Let’s talk about Roberto Musci, the Milanese experimental composer whose work both alone and with kindred spirit Giovanni Venosta starting in the 1980s has been gaining attention and […]

Carla Bley and the New Music Distribution Service: Seeding jazz and experimental culture with brilliance

The late composer co-founded “a kind of musical version of the hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy, with every entry registering like a report from some farflung orbital station.“

Records are heavy and they take up a lot of space, which is fine if you’re working on a collection, have decent shelving and are adding new albums a few at a time. But if you’re an artist or record label, boxes of records are way, way too heavy and take up way, way too much space. Before the drop-shipping era, artists and independent labels without a major label backing them had to have a distributor or store them on their own.

Problem was, if you were making esoteric, challenging music that way that, say, pianist and composer Carla Bley was when she was starting out in the 1960s and early ’70s, finding a distributor was next to impossible.

Bley, who died on Tuesday at 87 after a brilliant life in music both as an artist and as label owner (WATT), might be best known for her work, but as a relentless supporter of new music she’ll also be remembered for the New Music Distribution Service, which she cofounded, like WATT, with the musician Michael Mantler. As Forced Exposure distribution noted on its Instagram:

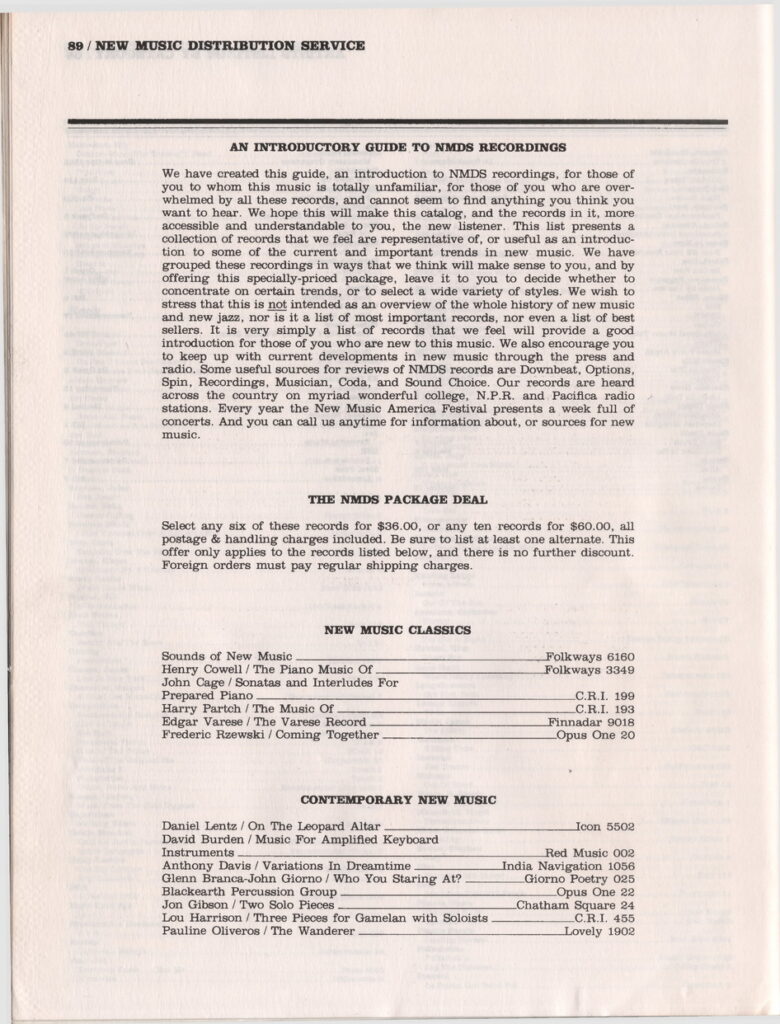

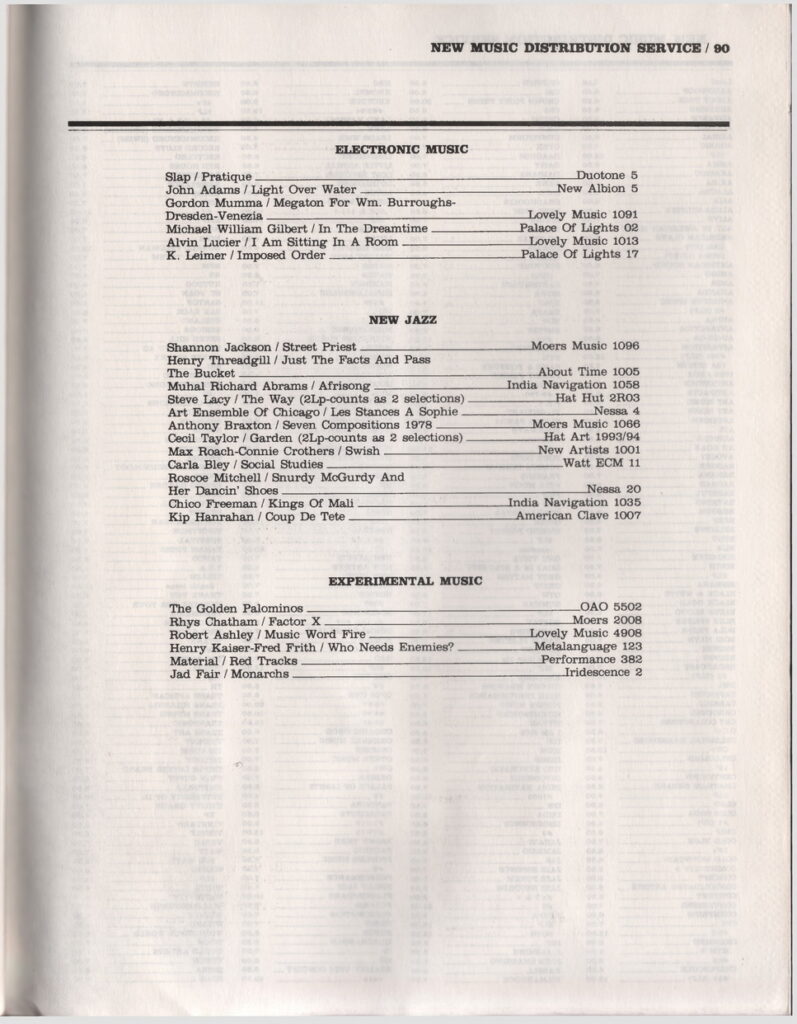

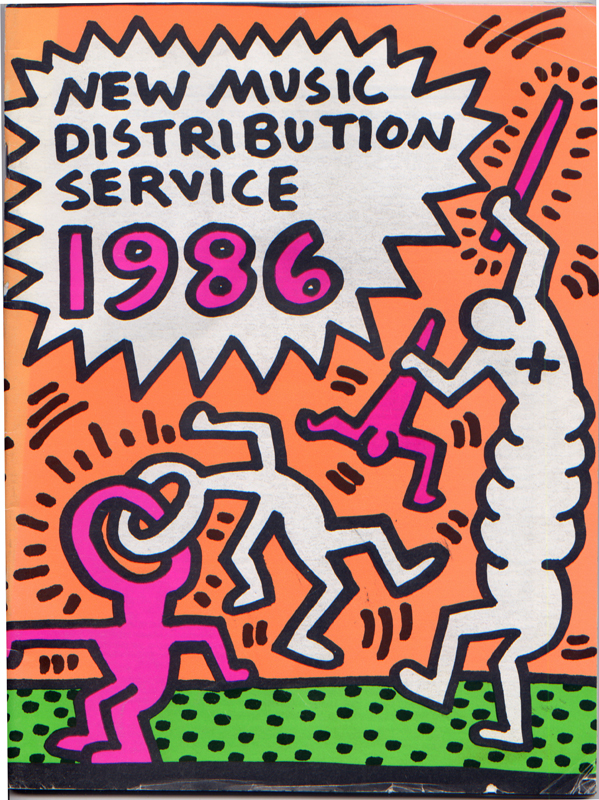

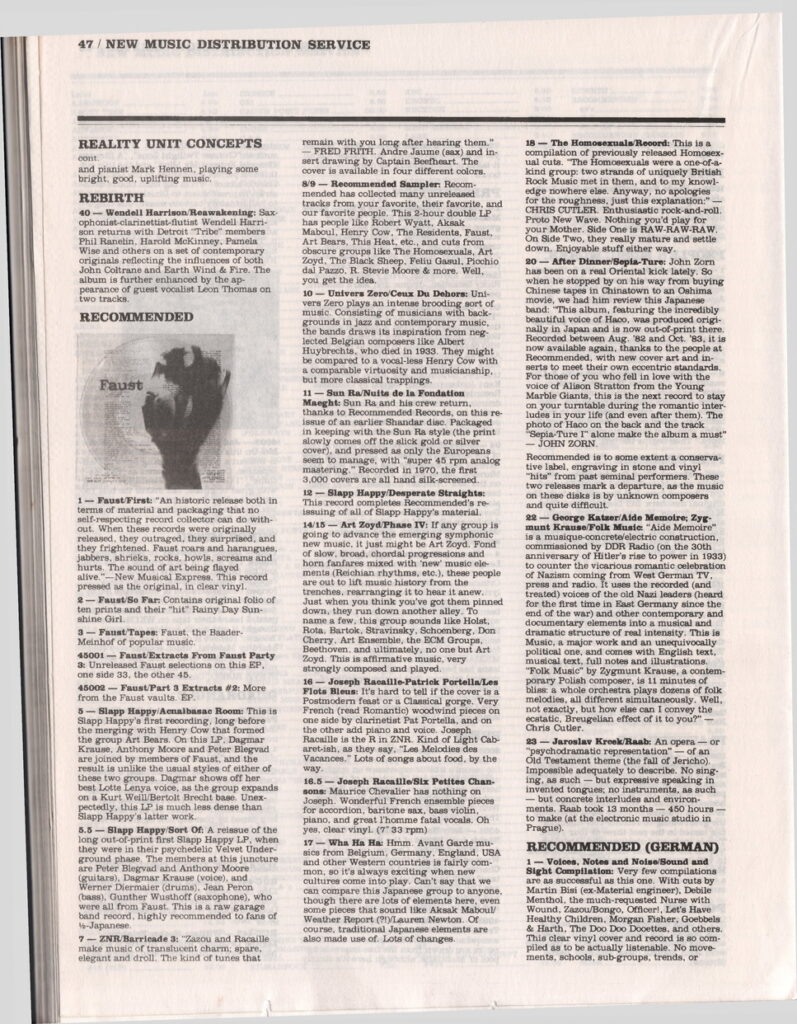

Besides her 60+ year career as composer/ performer, she notably co-founded the NYC distributor New Music Distribution Service (NMDS), which ran from Approx 1972 through 1990. They had beautifully designed catalogs, really nice order forms, credit card acceptance way back, and easy to decipher price lists — back in the day when most labels sold all LPs at the same price. Legendary.

In a great interview for the New Music USA website, writer Frank J. Oteri asked Bley about the NMDS, which had its headquarters on Broadway about eight blocks from In Sheep’s Clothing NYC.

Frank J. Oteri: Let’s talk about New Music Distribution Services. How did that get started?

