off the rug, or I’ll think about having to do the laundry when I get home. It really works in such a way that your conscious mind is on one level, but the subconscious mind is where all the interesting stuff is — that’s where everything you’ve ever learned or heard is stashed away. So if you let that stuff in back take over, then the real good stuff starts happening.” As for music he enjoys listening to, Metheny included Linda Ronstadt, Nicolette Larson, the Dixie Dregs, and guitarist Neal Schon of Journey, alongside a lengthy list of jazz players encompassing all styles and eras.

It would be impossible for any musician of Pat Metheny’s generation to grow up without absorbing the countless influences readily accessible thanks to mass media. Metheny (who was nine and a half years old when the Beatles first appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964) sees the validity in Jimi Hendrix as well as Stan Getz, and recalls with enthusiasm obscure AM hits from his adolescence such as ” She’s Not There” by the Zombies and ” Dirty Water” by the Standells, in the same way that a musician a couple of generations older might remember buying 78s of Count Basie or Benny Goodman. But the outside ingredients seem to spice up, rather than define, Metheny’s resultant sound, which is more jazz than rock — and, in fact, more jazz than jazz-rock or fusion.

“I’ve always liked lots of different kinds of music,” he muses, “not necessarily just jazz. In fact, much of the jazz I hear really bores me. I love the highest level of playing — like Miles or Coltrane or Sonny Rollins or Keith Jarrett — but the sort of mediocre players you don’t hear so much about, I can tell when I hear them why no one talks about them. But I’ve always kept right on top of what was happening with Top 40 and all that. I’m a big fan of that sort of stuff, and I like country music, too.

“Speaking just in terms of my enjoyment rather than influences, there’s a guy named Steve Morse with a band called Dixie Dregs. They’re incredible; it’s like a cross between the Allman Brothers and Stravinsky [laughs]. Steve’s also one of the best classical guitar players. He can play the most delicate acoustic stuff on the one hand, or incredible sort of Roy Buchanan style Telecaster — but nothing in between. There’s a guy in New York named Michael Gregory Jackson, who plays with the so-called avant-garde community, and I think he’s amazing. Totally unusual intervals, strange stuff. And I like Alan Holdsworth. Of the current young guitar players, those are the three guys that I point to as my peers, who I listen to. I think Keith Jarrett is probably the greatest musician of our time.

“But I never let myself forget the historical perspective on things — that Lester Young did exist. And even though most people haven’t heard of Lester Young, a lot of the music that’s popular today can be traced back directly to that source — certainly elements of my playing can be. Of course, I like all the jazz guitarists, too. I’m still really knocked out whenever I hear Jim Hall or Wes Montgomery, also George Benson and Pat Martino. Mick Goodrick is a true great, probably the loosest improviser I’ve ever heard. Joe Diorio is someone I have a real high regard for. Attila Zoller is a good friend of mine. When I was sixteen, I went to New York and stayed with him for awhile, and we went to see Jim Hall every night. That’s actually where I made the decision to do this whole thing.”

Besides the players whose records Metheny was collecting, one significant source of inspiration came from a local unknown right in Kansas City. Pat reminisces: ” At one point, when I was maybe sixteen years old, I was thinking, ‘Boy, I’m getting really good!’ Then I heard a guy who just killed me, a saxophone player. Herman Bell was his name. He’s an older black guy who works at the post office in Kansas City, and he played with Charlie Parker and all that. He was one of those guys who could play through a tune like ‘ Donna Lee’ for four hours and never repeat himself. Ever since that time I’ve never thought that I was that great. And I’m sure he wasn’t that good if I were to judge him by my standards now, but I have this image in the back of my mind of what that guy sounded like, and the sort of looseness and freedom he had. That’s going to stick with me probably till the day I die — that feeling of amazement.”

Part of the reason for Metheny’s success as an instrumentalist is that he has always had incredibly high standards set for him, both by himself and by those he’s played with. “I’ve been playing with great players from the time I was fifteen,” he states, ” and until this group, I was always the worst guy in the band, which is the very best place to be to learn how to play. When I was eighteen I was standing next to Steve Swallow and Bob Moses [ with Gary Burton], cats who’d been playing twenty years. You can’t beat that. You can’t beat getting blown off the bandstand; nothing will make you get better quicker. That aspect more than anything just put me in a place where I had to get better. Also, I had no one to compare myself to, as far as peers who were also playing guitar in the style I was playing. So in everything I did, I compared myself to the greatest players — you know, Wes Montgomery and Jim Hall. I’d play something that was probably real good for someone my age, but didn’t even consider that fact, because the standard was obviously Wes Montgomery, and in comparison to that I wasn’t that great.”

