The late Mexico City composer’s recordings move like Autechre and Aphex Twin tracks. Before MIDI or the 808, before Ableton, before the first home computers, an Arkansas-born, Mexico […]

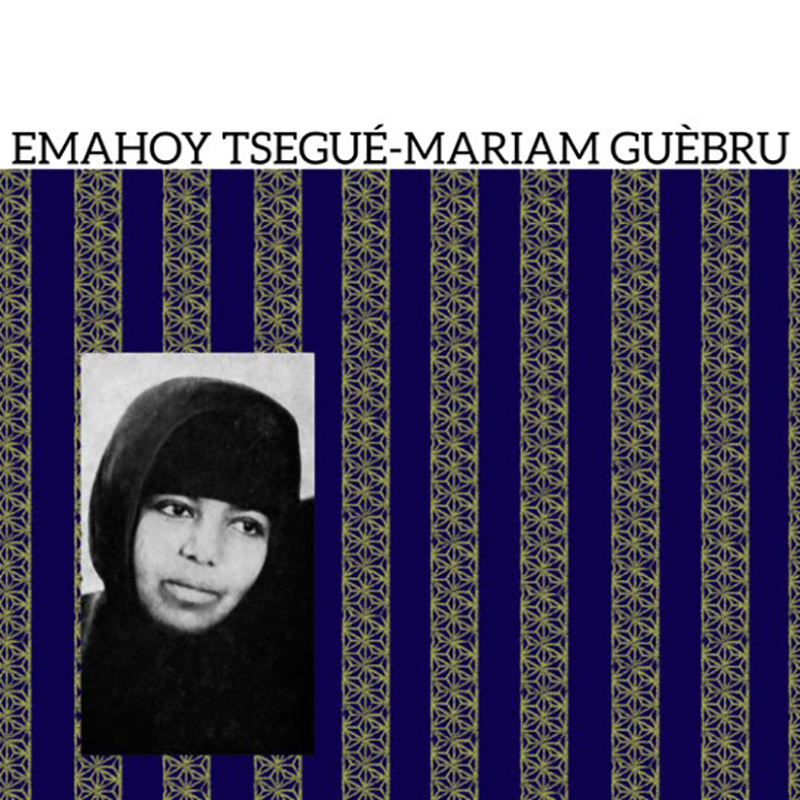

The Honky Tonk Nun: Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou

Andy Beta reflects on the close and unknowable music of Ethiopian jazz pianist Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou.

Last week, I visited my local coffee shop. Most days, the soundtrack trades in a warm and buzzy mix of golden era Blue Note post-bop, but some mornings it can turn contemplative. Think Bill Evans Trio Sunday At The Village Vanguard, Evans’ duo with Jim Hall Undercurrent or Alice Coltrane’s Turiya and Ramakrishna. On this particular morning, a deeply familiar piano rang out in the space. The owner and I exchanged a knowing nod: It was the sound of Ethiopian nun and pianist, Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou.

You no doubt have encountered in some public space one of the 16 compositions she recorded (out of the hundreds she’s written), as Guèbrou’s music seems to be part of the ether. It’s employed as background music for a novelist or artist deep in concentration or as a mood-setter at a low-key get-together. It comes up in the YouTube algorithm. Norah Jones overheard it at someone’s house, instantly resonating with “one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard: part Duke Ellington, part modal scales, part blues, part church music.” Director Kelly Reichardt lamented to Pitchfork: “It was a secret and now it’s in every sandwich shop you walk into … like, ‘Oh my god, the nun record’s here, too.’”

Even if you heard Guèbrou’s piano in an ad for Amazon’s Echo Smart speaker, on a BBC programme or as soundtrack for director Garrett Bradley’s recent documentary Time, or at your local coffee or sandwich shop, Reichardt is wrong about the tense: Guèbrou remains a secret. Even thousands of listens to songs like “A Mother’s Love” or “Homesickness,” it feels at once close and unknowable. The indie director goes on to note one of the most fascinating qualities of Guèbrou’s piano music: that each listener –initiate or familiar– establishes an intimate connection with that record. Her music transmits between friends. Even hearing her at my local coffee shop stems from such exchange, in that I first suggested that the owner check out her music. Emahoy’s music feels so deeply connected to me that my own memory has all but eradicated just how I first encountered “the nun.” I knew a few entries in the Ethiopiques series, which was launched by Buda Musique in 1997, but who was it that first introduced me to — as one writer described it -– “the sonic equivalent to infinity … as if Guèbrou’s instrument holds more keys than it should”?

Why did a teenager, freed from the shackles of war and poised to perform music for a living, abandon it all for a nunnery? Guèbrou would only say: “It was His willing.”

