“Dubwise but not exactly dub, rich in ambience but not exactly ambient music.” With three of the classic Sade albums (Promise, Diamond Life, Stronger Than Pride) recently repressed […]

Enossified: Brian Eno Collaborations 1973-1980

Collaborating with Brian Eno is like having your very own alchemist in the studio. Almost everything he touches turns to gold.

In the interest of keeping the In Sheep’s Clothing HiFi virtual record collection diverse and not overdoing it with Eno, which is tempting, we’ve opted to create a space dedicated exclusively to our beloved music polymath: a compilation of our favorite Eno albums outside of his solo career, highlighting his gifts as a collaborator, co-writer, producer and musician.

The art school graduate and self-described “non-musician” is easily one of the most creative, prolific, influential musical innovators in our lifetime. His synth contributions to iconic glam rock group Roxy Music; his coining of the term ‘ambient music’ and molding the genre; his co-creation of the revelatory card deck Oblique Strategies; his production of the definitive 1978 no wave compilation No New York; and his extraordinary sound installations and infinitely looping computer-generated compositions.

In the words of journalist Lester Bangs circa 1979, Eno is “unique enough to be truly confounding.” Everything about him is a contradiction. He’s a serious composer who doesn’t know how to read music. A rock star who doesn’t have a band and never tours, also enjoying the feat of being allowed by his various record companies (mostly Island) to put out an average of two albums a year since 1973 when none of them has sold more than 50,000 copies. (In the midst of this prolific output, he was quoted in pop papers everywhere, insisting he was not a musician at all.)

The list of artists Eno has joined forces with is too long to detail – everyone from Grace Jones to Seun Kuti to Ultravox to James Blake to Laurie Anderson (and even U2 and Coldplay?!). Whatever studio Eno goes to, he brings his box of tricks. Sometimes it’s quite literally in the form of a box, like his Oblique Strategies box of cards encouraging lateral thinking, or his trusty “synth in a suitcase” (the EMS Synthi AKS). Other times the tricks are in his beautiful brain brimming with wizardly techniques and theories.

Working with Eno means reaping the benefits of his mind-opening creative exercises, his zen approach to the addition and subtraction of musical elements, his unconventional, boundless approach to the idea of the music studio itself as as instrument or compositional tool, his fascinating love/hate relationship with lyrics and vocals, and his love for preserving mistakes and accidents. Even his playful attitude towards music has the power to free those he works with from the seriousness of music or of the self — the ego bows down, fear subsides, the inner child emerges, and self-confidence materializes. A priceless example of Eno’s imagination at play: while working with Coldplay, Eno suggested they try playing while hypnotized, and invited his hypnotist friend to the session: per bassist Guy Berryman, “one of his friends came down and we tried it out. Nothing came of it but at least we tried it.”

Here is a list of our favorite albums demonstrating the magic alchemy of Eno. It is an approximately chronological list based on year recorded (in some instances precise recording dates are unknown).

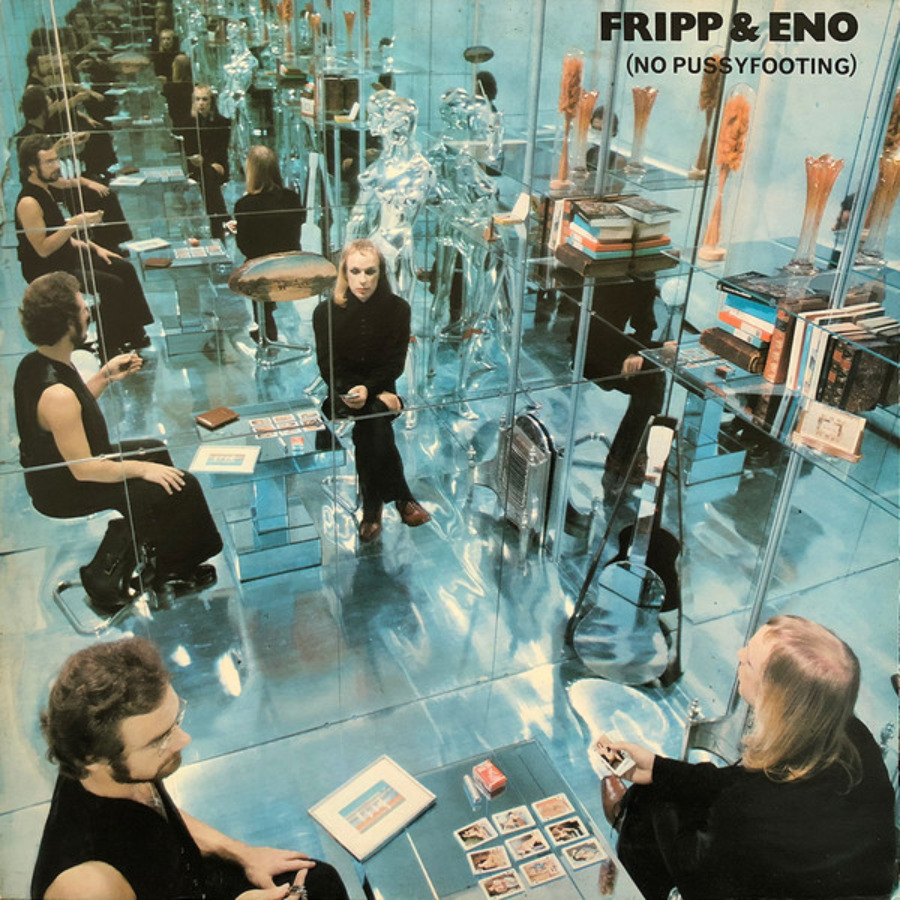

- ARTIST: Fripp & Eno

- ALBUM: (No Pussyfooting)