Carla Bley: That got started because Mike and I had made our own recordings, two for JCOA by that time. Mike’s album was called the Jazz Composers Orchestra and mine was Escalator Over The Hill. What do you do with them once you have them? Do you pile them up in your living room or something? You’ve got to get them distributed. We quickly found out that you have to get these things distributed. How are we going to do that? No distributor is going to want them because we don’t have any reputation. So we got together with 10 different labels that we knew about. I believe they were all European at the time. In England it was Incus. In Germany it was FMP and ECM, Futura in France. It was all these people like us: weird people who got their own money together and made their own strange recordings.

Oteri: And it wasn’t just jazz. It was also contemporary music. Lovely Music was a part of that early on.

Bley: That was later. This all started with jazz because that was the only people we knew at that point. There were maybe 10 of us, and we distributed each other’s records. We did this for a couple of years for free. If we have a new record we would send it to all these countries. If they had a new record out they would send it to us. We would each try to distribute them as best as possible: to stores or to friends, take out ads, whatever.

The catalogs were more than just listings of stuff for sale, though. They were founts of information in a pre-internet era when such knowledge was hard to come by.

The brilliant critic Greg Tate explains it better, of course, in his introduction to the 1986 catalog.

Some folk probably just think of the New Music Distribution Service catalogue as this encyclopedic warehouse stocked with mostly independently recorded jazz and contemporary Euro-American classical music. The more savvy perhaps see it as a networking resource for pro-ducers, performers and composers of experimental music.

But for reasons that will probably perplex no one I tend to think of each year’s New Music Distribution Service catalogue as a kind of musical version of the hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy, with every entry registering like a report from some farflung orbital station. Flipping through its pages can provoke goose pimples of the order of those brought to flesh when Carl Sagan’drones on about how many billions upon billions of star systems there are out there and that no, we are not alone.

