A candid 1996 interview from Jockey Slut captures Andrew Weatherall at a moment of recalibration, reflecting on Sabres of Paradise, remix culture, DJ life, Two Lone Swordsmen and his deliberate […]

Listening to the Light: Harold Budd in His Own Words

In this 1994 interview, the late composer reflects on beauty, intuition, and the quiet defiance that shaped his path from army-band novice to accidental minimalist.

The late Harold Budd never behaved like a composer chasing the next revolution. His music — and the way he talked about it — suggests something slower, more interior, as if the work begins only once the noise of ambition fades. In the below conversation from American Originals: Interviews with 25 Contemporary Composers, Budd traces a crooked path from army-band novice to accidental minimalist, revealing how intuition and circumstance shaped a sound that would come to define a whole corner of ambient music.

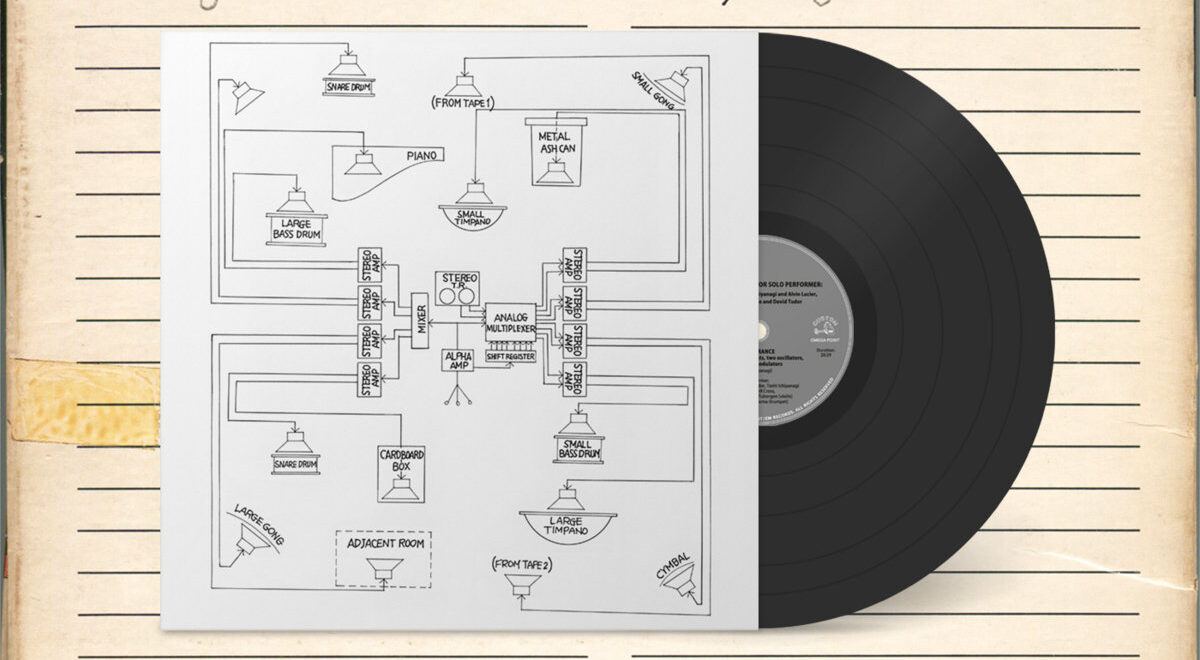

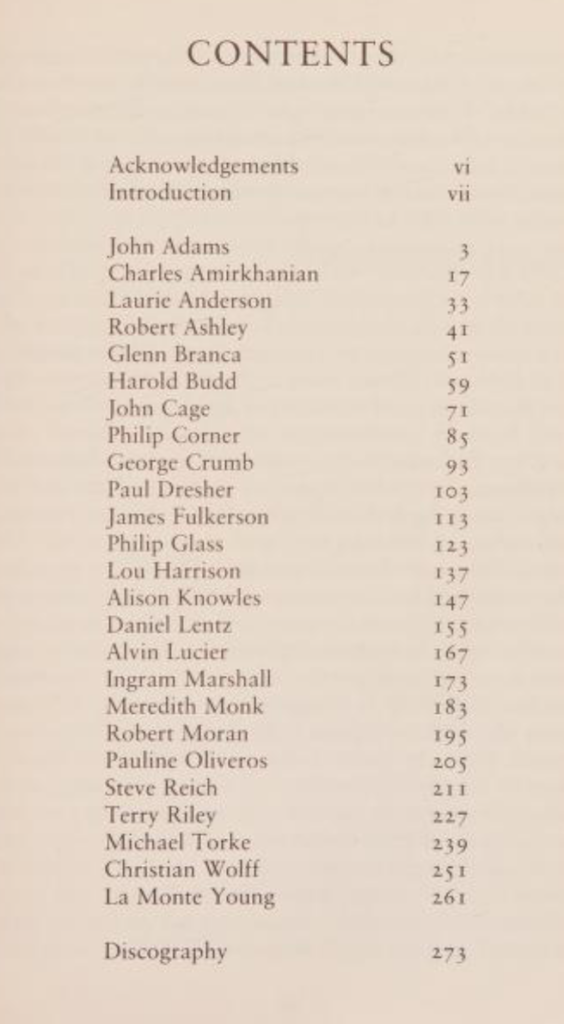

Published in 1994 by Geoff Smith and Nicola Walker Smith, American Originals gathers a chorus of iconoclasts who reshaped the landscape of late twentieth-century composition: Meredith Monk, Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, Laurie Anderson, Glenn Branca, Alvin Lucier, Philip Glass, John Cage, and others. What unites them isn’t a shared aesthetic but a shared independence, a sense that American experimental music had outgrown its need for rules.

But the creators included weren’t without their inspirations, stress the authors in the book’s introduction. “It is interesting to note that almost all of the composers we spoke to expressed some debt to Cage — not as an originator of compositional techniques they might develop, but as a permission giver, an inspirational catalyst who disarmed the very system that might have stifled them. As one young downtown composer told us, the question is no longer ‘Can we do it?’ but ‘What shall we do?’”

The intro continued, “The result of this shift is an overwhelming plurality of styles. Though the spirit that motivates them may be a common one, many of the composers in this collection — from Budd to Branca, from Monk to Moran — are stylistically worlds apart. Nor are there any true ‘schools of thought,’ only individuals.”

Below, Budd’s interview from the book. The entire book is available through Archives.org.

Can you tell us something about your early compositional environment and how it shaped your work?

I was raised in a family that wasn’t particularly musical or artistic, except for my mother, who played harmonium in Christmas carols, Protestant hymns, and sentimental Victorian songs. Those are my earliest memories of hearing anything that moved me. I used to love parades, especially the Scots drummers marching in cadence. That ritualized rhythm absolutely pole-axed me. Every kid loves that sort of thing, but I was transfixed.

