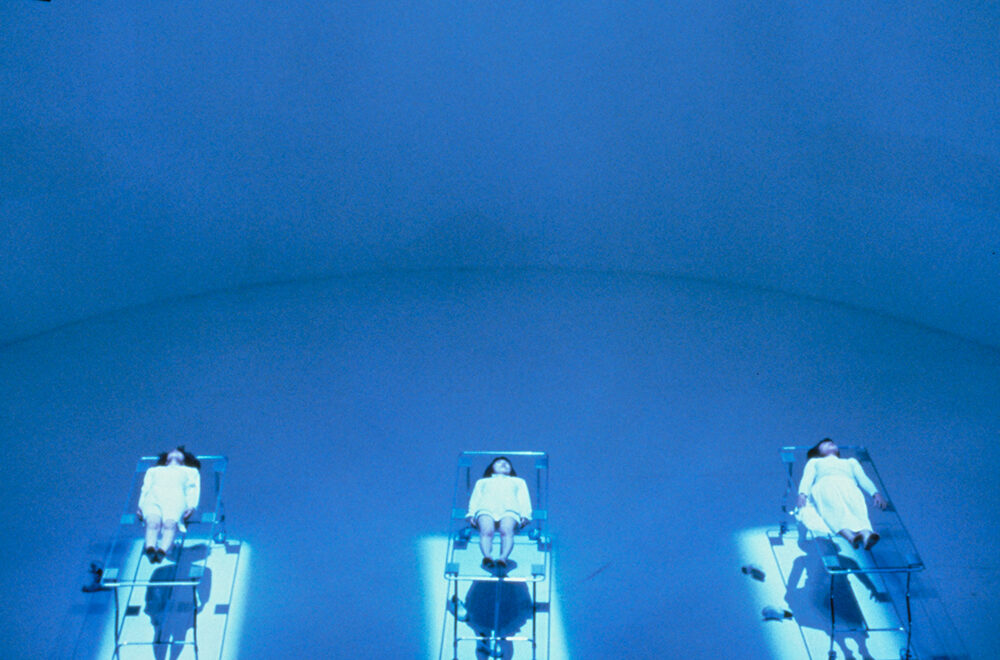

Two releases by the iconic Kyoto-based multimedia collective DUMB TYPE are available now through In Sheep’s Clothing distribution! For fans of Laurie Anderson, Robert Wilson’s “theater of images,” […]

Erik Satie: A Hundred Years of Not Fitting In

The composer’s music, and the life around it, was too still, too short, too strange — and now it feels like a blueprint.

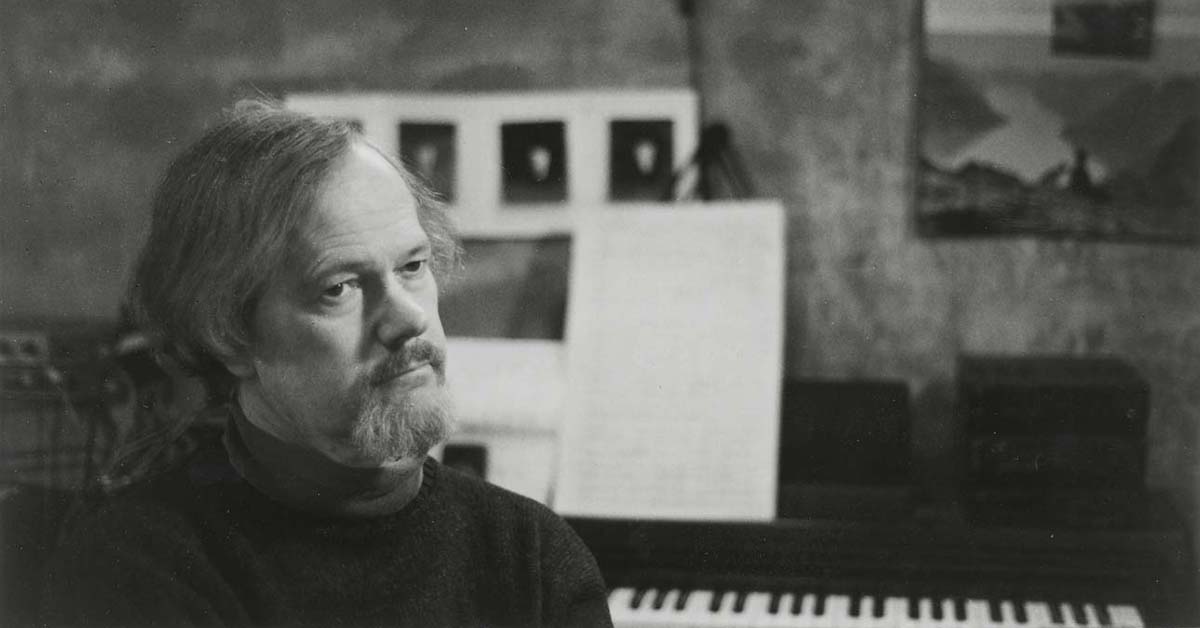

When we committed to reissuing Electric Satie, a one-off conceptual project by acclaimed Japanese electronic music producer Mitsuto Suzuki, it hadn’t tracked that the vinyl would land on the 100th anniversary of his death.