If you’re a music lover of eclectic and exotic listening habits you’ll find consolation in this catalogue and a kind of communion with others the Master Programmer also gave extraterrestrial ear lobes to.

Added Bley of her blunt approach in an oral history project for the Smithsonian Institution:

I just put out the newspaper and did the… I went to dinner with people and I said everybody should make his or her own album. Don’t give the music to the companies, and I would talk to the companies and say, “Everything you get you stole from us, so why don’t you give the money now and I’ll do more work with people putting out their own albums, and then you can steal from more records.” And that didn’t go over very big. Every business deal I tried failed, except that I put out my own records and had complete control over all those twenty five years. More.

Later in that Oteri interview, he asks Bley about her early exposure to jazz in New York in the 1960s, which leads to a fascinating revelation.

Oteri: I want to know more about you being a teenager and winding up working at Birdland. Those were very heady times for jazz in New York.

Bley: Oh, I was there! I saw it all, except I got there a little after Charlie Parker. Otherwise, I saw it all, I think. God, I can’t believe those days! I just wanted to hear the music and I didn’t have any money. So I thought I’ll just get a job there and that was so smart. That was my education. I worked at Birdland, Basin Street, the Jazz Gallery, and the Five Spot a little bit, as anything. As a cigarette girl, as a seller of stuffed animals, as a photographer with a camera around my neck… I would go up to a table and say, “Would you like a picture of you and your girlfriend.” And the guy would say, “No! God!” I think I maybe took only two or three pictures the whole time I worked as a photo girl. I would just stand next to the bandstand and absorb all the music. That’s where I learned everything.

Bley and Mantler put that learning to work — while continuing to absorb knowledge and share it with others. Original catalogs are hard to come by, and we’ve only been able to find PDFs of one. But they occasionally come up on eBay. Originals of the Haring edition go for more than $500.

Below, note an amazing deal that NMDS offered. Pick any 10 records for $60!