How did you come to new music?

When I was a teenager I discovered bebop. My friends and I were such snobs that we wouldn’t acknowledge any other kind of music, especially Elvis Presley. We were totally committed to Lennie Tristano, Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk. It wasn’t much of a leap from there to new music — just discovery and guidance. I didn’t start my formal education until I was 22, mostly because I didn’t want to get a job. I’d worked maintenance for years and saw school as an escape. I had one harmony and counterpoint teacher who turned me on to everything. It gave me a way out of poverty, a path toward a life that felt meaningful.

Most of my friends were filmmakers, painters, proto-architects. Their world looked infinitely more glamorous than composing for an orchestra. I almost wanted to be a painter, but I wasn’t quite the Bohemian. I wanted something a little more staid.

When did composing become a serious option for you?

Right away. The minute I learned which direction the stems went, I started putting things together. I had no skill as a musician and still don’t. It was all imagination. Being forced into an unorthodox method helped me enormously.

Would your music be different if you were a more virtuosic performer?

I’d take advantage of it, sure. But since I’ll never have that skill, it doesn’t pose a threat. If you heard me play, you’d understand there’s absolutely no danger.

What sort of music did you compose initially?

In my first couple of years the free jazz movement started. I thought it would change everything. I heard Don Cherry and was exhilarated, but Paul Bley’s structured approach appealed to me even more. I could keep analyzing Stravinsky and Milhaud without conflict. I also loved Delius, Hovhaness, Roy Harris — artists of great lyricism and individuality. I picked all that up in my first two years of school.

When did you begin to shape your own musical voice?

After two years in the army. I was in the army band, surrounded by professional musicians, learning from them constantly. I began conducting for a weekly radio program in Monterey, which improved my score reading. When I got out, I went to a local university led by Gerald Strang, who had worked with Harry Partch, John Cage, Lou Harrison, and Henry Cowell. Cage came to lecture that first semester, right as Silence was published. Strang was later fired for bringing him, which infuriated me and cemented my devotion to new music. That moment sealed my fate.

So out went the hopes for a sensible day job?

Precisely.