“To me, making records is a means to get in front of people and play for them live…as opposed to the introverted jazz image.”

Besides no doubt increasing his facility on, and his knowledge of, the guitar, this awareness of the real jazz virtuosos and his relation to them helped form Metheny’s personal voice on the instrument. He explains: ” I saw the entire guitar spectrum — like Jimi Hendrix to Jim Hall or whoever — and saw these huge gaps in different places where I could really imagine myself fitting in. And I saw this big gap between Jim Hall and John McLaughlin … just waiting. Somebody that plays melodies and non- rock, kind of fuzz sound, but at the same time had knowledge of bebop and changes and could play that stuff too but never really did. I noticed that when I was about sixteen or seventeen years old, and I just sort of aimed for that little hole ever since. And, to me, there are still some gigantic gaps in the guitar spectrum.” Probably the most identifying characteristic of Metheny’s lyrical style is his knack for simplicity. ” I’d say Jim Hall was a good source for the simplicity That whole school — Jim Hall, Bill Evans, Art Farmer, Steve Swallow, Stan Getz, Chet Baker — the early 60s kind of cool school. I really love simple melodies and simple songs — like folk music and country music — and I try to capture that essence as much as possible.”

The folk/country element Metheny refers to, the midwestern side of his paying and composing, is clearly evident in all of his work but is more apparent on Bright Size Life (recorded in late 1975) and Watercolors (from early ‘ 77) than on the Pat Metheny Group. The scenes and images Metheny was writing about are best reflected in titles such as “Omaha Celebration” and ‘ Unity Village” ( from Bright Size Life), “Oasis” and ” Lakes” ( from Watercolors), and “Midwestern Nights Dream” ( on Bright Size Life as well as Gary Burton’s Passengers LP). The style is best described by the title of another tune on Bright Size Life, “Missouri Urcompromised.” Probably the best example of Pat’s country approach is the title cut of his new solo album, New Chautauqua. “On all the tunes on this record,” the composer explains, ” I thought about nothing but when I was growing up, what it was like. This music is about that. Chautauqua was a term for a bunch of guys who traveled around in Missouri during the 1850s and played dances in Oklahoma and Texas.They were musicians who did one-nighters, and my great grandfather was in that. This record was a special project, and I don’t expect it to sell more than about ten or fifteen thousand copies. But it doesn’t matter to me, because it’s a statement that I really wanted to make. To me, there’s an almost political feel in that tune [“New Chautauqua”]. It’s real country, but at the same time the playing is coming from a Lester Young thing.”

“I really like ECM. There’s a kind of atmosphere where the number one priority is to play your music, while on most major American labels the priority is to sell some records.”

On the group album, Metheny’s beautifully melodic concepts are teamed with the crisp, uncluttered texturings of pianist Lyle Mays. Side one is comprised of two Metheny / Mays collaborations, “San Lorenzo” and “Phase Dance,” which are undoubtedly the group’s most popular pieces. Metheny describes the atmosphere in which the two partners write as ” more like an encounter session. We sit down with a guitar and piano and play eight or ten hours, sometimes just on 16 bars, to really nail it. Then we work out voicings and the complicated stuff. But it’s never the same way twice Sometimes I’ll walk down the street, and I’ll hear a tune in its entire, completed version, and that’s that. I’ll just go home and write it down. And I never write on the guitar; I always hear it in my head and then write it down.”

Mays adds, “On the early tunes that we wrote together it was much more Pat’s show. He would have most of the ideas and the concept for the tune, and I would add maybe some new melodic material. The newer stuff has really branched out a lot, where we’ll get into actually both sitting down together and writing the stuff out right there. It’s not like one person will come in with the idea and the other person goes home and works it out. We’ll just sit down at the piano, and he’ll get his guitar out — like you’d imagine two people would write songs together. Pat’s really got that melodic stuff together. I’ve learned an awful lot from Pat about melodic theory. You can’t really put it into words; it’s just something he does. You can hear it, and you can learn from it.”