But across France, and far beyond, the milestone hasn’t gone unnoticed. This spring and summer have brought a quiet cascade of Satie tributes: radio retrospectives, museum exhibitions, piano marathons, and deep reappraisals. His former apartment in Arcueil, long the subject of local lore, was officially listed as a historic monument. And in a gesture he might have quietly applauded, a collective mounted an outdoor performance of Vexations, played in full on 18 upright pianos in a rotating overnight relay. Per Satie’s instruction, Vexations is a brief piece to be played 840 times in a row.

Join us this Friday as we celebrate the music of Erik Satie at the JACCC Japanese garden.

In the process, we’ve been swimming in Satie: reading tributes, revisiting recordings, digging into old interviews, essays, liner notes, reissues, and strange artifacts that keep surfacing in the current. The more we read, the less he resolves.

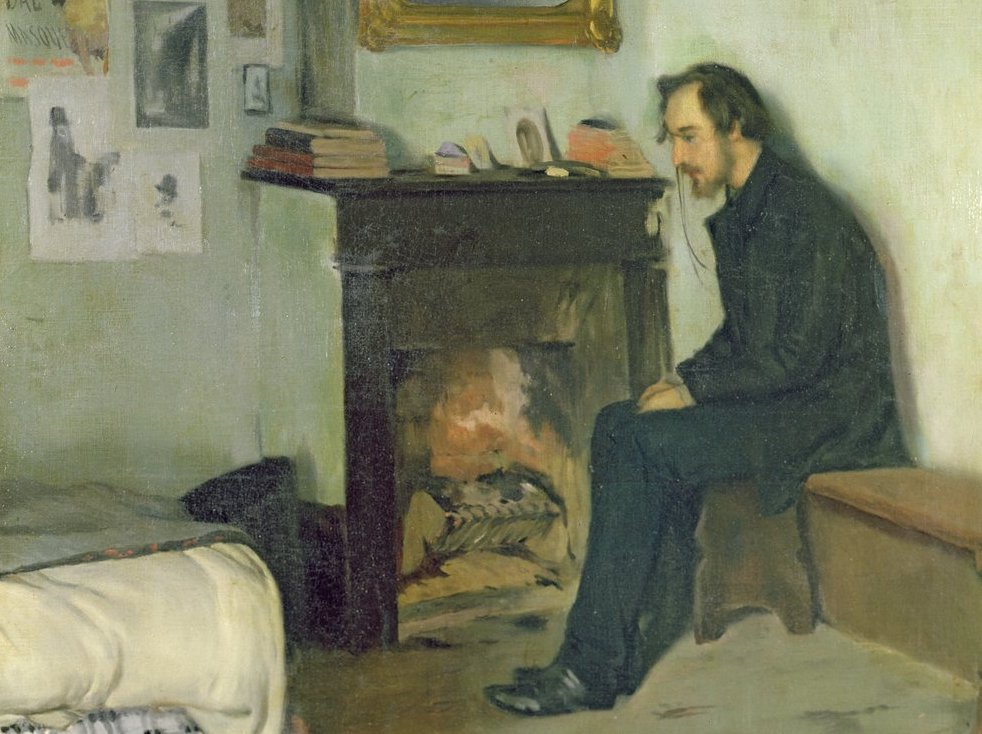

Satie was an odd duck. Almost exactly 100 years ago, just after his death, his friend Darius Milhaud visited that one-room apartment in Arcueil. Despite Satie’s renown, he had been living in near-total destitution, Milhaud wrote:

It seemed impossible that Satie had lived in such poverty. This man, whose faultlessly clean and correct dress made him look rather like a model civil servant, had literally nothing worth a franc to his name: a wretched bed, a table covered with the most unlikely objects, one chair and a half-empty wardrobe in which there were a dozen old-fashioned corduroy suits, brand new and absolutely identical. In each corner of the room there were piles of old newspapers, old hats and walking sticks. On the ancient, broken-down piano with its pedals tied up with string, there was a parcel whose postmark proved that it had been delivered several years before; he had merely torn a corner to see what it contained…

Satie cultivated simplicity, but his life was dense with contradiction. He wrote music meant to be ignored, then annotated it with obsessive performance notes. He championed minimalism and repetition, then buried personal meaning beneath layers of surrealist humor and deliberate confusion.

What’s striking, a century on, is how modern he still feels. Not just the “furniture music,” which now reads as proto-ambient, but the whole aesthetic: miniature forms, unadorned emotion, radical restraint. His sense of scale and silence. His refusal to behave.

What’s surfaced in the process isn’t a single unified portrait but a kind of echo chamber, one that reflects just how much Satie still frustrates attempts to pin him down. His life was structured but absurd. His music was modest but foundational. He could be precise, cryptic, blank, ecstatic, sly. And he still sounds strangely current, an artist whose contradictions feel less like puzzles to solve than conditions to live inside.

Here are a few recent moments that have stood out.

