The curator and co-founder of Bonnaroo discusses collaboration, programming instincts and the culture of listening that shapes Big Ears. Ashley Capps has spent most of his career building […]

Alvin Lucier’s Brainwave Music, with John Cage, Reborn From a Lost 1967 Tape

EM Records has rescued a lost 1967 performance of Lucier’s Music for Solo Performer, featuring Cage, David Tudor and Toshi Ichiyanagi. Available for pre-order from In Sheep’s Clothing.

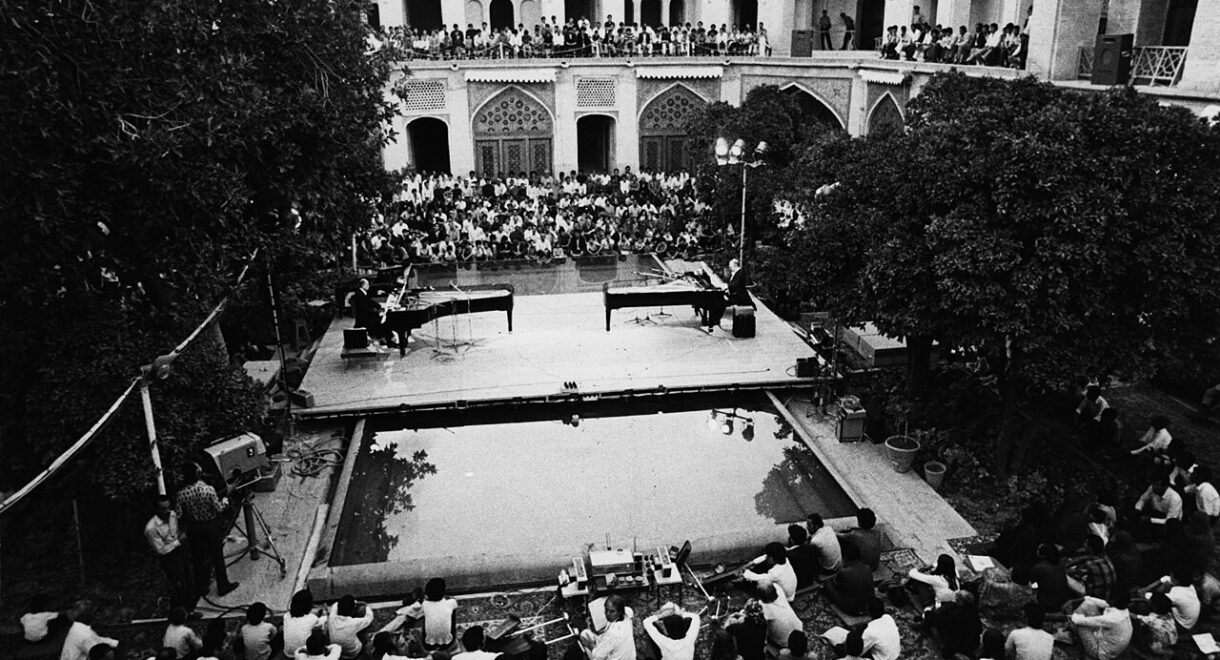

Before the concert at Hope College in Michigan in May 1967, the brilliant composer, sound theorist and mycologist John Cage wandered off into the woods to hunt for mushrooms.

Lowell Cross, who helped realize the performance, remembers Cage discovering a campus kitchen, disappearing into the trees, returning with bread, butter and red wine and sautéing whatever he’d managed to forage. Everyone ate together before walking into the chapel to perform. Cage, Cross writes, was as pleased with his role as cook as he was with the concert itself.

That detail tells you almost everything about what kind of event this was. Featuring Cage, Toshi Ichiyanagi and David Tudor performing compositions by Ichiyanagi and Alvin Lucier, the night was less an academic presentation of avant-garde works than a temporary community built for a night, where electronics, bodies, food, chance, and attention all belonged to the same system. EM Records has now secured a tape of that set and is reissuing it on vinyl and CD this February. It’s available for preorder from In Sheep’s Clothing now.

Cross, who died in 2021, was not just an observer. He was one of the founding members of the Sonic Arts Union alongside Lucier, Gordon Mumma and Robert Ashley, a group that more or less invented what live electronic music in America would become. Cross was the one who could make ideas work in the room, translating theory into circuitry, turning EEG signals, oscillators and percussion into something that could actually be performed.

The music they made that evening sits at a rare intersection. Lucier was just beginning the series of works that would explore sound as a physical phenomenon. Tudor had already begun shifting from being a legendary pianist into something stranger, a builder of electronic environments that performers moved inside.