With the success of the group album, not to mention the superior talents of all four members, it would seem inevitable that ECM would follow its pattern of turning sidemen into leaders, at least for recording purposes. There is already talk of Lyle Mays cutting a solo effort. Like Metheny, Mays comes from a small town in the Midwest, Wausaukee, Wisconsin. “I first heard about Lyle,” Metheny recalls, “when I was maybe sixteen or seventeen years old. A friend of mind named Dan Haerle, who’s kind of a famous jazz educator, told me about this incredible young piano player, and he also told Lyle about this guitar player down in Missouri. We even talked on the phone around that time about possibly getting together. I finally got a chance to hear him play at a jazz festival in Wichita — ironically, the same festival I’d met Gary at two years earlier — and he just knocked me out. I was extremely impressed with his playing and his whole vibe as a performer. So we spoke, and I had him come up to Boston to do a few gigs, and we worked real well together. I was just getting set to do Watercolors about that time, so I had Lyle play on it. When it came time to leave Gary’s band, he was the first guy I contacted — so that was the nucleus of the group.”

The other two-fourths of the quartet, Dan Gottlieb and Mark Egan, were both musicians Pat had known from his tenure at University of Miami. The list of musicians who were students at Miami the year Metheny taught there, 1972, is truly amazing. “It’s miraculous how many people were there who are now musicians,” exclaims Metheny. “We’re all still sort of dumbfounded that things have turned out the way they have, because when we were all there we were just a bunch of guys goofing around. I’m talking about Danny and Mark; Jaco Pastorious; Mark Colby, who’s got a record out on Bob James’ label; all of the Dixie Dregs; Eric Traub, who’s a tenor soloist with Maynard Ferguson; Narada Michael Walden; Ross Traut, and excellent guitar player living in New York; Hiram Bullock, who’s the number one studio guitarist in New York now; Cliff Carter, who’s maybe the number two or three call pianist for studio stuff in New York; Stan Samole, who’s done a lot of Don Cherry records — the list goes on and on. At the time it was looking like the University of Miami was going to be the hip jazz school. But when we all left the thing kind of petered out.”

During his stint there not all of the gigs were exactly hip jazz. “I did a lot of dumb gigs in Miami,” he concedes, ” playing for Tom Jones, Ann- Margaret, Pearl Bailey — you know, really awful stuff. Jaco and Danny and I played a week with this girl Lorna Luft, Judy Garland’s daughter. We took it so far out that girl’s never going to be the same[laughs]. If she only knew what was going on underneath, she would have died.”

Drummer Dan Gottlieb recalls that period: ” I met Pat in ‘ 72 and played with him all the time at the University. I’d say I’ve played with Pat more than any other musicians. We used to sneak into the practice rooms at two in the morning when no one was around and play space sessions until eight, and then cut out on our theory courses [laughs]. Later, I’d fly up to Boston just to play with him.”

Pat picks up: “Danny and I were always very close. We did duo concerts down in Miami, and I loved the way he played because it was so completely different than anyone I’d played with before. He wasn’t really a great jazz drummer, and he wasn’t really a great rock drummer. He was in this sort of in between thing, very similar to my situation as a guitar player. We seemed to have a nice rapport. In fact, I got Dan the gig with Gary Burton when Bob Moses left the group. But Gary runs a band in such a way that everybody has to answer to him for every note they play from the start of the night till the end of the night. Which is cool, you know, and I appreciate that approach, and it works real well for Gary. But the problem is that Danny’s playing is based on a sort of strange chaos where anything can happen at any time. As a result of that, any time Danny would go off on one of his tangents, Gary would, like, yell at him or something, and that would inhibit Danny. When he got inhibited the music would tend to lose the spirit that he was capable of generating. So it didn’t really work out too well for Danny or for Gary. When I decided to leave Gary, I asked Dan if he’d come along. So that was three- fourths of the group.”

