In conversation with Small Medium Large, a new quintet from the burgeoning new West Coast jazz & improvised music scene. In 2018, LA-based jazz and post-rock guitarist Jeff […]

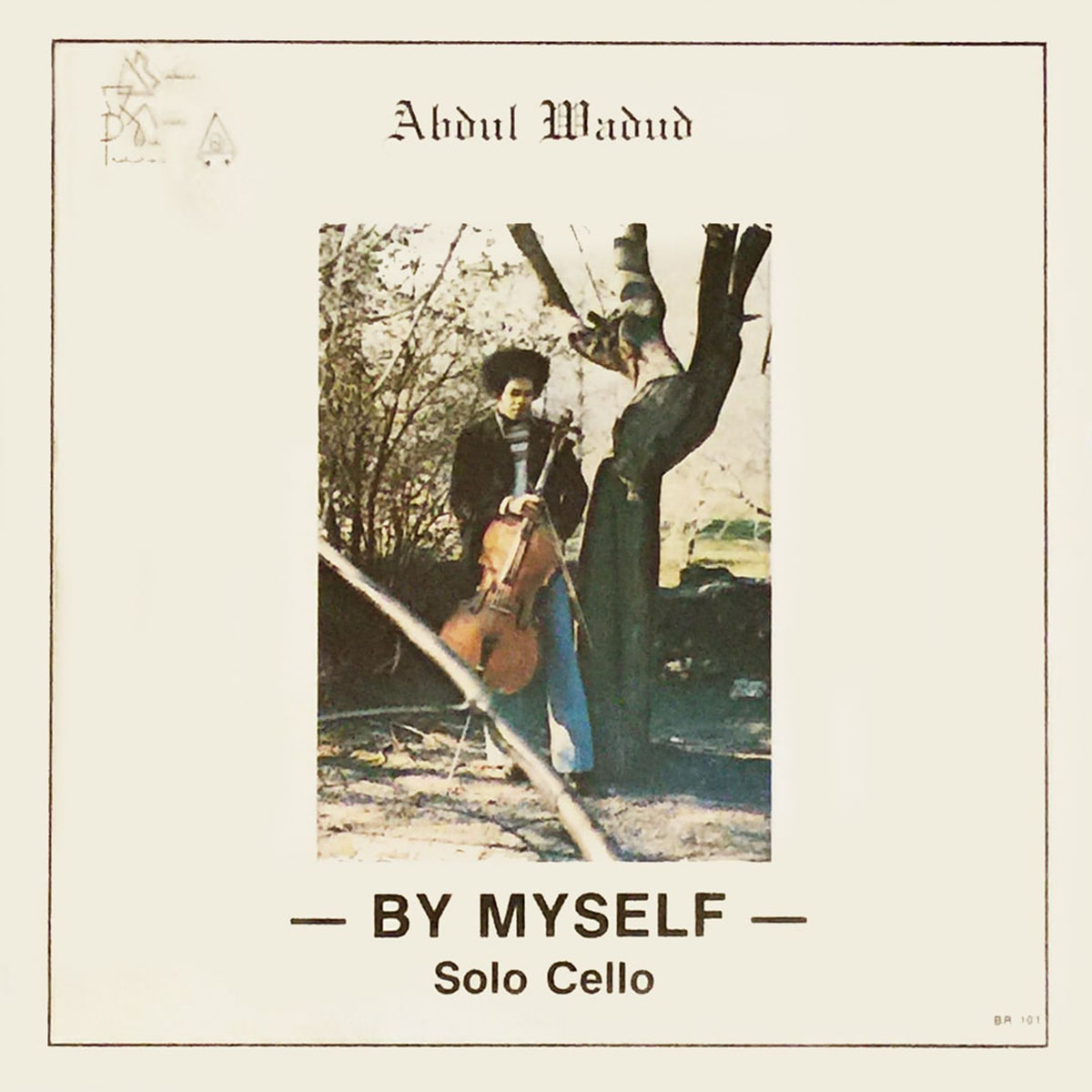

The return of Abdul Wadud’s hypnotic 1978 private press cello album ‘By Myself’

The long out-of-print holy grail private press album is finally being reissued on vinyl.

One of the best parts of being a music freak is having your brain chemistry forever altered through a kind of sorcery on a regular basis: rewired through sounds generated by brilliant strangers who at some point stood in a recording studio, lost in music, and created singular sound waves. Carved into vinyl for posterity, these secret codes lie dormant, waiting for a needle to reanimate them. Once reawakened, they fly through the air and into the ear canals and infiltrate the brain, where the waves work their magic on the psyche.

Have you heard By Myself, the 1978 solo cello album by Abdul Wadud? If so, you’ll be thrilled to know that the Clevelander’s remarkable private press meditation is getting a much deserved reissue. The kind of record that will hush a crowded room and quiet the chatter overwhelming your inner thoughts, By Myself has been remastered from the original tape for vinyl reissue by Gotta Groove Records.

“There really is no easily comparable album in existence,” Gotta Groove accurately notes on its release page. “Abdul Wadud used the cello to make music in a way that was never fore-sought for the instrument, and this album was the first physical representation of his genius. Sourced from the only copy of the original master tapes in existence.”

If you know Wadud, who died in 2022, it’s likely through his work with the late St. Louis saxophone player Julius Hemphill, an affiliate of the Black Artists Group who invited the cellist to be part of his trio in the early 1970s. They’d met while Wadud was attending music school at Oberlin College in Ohio.

Recalled Wadud in a fascinating interview with Tomeka Reid and Joel Wanak for Point of Departure:

Abdul: While in college I had to perfect the economy of doing both, playing jazz and avant-garde and classical music. The classics also aided me in furthering my avant-garde ventures tremendously. That’s where I met Julius Hemphill, when I was a junior at Oberlin. He came down for a concert and we hooked up. From then on we started working together.

Wanak: He came down to just hear a concert?

Abdul: No, to perform. We had a black history professor, Oliver Jackson. He made the hook up between me and Julius. Oliver was from St. Louis as well and he was familiar with the Black Artists Group – BAG. Me and Julius hooked up and we started playing together. I also had a professor at Oberlin. Ollie Wilson played bass. He was into electronic music and avant-garde.

In addition to Hemphill, Wadud recorded or gigged with artists including Muhal Richard Abrams, Cecil Taylor, and Sam Rivers.

Considering the bona fides, that Wadud didn’t release By Myself through a contemporary avant garde jazz label might be surprising; its vision seems tailor-made for ECM. That, however, was by design, Wadud told Reid and Wanak when they asked him about recording and releasing By Myself.

“At that time people were doing that. We were doing that. We branched off and people were expressing themselves that way [with solo recordings],” Wadud said. “So, I wanted to do one for the cello as well. I originally planned to do three and I didn’t get around to it.”

Asked about putting the record out himself, Wadud replied that it “was definitely a self-produced situation. I had offers to do it with some labels, but I wanted to do it myself and have control of what I was doing.”

He released it on his Bisharra Records label. The lack of promotion and distribution doomed the record, at least commercially. It didn’t stay in print long, and when Wadud unexpectedly retired in the early 1990s, his work seemed to retire with him.

You know what happened next: Private press brilliance + rarity + YouTube upload = Increased demand, increased value, and reissue.

But the secret to the above equation is tucked within the grooves itself. Wadud’s record is unlike anything before or after it. How come? The cellist himself can answer:

“I approached the cello not in the lyrical sense that it was known for. I had a percussive approach at times, chordal approach, as well as linear approach and tried to incorporate all of that depending on the situation and the demands of the music at that time.”