Fluxus member Ichiyanagi had brought Cage’s indeterminate ideas back and forth between New York and Japan and was folding them into his own hybrid of live electronics and acoustic gesture. Cage himself, by then deep into his systems-based phase, was less a composer delivering pieces than a facilitator of situations.

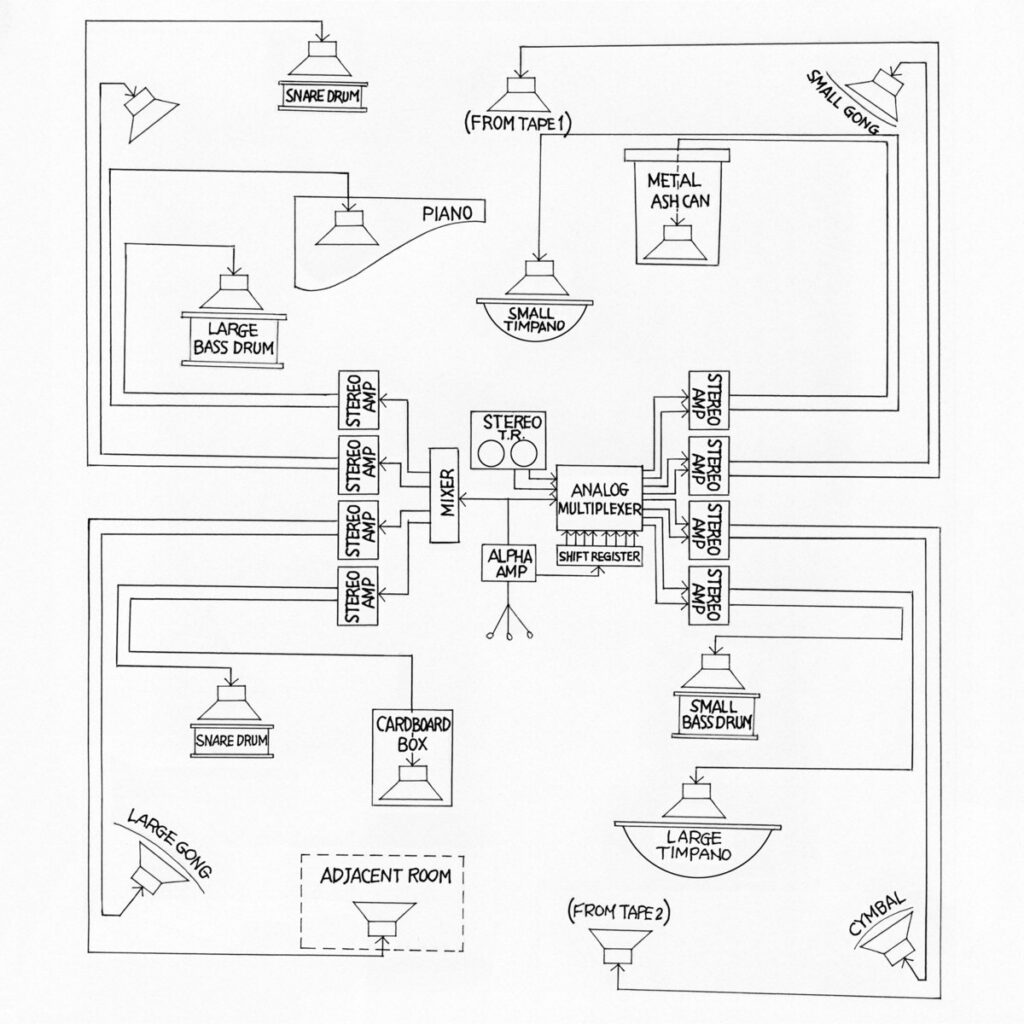

Lucier’s Music for Solo Performer, heard here in an early realization, is often described as the first piece to use brainwaves as a musical source. Electrodes detect alpha waves from the performer’s scalp and translate them into triggers for percussion instruments. On this 1967 tape, though, it does not sound like a clean scientific demonstration. With Tudor and Ichiyanagi shaping the amplification, it comes off as raw, metallic and almost industrial, closer to a room full of unstable machinery than to the meditative version Lucier and Pauline Oliveros would later record in 1982.

These tapes sat in a Japanese archive for decades before being rediscovered, and the liner notes by Ibe Osamu, Minoru Sato and Ichiyanagi himself trace that unlikely survival. But the real story is what they capture: a moment when experimental music was still something you cooked, wired and inhabited together. Which is to say, the mushrooms, the wine and the circuitry all belonged to the same piece.