- RECORDED: September 8, 1972 + August 4–5, 1973

- RELEASED: 1973

- LABEL: Island Records

- STYLE: Experimental, Electronic, Proto-Ambient, Drone

(No Pussyfooting) was a collaboration between Brian Eno and Robert Fripp (famously of King Crimson), with shared writing, performing, and producing roles. Eno’s instrument credits include synthesizer (specifically the VCS 3 synthesizer) and keyboards. He is also credited with ‘treatments,’ referring to the unique process of manipulating sound that became Eno’s trademark, so much so that Genesis actually gave a name to his synthesized effects — ‘Enossification’ — in the credits of their 1974 album The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway. (No Pussyfooting) was a fruitful tag-team between like-minded forward-thinking playmates. Fripp was the creative conduit Eno needed during the final, stifling stretch of time in Roxy Music.

With Eno’s London home studio serving as the lab, the mad scientists devised a technique later dubbed ‘Frippertronics,’ incorporating Fripp’s electric guitar performance into an elaboration of the reel-to-reel tape recorder looping system pioneered by composers Terry Riley and Pauline Oliveros in the 60’s. Both Eno and Fripp would continue to hone tape looping in their subsequent work both separate and together.

(No Pussyfooting) was the first of Eno and Fripp’s many synergetic studio moments: e.g. Fripp’s transcendental guitar on some of Eno’s best solo work vocal tracks: “Baby’s On Fire” (from 1974’s Here Come the Warm Jets) and “I’ll Come Running”/“Golden Hours”/”St. Elmo’s Fire” (from 1975’s Another Green World), as well as Fripp’s transcendent playing on David Bowie’s 1977 album Heroes per Eno’s suggestion. Add in three additional studio albums as the side project Fripp & Eno, and it becomes clear that (No Pussyfooting) was an early glimpse of the magic Eno would go on to create in the sonic spheres…