As with all albums on Manfred Eicher’s ECM label, The Pat Metheny Group was recorded very quickly; the actual sessions took only two and a half days, and the mixing took one day. New Chautauqua was done in two days, with Metheny overdubbing several guitars and bass. “Manfred believes very much in getting the moment on tape,” says Metheny, “and that makes so much sense. He creates an atmosphere of incredible intensity and concentration that’s hard to work under but works extremely well. He really makes you focus on the moment, and he bats a thousand at capturing the essence of a date. You can feel what it’s like to be at that date whenever you listen to those records. That’s really what counts; people seem to respond to that. I really like ECM. I like the sort of low-key format and the lack of hype or whatever. It’s just guys playing their music, and that’s the kind of setting I prefer to be in — especially at the age I’m at, where I feel like it’s just barely starting to come together. After my first record came out I got besieged with offers from all of the so-called major labels, but I really like ECM. There’s a kind of atmosphere where the number one priority is to play your music, while on most major American labels the priority is to sell some records.”

Metheny and company take sort of a reverse route from most artists in preparation to recording an album. Explains Pat, “We go on the road for months and months at a time; I’m a big advocate of letting the tunes develop and then recording them. We write the music, play it for about six months, then record it. See, even though we’re recording the stuff live, we have an advantage because we’ve played the tunes for months, so we rarely make goofs.” On the relative merits of the Eicher two-day method of making an album, Lyle Mays feels, “You’re able to focus your energies and thoughts, and there’s an awful lot to be said for that. We just did a film score for a series of short documentaries called Search For Solutions, and we had unlimited time in the studio, But it was kind of a mixed blessing.”

Contrary to most bands who take to the road mainly for the purpose of selling their records, Metheny to enable him to tour. “To me, there’s nothing like the feeling of playing before a live audience, with that energy and intensity there. That’s why I do it. If I did nothing but make records I’d be bored to death. To me, making records is a means to get in front of people and play for them live. I’ve always been interested in playing for people, as opposed to the introverted jazz images. I’ve always been one to send it out. The nature of our music is pretty outgoing, so our performances are much closer to a rock kind of thing than jazz. The presentation of it is fun for people who aren’t jazz fans as well as for those who are.”

Even though his albums are done very spontaneously, live in the studio, Pat is still interested in the possibility of a live album, because, in his words, “It would definitely capture an element of the band that I don’t think we can get in the studio — which is our sort of kick- ass side.”

What comes across on record is mainly the material, the tunes and how well they are executed. Onstage, what is most impressive is the band’s power and the sort of tun atmosphere they establish with an audience. When the band played San Francisco last February, they proved that even serious, accomplished virtuosos can still laugh at themselves and have fun with the music. The quartet played two two-and-a-half-hour sets which included several favorites from Metheny’s three albums and a large body of material not yet on record. The evening’s highlight, however, was Metheny’s spontaneous tribute to the 60s. Starting with a feverish guitar-drum duo called “Mean Time,” Pat worked his way into an uptempo 12- bar shuffle with the rest of the rhythm section joining in. From there he segued into “Louie Louie,” into the Animals’ “House Of The Rising Sun” ( With Mays playing Alan Price’s organ part on synthesizer), into possibly the hottest rendition of “Wipe Out” ever, then out with a slow blues. In each segment all four members played with as much dedication and enthusiasm as they had during the set of original compositions. This was by no means a bunch of jazz snobs making fun of rock and roll; this was a garage band — an unbelievably talented one — playing as though their lives depended on every note. When the commotion died down, Metheny sidled sheepishly to the microphone. “You people have to promise not to tell anybody about that,” he told the sell-out crowd; “it could ruin our reputation.”

“We’re all young, and for better or worse, that’s the way we play. Some people would call it immature, some would call it fresh. We take chances a lot, because we’re not into any ruts. We don’t really know what works yet.”

Those purists who choose to categorize styles of music may be correct in calling Metheny’s approach something other than jazz, but it seems obvious that Metheny’s loyal and growing audience couldn’t care less about such distinctions. Pat Metheny may not be able to blow through bebop changes with quite the facility of a seasoned veteran like Joe Pass, but the original voice he has found as a guitarist by far outweighs any shortcomings of technique ( besides, how many “seasoned veterans” can really do justice to ” Louie Louie”?).