27 Lost Works Resurface, Performed by Alexandre Tharaud

In the early 20th century, Montmartre was raw at the edges: gritty, theatrical, thick with smoke and song. Beneath the absinthe haze and café gaslight, dancers, drunks, and dilettantes collided nightly in cramped cabarets. Satie earned his living there, not as a concert composer, but as a working pianist, hired to fill space while chaos unfolded. He drifted between venues like Le Chat Noir and Auberge du Clou, playing whatever the room required. The money wasn’t much. Neither was the glory. But the notebooks he kept, full of motifs, harmonic sketches and stray turns of phrase, tell another story. “Esquisses bitonales: No. 3” sounds an Aphex Twin meditation for piano.

On the occasion of his centenary, a striking, meditative collection of 27 previously unheard works has been brought to light. British musicologist James Nye and Japanese composer Sato Matsui spent years tracking down the pages, which had been scattered across archives including the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and assembling them into a coherent set. Many were written during Satie’s café years, when he walked miles between his sparse apartment in Arcueil and the city, jotting ideas as they came.

Alexandre Tharaud, a longtime Satie interpreter, performs the pieces on a new Erato release. The music is modest and oblique, often no more than a page, but unmistakably his. A newly discovered waltz, Valse inédite, floats like a half-remembered lullaby from a shuttered dancehall.

Satie’s Quiet Rituals

Satie didn’t perform his eccentricities. He lived them, precisely and without compromise. He owned seven identical corduroy suits, all velvet, all brown, and wore only those. He limited his diet to white foods — hard-boiled eggs, shredded coconut, bone marrow, rice — and rarely ate with others. He founded a church with himself as the sole member, wrote letters to nonexistent clergy, and filled its doctrine with absurd declarations. No one saw the inside of his apartment for years.

For decades, these details were treated as charming footnotes — oddities that reinforced his reputation as classical music’s great contrarian. But lately, a more reflective view has taken hold. Writers and musicians who’ve spent time with his work have begun to read his habits not as ornament but as structure. The rigidity, the isolation, the precise routines — they weren’t flourishes. They were boundaries. They made the world navigable, orderly, so that he may compose in peace.

He wrote pieces that ask almost nothing of the listener. You can tune in or drift past. But knowing the life he built around those sounds, it’s hard not to hear the deeper effort: to carve out space, to make something small and sturdy enough to stand inside.

The Vexing Vexations

In April, Marina Abramović and pianist Igor Levit staged a full performance of Erik Satie’s Vexations at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall. Billed as a sixteen-hour event, the piece was performed without spectacle or flourish, unfolding slowly and methodically as Levit repeated Satie’s brief, harmonically static motif just as the composer had suggested more than a century ago: “In order to play this motif 840 times in a row, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, in the deepest silence, through serious immobilities,” he wrote on the score. In Queen Elizabeth Hall, the performance space was arranged with soft lighting and cots for resting. Listeners came and went in near silence.

Written in the 1890s but unpublished during Satie’s lifetime, Vexations consists of a short bass figure and two variations. Satie never explained why he chose 840 repetitions. Over the years, performers have tried to decipher its tone — flat, austere, slightly dissonant — and its purpose. Is it a provocation? A joke? A kind of private monastic discipline disguised as a musical score?

Want to grab a copy of Electric Satie before it sells out? Grab it here.

On the centenary of Satie’s death, Vexations has returned in multiple settings. In Lyon, a collective staged a relay performance on 18 upright pianos over 24 hours. In Santander, 55 pianists took turns playing it straight through. But the Levit-Abramović version — slow, solo, unadorned — may come closest to what the piece suggests. Nothing changes. There is no progression. Just the same shape, repeated until meaning either arrives or disappears.

Stage Left: Parade, Socrate, and the Theater of the Absurd

This centenary has brought renewed attention to Satie’s theatrical works, particularly Parade and Socrate, two pieces that remain tough to classify, even now. Both have been revisited this year, not through lavish productions but through concert performances, new recordings, and small-scale tributes. On July 1, a chamber performance of Socrate was held in Carlisle Cathedral, one of several quiet nods to a piece that continues to haunt the margins of the repertoire.

Composed in 1918, Socrate sets fragments of Plato’s dialogues to a high voice and small ensemble, with almost no expressive coloration. The music moves without emphasis, stripped of vibrato or dynamic drama, as if Satie were trying to remove the composer entirely. What’s left is a kind of philosophical stillness—music that doesn’t build or resolve, only persists.

Parade, written two years earlier in collaboration with Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso, is chaotic where Socrate is spare. A surreal ballet packed with typewriters, sirens, megaphones, and non-sequiturs, Parade caused a scandal when it premiered in 1917 and still feels resistant to any tidy reading. Even now, it’s not clear whether it was meant as celebration or sabotage.

What ties both works together is their refusal to behave. Neither one unfolds according to musical logic or narrative expectation. Unlike Satie’s soothing proto-ambient music, the plays exist to disrupt, to disorient, and to outlast interpretation.

Want to grab a copy of Electric Satie before it sells out? Grab it here.