Can you describe the music you were writing then?

Experimental. I’d heard Morton Feldman did graph pieces, so I made my own using colored pencils. A pianist friend played them, and I thought, “This is great—you don’t have to write notes.” Cage and Feldman were my guiding lights then.

Was that an East Coast influence, or did it have a West Coast flavor?

Definitely West Coast. People there were far from Europe, steeped instead in Spanish colonial roots and Asian philosophy — a kind of Bohemian Zen. Lou Harrison once said West Coast music wasn’t afraid to be pretty. That’s absolutely correct.

What does “pretty” mean in that context?

It overrides structure or theory. Whether it’s profound is another matter, but if you’ve made something genuinely, immediately beautiful, that’s enough. I’ll have fulfilled my promise to myself.

Many young composers cite you as an influence. How do you feel about that?

Flattered and slightly embarrassed. It’s a double-edged sword. All that “Harold Budd stuff,” you know? My fault.

How would you describe your music? Is it a branch of minimalism?

It comes from that sensibility, but not Reich’s kind. I saw minimalism first as an art term from West Coast painters—the Finish-Fetish school—whose work I knew well. Pauline Oliveros inspired my exploration of drone music. It didn’t come from La Monte Young at all.

How did you relate to the European avant-garde?

I was aware of everything. Stockhausen fascinated me; Boulez didn’t. Nono’s music was sublimely wonderful. But professors pushed you to “get with it,” which I resented. Cage’s approach blew all that apart. He and Feldman were the true avant-garde, but not the kind fit for schools. Boulez and company? The enemy, then and now.

You can hear traffic, buses, motorcycles. We kept those sounds because they belonged to the performance. Only audiophile maniacs complain, and they’re not interesting people anyway.

Harold Budd

Do painting and painters still influence you?

Constantly. I’m jealous of painters — they finish something tangible. Composers rarely have that satisfaction. Albums come close.

Do you enjoy performing live?

I do it, but it’s not my strength. When the audience is really with me, it’s wonderful. Otherwise, I think, “Never again.” I’m there to meet people, not to put on a show. I tell everyone that upfront.

How do you make your pieces?

It’s a mystery to me. I prepare as much as possible — it’s expensive to work in studios. My recent albums have been acoustic, minimal studio trickery. You can hear traffic, buses, motorcycles. We kept those sounds because they belonged to the performance. Only audiophile maniacs complain, and they’re not interesting people anyway.

Tell us about the Orange Ranch Archives.

They’re old outtakes from a shed on an orange ranch in Fillmore, California, from 1981 to 1983. Lo-fi, magical sketches. We never thought anyone would hear them, which gave them freedom.

What sort of equipment do you use?

I treat the studio like an assemblage artist treats found objects. I used an Indian tom-tom, an electric autoharp meant for schoolteachers. Press a chord button, and it sings. Cheap, but lovely.

Do you process those sounds?

No. I’ve done that before, but it’s become a cliché. At least my records are dated, so people can see I did it a decade before everyone else.

When you recorded The White Arcades, what did you bring to the studio?

Just a list of titles. The Cocteau Twins booked me two weeks at a studio in Edinburgh—wonderful people, good food, one pub in the village. My philosophy: if you’re surrounded by people who love what you do and you can’t make an album, you’re in the wrong profession. I began with a piano loop that wasn’t a loop at all, just imperfect playing that created something new when layered.

Your titles are very evocative. Do they come first?

Often. I carry them like baggage. Sometimes I can’t wait to write something just to free myself of a title that’s been haunting me.

How do you know when a title fits?

I just know. It’s instinct.

What draws you to collaboration?

Curiosity. I want to make something neither side could create alone. I never work with people who read music—it keeps things open and alive.

How did your collaboration with the Cocteau Twins happen?

Simon Raymonde called asking about a piano part from an old piece Brian Eno and I did. Then Robin Guthrie invited me to Scotland to work together. I didn’t know their music well, but I liked it once I did. The result was puzzling in places but worth it. Art without risk isn’t art.

You seem to have one foot in pop and one in art music.

Maybe, though I don’t belong comfortably in pop. I’m more a voyeur. Once you make records, the work isn’t yours anymore—people decide who you are.

Yet you’ve reached a large audience for an art composer.

I like finding out who those people are. I’ve worked with Bill Nelson, for example—an intelligent artist who can talk about sculpture, literature, pop, and arcane art all at once. I gravitate toward people like that. The results aren’t always commercial, but they’re aesthetically satisfying, which is far more important.