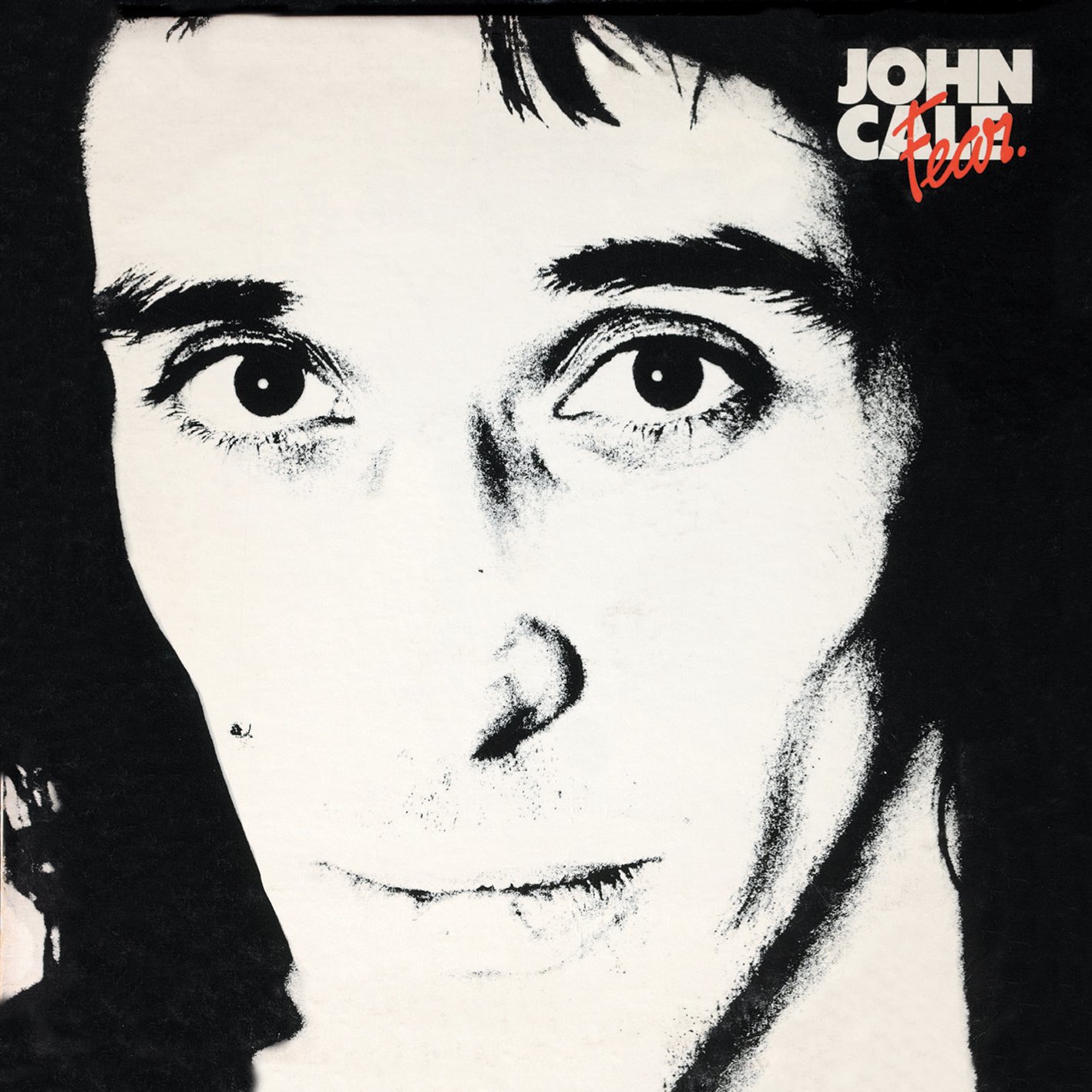

- ARTIST: John Cale

- ALBUM: Fear

- RECORDED: 1974

- RELEASED: 1974

- LABEL: Island Records

- STYLE: Art Rock, Experimental, Glam

The fourth studio album by Welsh musician and Velvet Underground bassist/viola player John Cale features the second best album credit ever ascribed to Eno (the first being ‘Enossification’): “Eno: Eno,” which implies that Eno does not play instruments– he is an instrument. A flesh-and-bones vessel into which music flows and undergoes a process of synthesis before its exodus.

The liner notes elaborate that Eno contributes synthesizer and effects, and also executive-produced the album alongside former Roxy Music bandmate, guitarist Phil Manzanera, under the lead production of Cale. The track “Gun” bears Eno’s mark, expanding upon his previous guitar manipulation experiments with Fripp, this time using electronics to process Manzanera’s guitar solo in real-time.

It’s worth noting that slightly contentious Cale-Eno interactions in the studio would have made for sitcom gold, with rock and roller Cale’s whirlwind behavior in stark contrast to the tea-sipping, philosophizing zen master Eno. The latter described Cale’s frustrating talent as “bursts of genius interspersed with oceans of inattention.” And yet, despite their differences, they would repeatedly work together: they joined forces with Nico, Kevin Ayers, and others for the live album June 1, 1974; Cale played beautiful viola parts on “Sky Saw” and “Golden Hours” from Eno’s Another Green World, and again on his 1978 album Music for Films. They even did a full-blown studio album collaboration, the sorely underrated 1990 album Wrong Way Up.

Brian Eno recounts the Fear experience :

“I play much less than Phil because that wasn’t the role I was fulfilling anyway. And generally, I was a kind of consultant or advisor, anyway. John was using me to bounce ideas off of, and get reactions from. It was a very intense month, it took a month to do and it was a month of solid work. I considered myself totally committed to that album at that time; John would ring me up at half past five in the morning and say ‘I’ve just had this idea for such and such, what do you think?’, and we would talk for one half hour. And I considered it part of my role to do that because that was really my only role at the time. I wasn’t sort of putting hot licks on the album. And it was interesting – being this sort of consultant, ideas consultancy. It was very pleasant and the album is tremendous; I think it’s the best John Cale album really – it has a whole other direction on it that he hasn’t touched before.”

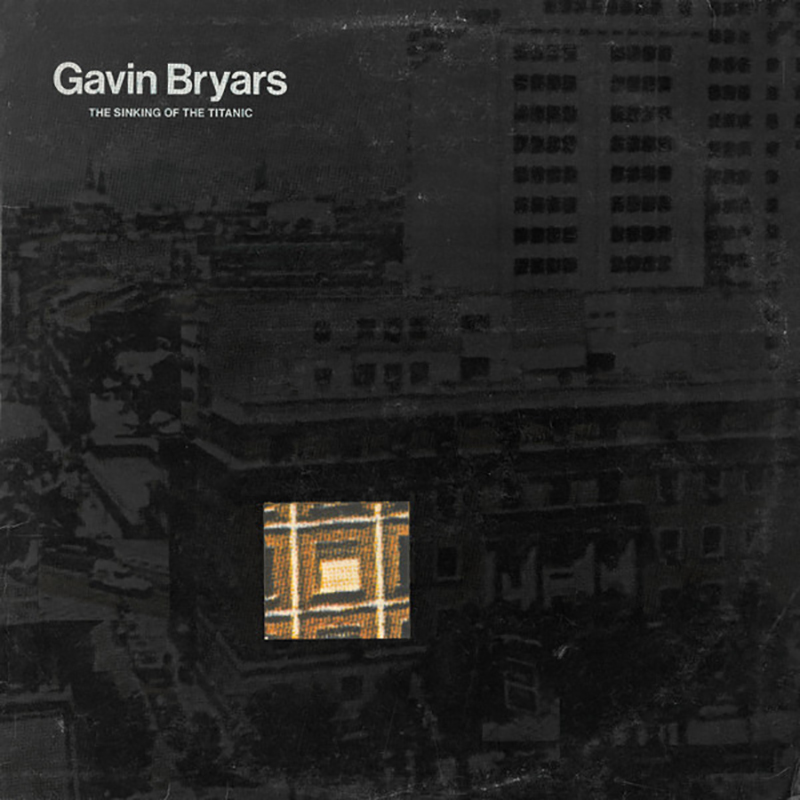

- ARTIST: Gavin Bryars

- ALBUM: The Sinking of the Titanic

- RECORDED: 1975

- RELEASED: 1975

- LABEL: Obscure Records

- STYLE: Experimental, Electronic, Modern Classical, Minimal

Eno produced The Sinking of the Titanic by British minimalist composer Gavin Bryars as the first release on Eno’s own label, Obscure Records (an Island Records imprint, active 1975 to 1978). The release consisted of two orchestral, slow-building composition: “The Sinking of the Titanic” on one side and “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet” on the other.

