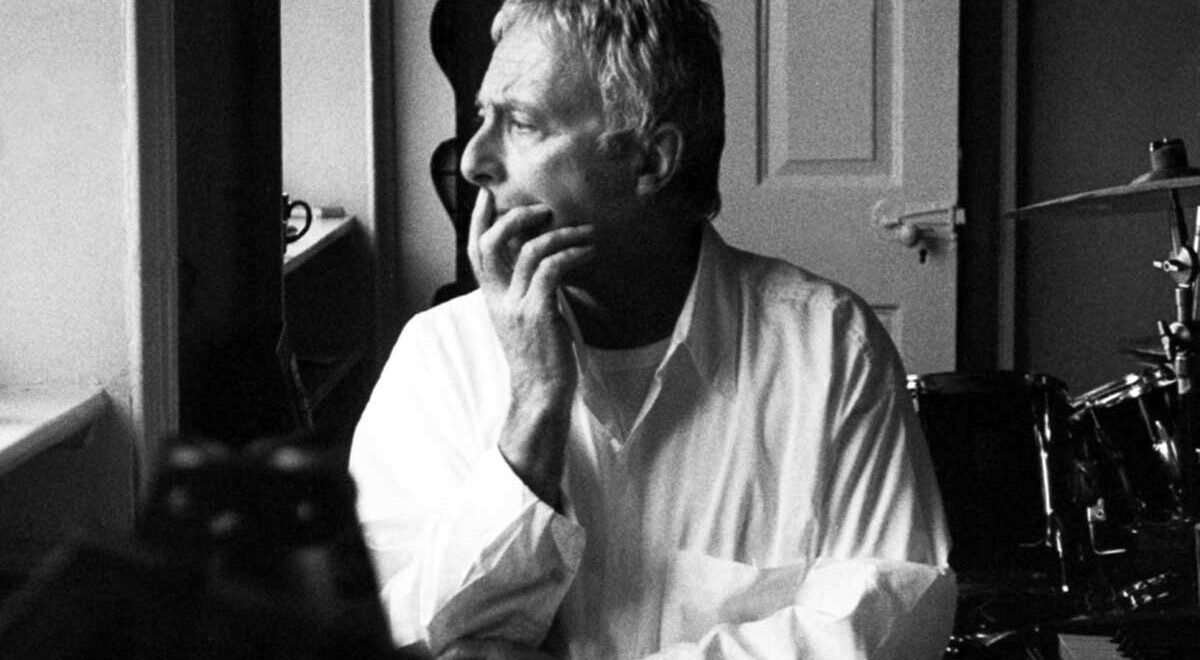

In this 1994 interview, the late composer reflects on beauty, intuition, and the quiet defiance that shaped his path from army-band novice to accidental minimalist. The late Harold […]

The Black Dog and Ken Downie, Pioneers of Warp-Era Electronic Sound

The producer, who died Saturday, helped turn early Warp Records into a laboratory for thinking techno, shaping the Black Dog into one of British dance music’s most restless and enduring voices.

Back in the late 1980s, British dance music was still a loose network of pirate radio signals, dub-plate shops and bedroom studios trying to decode what Chicago and Detroit had set loose. In Sheffield, Ken Downie, Ed Handley and Andy Turner came together as the Black Dog, less interested in rave euphoria than in what those new machines were doing to time, sound and the creative impulse. Their early tracks sounded like transmissions from a parallel UK, one where house and/or techno was not just for the warehouse floor but a language for thinking about the future itself.

Over the weekend, word spread that Ken Downie had died, a quiet shock that rippled through the same underground networks that once carried his music. Messages from friends, collaborators and listeners began to stack up online, all circling the same sense of loss, not just for a producer but for a way of thinking about electronic music that was restless, searching and stubbornly personal. No details have been made public, which somehow feels fitting for a figure who always preferred to let the work speak first, but his absence has already landed with the weight of an era closing.

The Black Dog’s recorded story starts early and moves fast. The first EPs, Virtual and Age of Slack, arrived in 1989 and already showed the group balancing heady design with club pulse. That led to Bytes in 1991, their breakthrough album and a cornerstone of Warp’s early identity. The original trio followed it with Temple of Transparent Balls and Spanners, both classics, before Turner and Handley left in 1995 to form Plaid. Downie kept the Black Dog name alive, pushing it through Music for Adverts and into the darker, more politicized run that included Silenced, Radio Scarecrow, Further Vexations and Music for Real Airports, records that treated late-capitalist Britain as both subject and texture.

Downie had no use for making inaccessible music, so melody and hooks kept creeping in, sometimes almost against the grain of the machinery. Even at their most abstract, Black Dog tracks reached for something you could hold onto, a bass line that lingered, a phrase that looped just long enough to become familiar. That balance between density and invitation was part of what made Downie’s work endure, music that asked for your attention but never punished you for giving it. He also loved to share stuff he loved. His long-running Radio Dogma mix series is accessible via Mixcloud, as is his stellar Dark Wave series of mixes and the occasional live recording.

Downie was never shy about how closely the work was tied to his mental health. “Making music is just battling with depression and mood really,” he said in a 2005 interview. “If you’re down, you don’t really want to do anything.” That tension between paralysis and compulsion runs straight through the Black Dog catalogue, in the way tracks push forward while also folding inward, rhythms tightening and slipping as if mirroring a mind trying to stay in motion.

That made his complicated relationship with the past easier to understand. When early Black Dog material was finally being reissued years later, he admitted, “I hate looking backwards — releasing stuff from 20 years ago wasn’t high on the agenda, he said in an undated interview from the 2000s. But now it’s done and I can hear how crisp and lovely it’s sounding.” Still, nostalgia was never the point for him. The music existed to keep moving, to keep making sense of the present, even when that present was heavy and resistant.