And as Metheny points out, ” The question is, what is jazz? The question I’m asked six or seven times a day in interviews is, am I a jazz musician 2 or, are we a jazz group? I’m not so sure I’m ready to call someone like Chuck Mangione jazz, and I’m not sure I’m ready to call what we do jazz. knowing that Coltrane’s group existed. I don’t see us playing that kind of music at that kind of level. But I do see our group as serving a function as reporters on the times, on what’s going on right now. I think we reflect sort of a spirit of this branch of our generation. And a case could be made that that’s what jazz is and always has been. There’s an element of capturing the mood of a time.”

Metheny’s major concern at present is establishing his quartet as an identifiable group, with stable personnel. “Bands used to be real strong personalities,” he stresses,” like Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers or Miles’ band — instead of a star with a backup group. And other than Weather Report and Oregon, we’re about the only guys where you know who you’re going to see in the band from one time to the next. I think the other members of the ensemble need to be featured much clearer in a lot of groups; otherwise it almost turns into Musak. Not that I have anything against him, but, like, Steve Gadd is or every record that comes out and after a while there’s nothing special about it.”

Part of what gives the Pat Metheny Group its distinctive sound is that, although the instrumentation is tairly standard — guitar, piano, bass, drums — each member plays a role not ordinarily associated with his instrument. Naturally, the guitar often plays the melody, the piano provides a bed of chords, the bass holds down the bottom, and the drums act as sort of a kinetic catalyst; but the roles shift just enough so that. if you didn’t already know, it would be difficult at times to tell just who is the band’s leader. Much of the time it seems that the drums are what dictates the music’s reaction — and that is actually quite often the case.

“The way Danny plays with the group,” Metheny feels, ” is maybe the second most important factor in our sound. Most of the discussion when we write a new tune is, What are the drums going to do?’ What they have to do is capture the essence of the groove, but at the same time be loose and a free spirit throughout the music. That’s what really gives the piece its character, our sound. With most groups and records I hear today the drum part may as well be a machine — totally metronomic. They lay down the drum track, and then they put everything else on top of that. And I have no interest in that; to me, that’s so boring I’m much more interested in the kind of playing that stems from, say, Elvin Jones or Jack DeJohnette, the drums are making a constant commentary on the music, and it’s like a dialogue with the music itself.”

Gottlieb reiterates, “The thing with Pat is that we’ll sometimes come up with something that could fall into a certain category, and if I play it the way a typical drummer would play it, Pat will say, ‘ Try something different.’ So it’s hard for me, but it’s something I really enjoy doing, trying to turn it around and come up with a sort of an all-purpose style. For some reason I never worked out that many drum licks, like a lot of drummers will do, and Pat really has no use for drum licks. That’s why I play a lot of cymbals, because to me that’s the most musical thing that fits. And I’ll just open up sometimes and see where it goes. I’m still at the point where sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t.”

In Mays’ words, “We’re all young, and for better or worse, that’s the way we play. Some people would call it immature, some would call it fresh. We take chances a lot, because we’re not into any ruts. We don’t really know what works yet. And I think we all have found new ways of approaching everything. The concept of the group demands that.”

The Pat Metheny Group will be back in the studio in July to cut their next group album, to supposedly be released by the end of September. And, although other recording projects will be forthcoming ( Metheny is currently interested in recording another album with Jaco Pastorius), it seems as though Metheny, Mays, Gottlieb, and Egan plan on sticking together for a long time to come. “I expect it to stay together for quite a while,” the leader says hopefully, ” as long as I can keep it. It’s a very nice balance of personalities, and we’ve been watching each other grow a lot musically. We seem to stimulate each other’s growth, which I think is real important. But I am very much into having a band, as opposed to being Pat Metheny with whoever he can get to go out on the road — which is the way most people do it now.”

Lyle Mays agrees: “This is definitely a group, and there’s a lot of mutual respect — there has to be to play together. It’s taken two years to get the music to this point with these same people, and it’ll be hard to get it back just starting from scratch. I’d be a fool to leave. I don’t know how the others guys feel, but there’s nothing else out there as far as I’m concerned; this group is it, it’s happening. And even if I wasn’t in this group Pat would be my favorite guitarist.”

This article was originally published in 1979 for Musician Magazine and has been posted here digitally for archival purposes. Check a scan of the entire publication here.