Bryars composed “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet” in 1971 and “The Sinking of the Titanic” between 1969 and 1972. He had been workshopping “… Titanic” in live settings as an abstract art piece. Eno’s recording was the first time Bryars solidified the ever-evolving piece into a fixed form on tape. (He would later re-record the work for a 1990 release, and again for a 2007 release.)

Bryars and Eno first met in 1969 when Eno saw one of Bryars’ experimental performances at an art college. They were a sympatico pair in the studio: friends, mutual admirers of each other’s work, and innovators cut from the same cloth, both tinkering with the confines of music. Bryars was the impetus for Obscure Records, and the first under-the-radar composer whose music Eno endeavored to release. In Eno’s own words, “It was really because I felt so strongly about The Sinking of the Titanic and Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet that I persisted with my idea to have a record label on which to get them released”.

Leading record labels’ business models, of course, usually target popularity, not obscurity. Yet by some miracle, Island Records/Chris Blackwell had enough faith in post-Roxy-Music Eno to green light the manufacturing and distribution of Obscure Records, a label whose ill-fated mission statement is embedded right there in the name.

As Bryars explained, “it was his increasingly prominent position within the recording industry that enabled us to record in 1975 and to start the series of albums called Obscure Records.” Of their lack of intention to actually sell product, Bryars added, “‘Obscure’ was the name that Brian and I came up with… At that time I was interested in the whole idea of research, and in the pleasure one would take in finding something that had been a real struggle to locate… and the idea emerged that we would, in fact, make it quite hard to find these records. Initially they were even only available on mail order, which meant that there was no real critical response to the albums. As a marketing strategy this is clearly flawed…”

To no surprise, the highly avant-garde work was not everyone’s cup of tea, including the actual musicians on the recording. Bryars confessed, “for the recording of ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet’… I had to hire many orchestral musicians, including members of the horn section of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. But the list of personnel on the recording has none of their names… these professional players really hated the music and they left quickly at the end of the sessions, leaving their invoices and insisting that their names should not appear in the album credits, saying that this could ‘damage their reputations’… On the other hand my friend the late Derek Bailey told me once that he had had more drinks bought for him because he was the guitarist on the original recording of ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet’ than for any other reason!” Although the initial reception was unsensational, the work eventually gained cult status, forever cemented as a British experimental music classic.

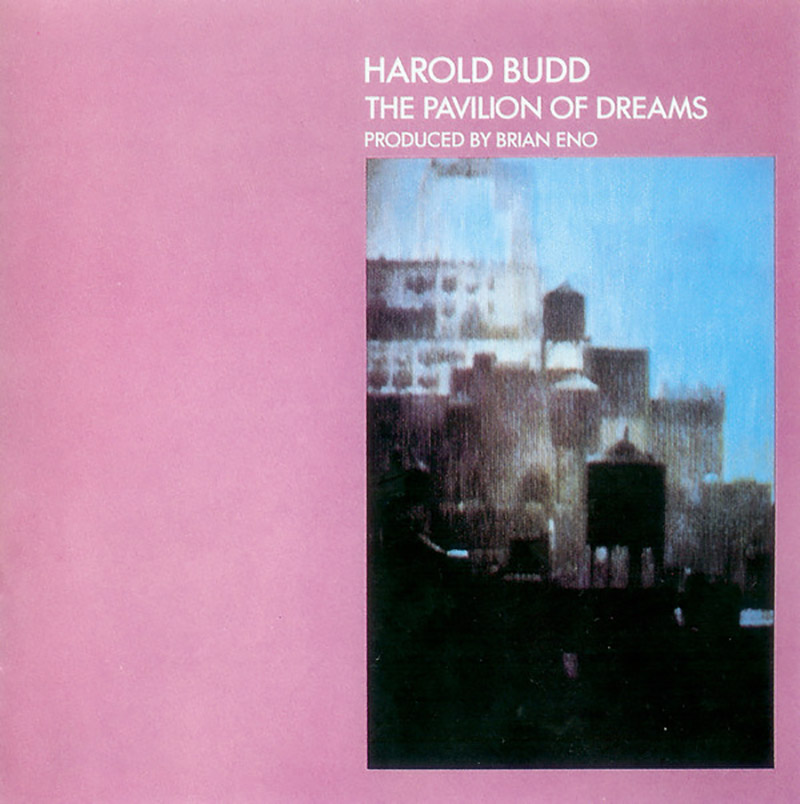

- ARTIST: Harold Budd

- ALBUM: The Pavilion of Dreams

- RECORDED: 1976

- RELEASED: 1978

- LABEL: Obscure Records

- STYLE: Modern Classical, Minimal, Avant-Garde, Ambient, Electronic

The Pavilion of Dreams is the quintessential sophomore album by avant-garde minimalist composer Harold Budd, and in Budd’s words, the beginning of his life as a serious artist. The album consists of an extended cycle of works conceived in 1972, recorded in 1976 and eventually released in 1978. Produced by Eno and released on his limited imprint Obscure Records, the album features yet another incredible, wizardly Eno album credit: “Voices.”

Eno and Budd met through Bryars (who contributed vocals and glockenspiel on the album), and the pair would continue on to future collaborations such as 1980’s Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror and 1984’s The Pearl, immortalizing their status as “the godfathers of ambient.” Their fruitful first collaboration on The Pavilion of Dreams birthed a beautiful, melodic, cinematic album that feels almost like a noir score. Although Eno had not yet coined the term ‘ambient’ (this album was recorded two years prior to the recording of his first official Ambient Series album, 1978’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports), it’s clear that Eno already had active interest in extracting beauty from electronics, using the studio as an instrument, and making music “as ignorable as it is interesting” to “induce calm and a space to think.” The experience was life-changing for Budd, who claims he owes everything to Eno, and praises him saying, “the primary thing was attitude. Absolute bravery to go in any direction.”

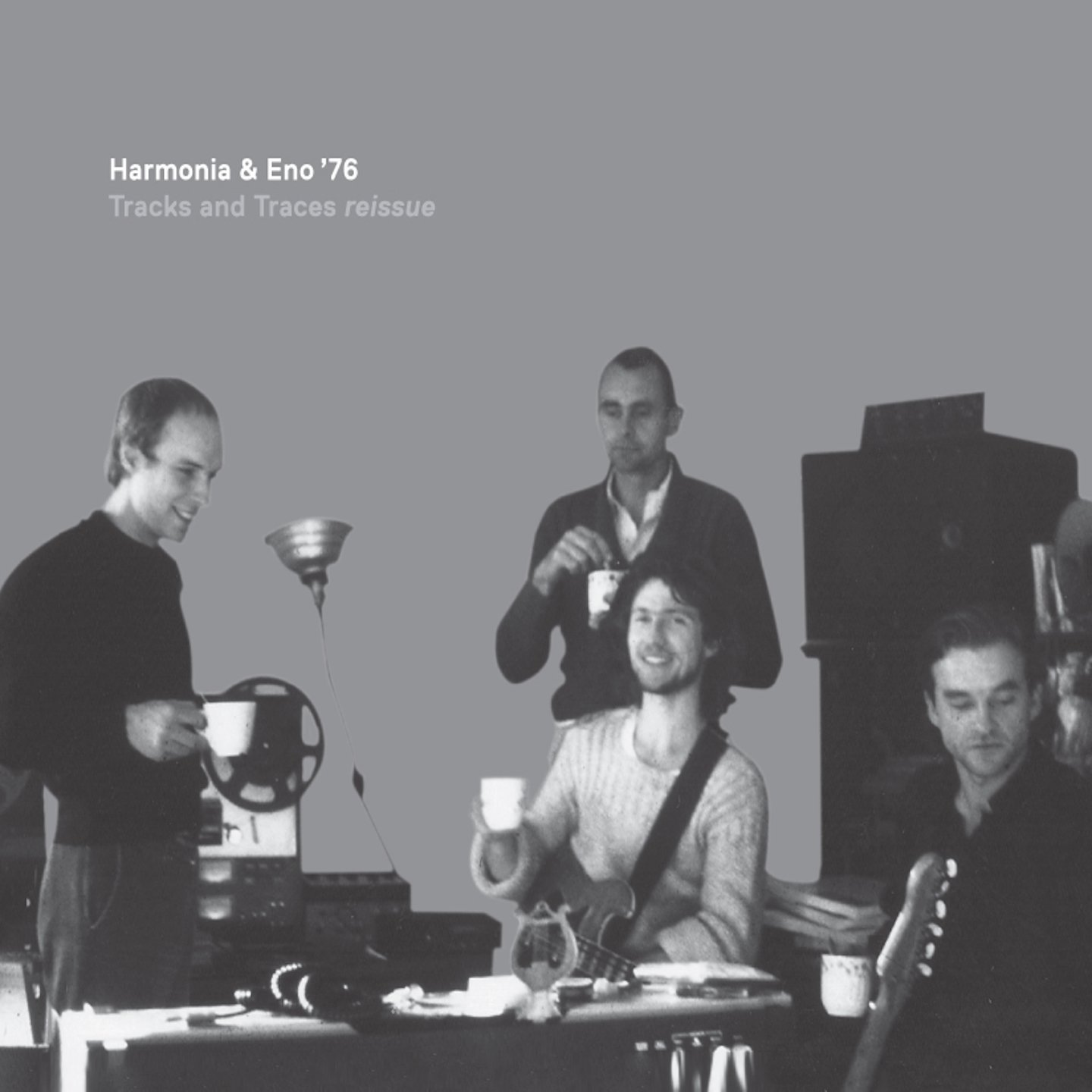

- ARTIST: Originally billed as Harmonia 76 though revised to Harmonia and Eno ‘76 on the re-issue

- ALBUM: Tracks and Traces

- RECORDED: September 1976

- RELEASED: 1997

- LABEL: Rykodisc (US) / S3 (Germany)

- STYLE: Krautrock, Kosmische, Ambient, Electronic

Tracks and Traces is a collaborative album by Eno and the West German kosmische supergroup Harmonia, composed of Cluster’s “synth pastoralists” Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius, and Neu!’s guitarist Michael Rother (previously of Kraftwerk). In September 1976, Eno was about to work with Bowie and Tony Visconti on Low in Berlin. Both Eno and Bowie were enamored with the 70’s German experimental music scene, especially Harmonia. Eno declared Harmonia “the most important band in the world” and Bowie shared the sentiment, viewing them as one of the most important, influential German bands of the era.

Although Harmonia had recently amicably disbanded that summer, Eno’s interest in recording with them reunited them. With his four-track recorder and VCS3 synthesizer in tow, Eno stayed with Harmonia in Forst for eleven days. All four musicians are credited as writers, producers and performers, with Eno credited on synthesizer, e-bass, and voice.

Rother fondly remembered the experience, “Eno didn’t come across like an aloof pop star at all; on the contrary, he was very pleasant and inquisitive. We worked as equal partners and were a collective that simply wanted to make music, with no thoughts of commercial success and without the pressure of having to record an album. To me those are the best working conditions you can have.” In Roedelius’ words, “Eno brought a great intellect, boundless pleasure in making music and a font of experience in the realm of popular music, and that clearly opened a door that was already closed.”

Amazingly, the music did not make it out into the world until more than twenty years after it was recorded. Stories vary: Eno’s tapes were considered lost, or Roedelius and Rother had luckily both made copies of the four-track tapes, or Roedelius retrieved the session tapes from Eno in the 90’s, or some combination thereof. However it happened, the long-lost recordings were released, granting us access to an exquisite time capsule of peak Eno lending his gift for atmospheric frequencies to the sonic identity of Harmonia in a perfect supergroup moment.

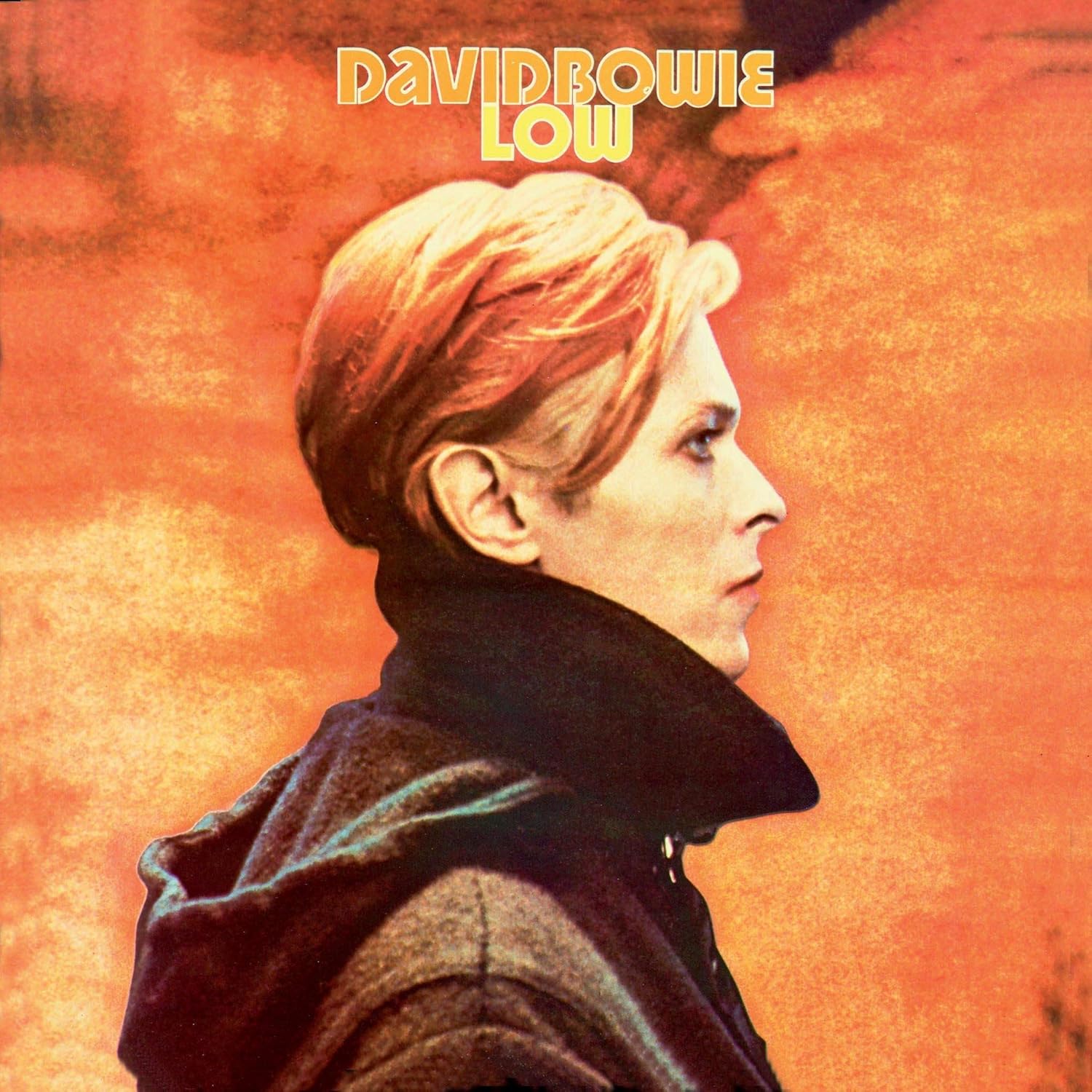

- ARTIST: David Bowie

- ALBUM: Low

- RECORDED: September – November 1976 (except “Subterraneans” – December 1975

- RELEASED: 1977

- LABEL: RCA Records

- STYLE: Art Rock, Experimental, Avant-Pop, Proto-Ambient, Electronic

Shortly after working with Harmonia, and still under the influence of those sessions, Eno arrived in Berlin to collaborate on Low. The album was co-produced by Bowie and his frequent collaborator Visconti, with creative contributions from Eno, who is often mistakenly considered the producer (hilariously depicted by Adam Buxton HERE). Eno wrote and arranged the track “Warszawa,” and additionally contributed Minimoog synthesizer, ARP synthesizer, EMS Synthi AKS, Chamberlin, piano, guitar treatments and backing vocals to the album. This was the first of three albums the trio collaborated on between 1977 to 1979, later dubbed the Berlin Trilogy (with Heroes and Lodger to follow).

Eno’s 1975 precursor-to-ambient albums Another Green World and Discreet Music entered Bowie’s ears and infiltrated his psyche at a very interesting point in the rock star’s career: when the damaging repercussions of his own celebrity (and mainly cocaine) had taken a toll on him, launching him into a period of detox and creative rebirth in the thriving art and music scene of Berlin. Inspired by Eno’s minimalism, Bowie invited Eno to take part, marking a moment in history when both artists were in their creative prime. Eno’s influence is heard most on Side B, where Bowie traverses uncharted territory: instrumental, electronic, ambient, dark, alien, dissonant and atmospheric. Under the influence of Eno’s peculiar, abstract approach to music production, Bowie created what is considered one of his best and most influential works. During a low period in his life, Bowie found a “musical soulmate” in Eno.

Here is a collection of clips of Eno and Bowie talking about each other: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RHHBZMgsXDA

- ARTIST: Cluster & Eno

- ALBUM: Cluster & Eno

- RECORDED: June 1977

- RELEASED: 1977

- LABEL: Sky Records

- STYLE: Electronic, Minimal, Ambient, Experimental

During Eno’s stint in Germany making the Berlin Trilogy with Bowie and Visconti, just a month before working on Heroes, Eno reunited with Cluster duo Roedelius and Moebius, this time without Rother. They collaborated in Konrad “Conny” Plank’s Cologne studio. Plank, an influential Krautrock/Kosmische producer, produced the record along with Cluster. This was the first of two collaborative albums Eno would make with Cluster and Plank, the second being the 1978 release After the Heat, under the revised artist name Eno Moebius Roedelius, with Eno now also credited as Producer.

Eno, Moebius and Roedelius were independently and concurrently laying the foundation for the genre later known as “ambient music” — pastoral synths, sound processing, repetition, looping, minimalism, and atmospheric, textural, otherworldly ambiance. There is admirable beauty in their decision to join forces and share experiments, working harmoniously rather than competitively in the pioneering age of ambient. Their first album together is considered a seminal ambient album, with its 1977 release preceding Ambient 1: Music for Airports by a year (Eno’s first album explicitly created under the term “ambient music”). Cluster & Eno is also considered the first ambient album made on German soil. Further augmenting its German heritage, Can bassist Holger Czukay is a guest on the album!

- ARTIST: Devo

- ALBUM: Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!

- RECORDED: October 1977 and February 1978

- RELEASED: 1978

- LABEL: Warner Bros. Records / Virgin Records

- STYLE: New Wave, Post-Punk, Art Rock

In 1977, when Bowie, Iggy Pop, Robert Fripp and Eno were all stationed in Germany making some of the most influential music of their careers, Bowie and Pop received demos from an unsigned band called Devo, from Akron, Ohio. Bowie, Pop, Fripp and Eno all individually expressed interest in producing Devo’s debut album, with Bowie even proclaiming, “this is the band of the future, I’m going to produce them in Tokyo this winter.”

Japan ended up being Germany, and the lead producer ended up being Eno, with Bowie contributing additional production “during weekends,” when he wasn’t filming Just a Gigolo. Eno took a chance on the band, personally paying for their flights and studio time, confident that the currently unsigned band would soon sign a record contract. They mostly recorded in Plank’s Cologne studio, where Eno had recorded a few months prior with Cluster.

Devo and Eno did not gel in the studio. Despite having the alchemical genius of tried and true artist Eno at their disposal, for free, the fledgling band remained keen on sticking to the blueprint of their homemade demos. They later said, “we were overtly resistant to Eno’s ideas. He made up synth parts and really cool sounds for almost every part of the album, but we used them on three or four songs.” The clash of production ideas is no real surprise given how opposing their aesthetics were: Devo was exploring the idea of cold, angular, jerky, and mechanical, while Eno was exploring the idea of warm, flowing, atmospheric, and ethereal. Besides producing, Eno put his mark on the synths in “Space Junk” and “Shrivel Up,” and added distorted vocals to “Space Junk.” Although the process was not a meeting of minds, the ensuing debut studio album was “a seminal touchstone in the development of American new wave.”

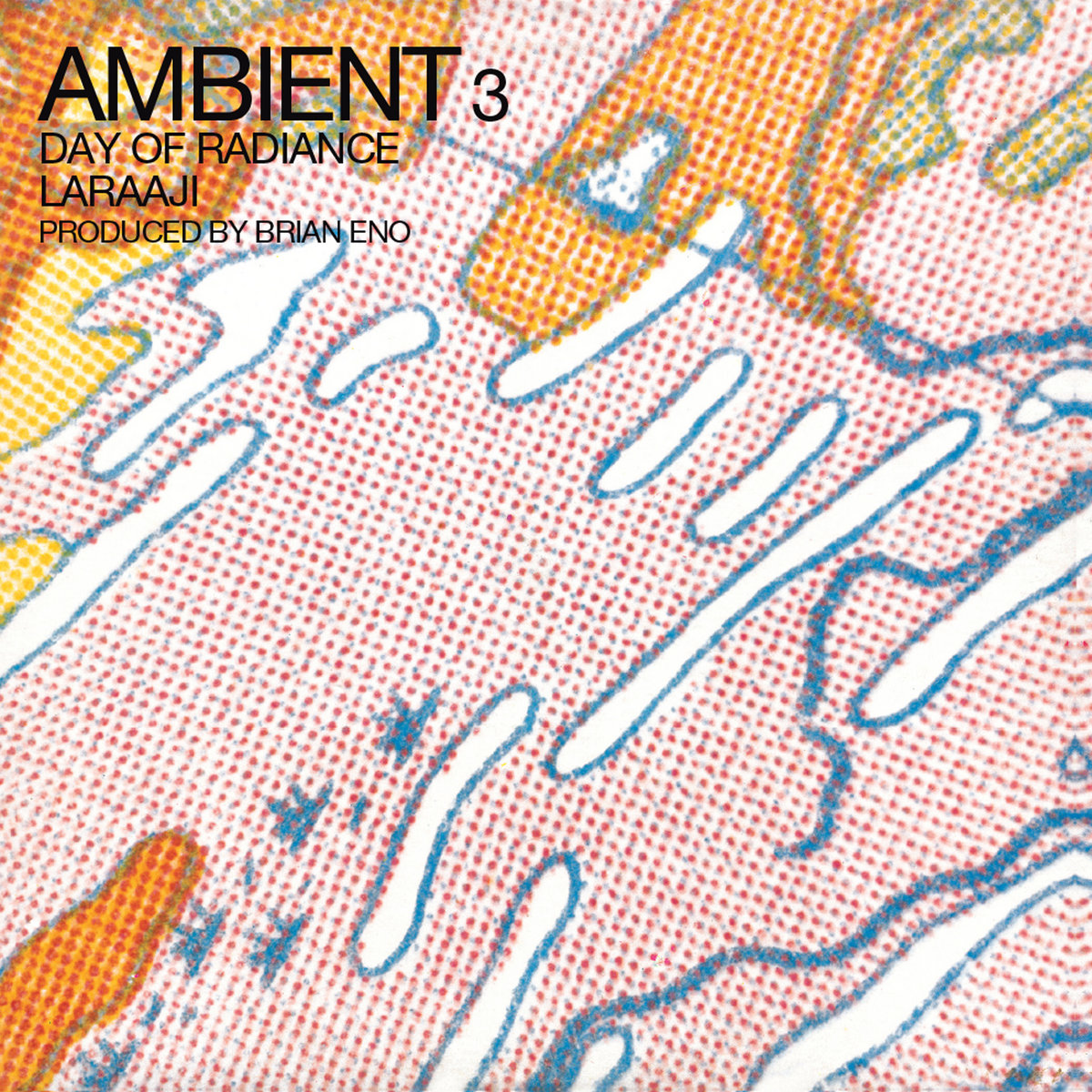

- ARTIST: Laraaji

- ALBUM: Ambient 3: Day of Radiance

- RECORDED: Unknown (sometime between 1979 and 1980)

- RELEASED: 1980

- LABEL: Editions EG

- STYLE: New Age, Ambient, World, Acoustic

Ambient 3: Day of Radiance, by American composer and zither master Laraaji, produced by Eno, is the third album in Eno’s Ambient Series (which launched with 1978’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports). This installment of the series has a different hue than others in the Ambient Series, mainly because of its dominance of organic instrumentation (e.g. hammered dulcimer and 36-stringed open-tuned zither) over electronics.

Laraaji and Eno seemed to have met through fate. In the 70’s, comedian-musician -mystic Edward Larry Gordon adopted the alias Laraaji, impulsively traded his guitar for a zither, modified the zither with an electronic component and busked the streets of NYC showcasing his unique sounding instrument. Eno, who was also living in NYC at the time, was on a walk when he stumbled upon Laraaji busking in the famous Washington Square Park, in lotus position, with his eyes closed.

In Laraaji Eno recognized a perfect talent to record with — someone guaranteed to be on his same wavelength. When Laraaji collected his money, he found a note signed from “Brian Eno,” a name that rang a bell. Just a month prior, while busking in the same park, a couple conversed with Laraaji, emphatically recommending that Laraaji check out Fripp and Eno. He recounted, “I wasn’t quite sure what they were saying; the name of an organisation. They kept saying ‘you should listen to this music.’ And that evening they invited me to their place and they kept on talking about Fripp & Eno. So I gathered that if I ever see the words Fripp & Eno again I’d move closer to it.”

A month later this mysterious “Eno” appeared in the flesh, absorbing Laraaji’s aura from afar — with Laraaji none the wiser. Laraaji recalled, “I didn’t get around to looking up the music at that time, and a month later, I received this note from Brian in my busking case and I thought ‘Wow, what a co-inky-dink’.”

Laraaji followed his word to “move closer” to Eno, and they joined forces for a highly unique album that would become a quintessential New Age album, and one of Laraaji’s most regarded works. From the layering of tracks to the repetitive loops to the electronic treatments and obscuring of the natural sound of the instruments, you can hear Eno’s presence throughout, but especially on the slower, more atmospheric B side.

… STAY TUNED FOR PART TWO!