Now 96, Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou’s life similarly holds more than the seven decades living in a monastery would suggest. She was born Yewubdar Guèbrou in 1923 to a prominent Ethiopian family. She grew up in great privilege, sent with her sister to study at a Swiss boarding school. Piano and violin lessons there revealed her to be a musical prodigy and she gave her first piano recital at the age of 10. When she returned to Addis Ababa as a young teen, she attended fancy parties, raced a horse and trap around the city, and even sang for the recently-crowned Emperor Haile Selassie.

A Guardian profile from 2017 posited Guèbrou as a feminist in the African country: the first woman to work for the Ethiopian civil service, to sing in the Ethiopian Orthodox church. “Even as a teenager I was always asking, ‘What is the difference between boys and girls?’” she told the reporter. “We are equal!”

But when Benito Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935, his forces killed three members of Guèbrou’s family and forced her and the rest of her family into prisoners of war on the Italian island of Asinara. After the war, Guèbrou says she was offered a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music, but didn’t go. Instead, the 19 year-old fled the city of Addis Ababa, traveling nearly 500 kilometers north to enter the mountainous Guishen Maryam monastery.

Why did a teenager, freed from the shackles of war and poised to perform music for a living, abandon it all for a nunnery? Guèbrou would only say: “It was His willing.” By 21, she was an ordained nun, casting off the comfort, lifestyle, and privilege her upbringing had afforded her to be barefoot in the mountains of Ethiopia. She was given the title Emahoy and her name was changed to Tsegué Maryam, or Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou.

Despite the demands of her devout new lifestyle, Guèbrou dedicated even more time to her music, practicing up to 9 hours a day. By the early 60’s, she had moved from the Guishen Maryam monastery to Gondar in the west. There she studied the music of St. Yared, the 6th century saint of the Ethiopian-Eritrean Orthodox Church and composer of the liturgical music of the church whose Mahlet remains studied and is still performed today. Struck by the group of young, homeless students studying the liturgy at the church, Guèbrou remembers on her website: “Although I did not have money to give them, I was determined to use my music to help these and other young people to get an education.”

With assistance from her old friend Emperor Selaissie, she recorded five of her own compositions and released them in 1967 on a German label. Her sister assisted on another recording in the early ‘70s, this one directing all proceeds to helping an orphanage for children of soldiers. The Emahoy Music Foundation to this day remains dedicated to providing music scholarships to children in Ethiopia and Israel. Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou still lives in a cramped room at the Ethiopian Orthodox church in Jerusalem, playing for hours a day on a piano tucked into her room. There are portraits of Emperor Haile Selassie and her own paintings of religious icons on the walls. She composes music and there may be a future date when these other works can be heard outside of her monastery.

It’s these handful of recordings that comprise Guèbrou’s legend as “The Honky Tonk Nun.” But who imagines the sound of “honky tonk” when hearing her play? While Guèbrou’s recordings comprise the 21st volume of the Ethiopiques series, positing her alongside titans of Ethio-jazz like Mulatu Astatke, Alèmayèhu Eshèté, and Gétatchèw Mèkurya, she insists she’s not a jazz artist. Depending on your own listening history, you might hear something familiar and resonant in her piano works. Maybe it evokes those Ethiopian artists or the deep foundation of St. Yared and Ethiopian liturgical music. Western classical fans might hear Chopin, Schubert or Debussy. Jazz listeners may glean traces of Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, or the likes of Oscar Peterson and Fats Waller. One can feel the blues, ragtime, gospel in her playing, or the township piano of Abdullah Ibrahim in her voicings, in her flowing, highly lyrical runs. And yet it doesn’t seem to come from late 19th century/ early 20th century African-American music so much as from what might predate that, the Pangaea of those subsequent forms. For me, her tone feels like a preternaturally calm yet mysterious body of water, unfathomably deep, “The Song of the Sea” itself.

While instrumental, Guèbrou’s music gives voice to something much deeper and primal. It doesn’t seem to be a coincidence that her titles speak to unplumbed emotional states, feelings that have shadowed us for centuries. “Mother’s Love,” “Homesickness,” “The Homeless Wanderer,” “The Last Tears Of A Deceased,” such resonant, guttural vibrations never leave us, no matter what else might change or evolve. Richard Brody’s words about Time, the recent film that draws heavily on Guèbrou’s music for its soundtrack, touches upon a quality of these pieces, “a sanctification, the placing of a divine weight, a community responsibility, and a cosmic value on the expressions and gestures and activities of daily life.”

Hearing Emahoy’s music that day at the coffee shop was routine, but it also took on a bittersweet cast. My local coffee shop was shuttering, the once vibrant hub of the neighborhood yet another one of the economic casualties of the pandemic, a signifier of greater stresses and hardships that still lie ahead for people, for local businesses, for the greater community. The owner’s words stuck with me while discussing her: “This isn’t music. This is medicine.”

Listen to a compilation of Emahoy’s piano works below: