“Dubwise but not exactly dub, rich in ambience but not exactly ambient music.” With three of the classic Sade albums (Promise, Diamond Life, Stronger Than Pride) recently repressed […]

Finding The Soul of the 7″ Record

Tana Yonas explores the 7″ format with music writer Elizabeth Owuor and former Island Records exec Danny Holloway.

Many record collectors who focus on albums or 12-inch singles might find it a bit curious that others worship the 7-inch record. After all, most 7-inches come in generic blank sleeves and each side holds a mere three to five minutes of music, which might make it seem like you’re getting robbed of the pleasure of the long-playing experience. But the deep subculture around 7-inches continues to grow, change and adapt, which makes sense. After all, it’s played a big role in the history of recorded music.

Like any journey worth embarking on, to find the soul of the 7-inch it’s best to start the conversation with those “in the know.” For this piece, we’re guided by two experts of the format: Elizabeth Owuor, a DJ, music writer and co-founder of the popular monthly rhythm & blues party “Black Rhythm Happening”; and Ximeno Records owner and DJ Danny Holloway. Holloway’s fascinating career in music ranges from record producer for Island Records to journalist for NME. His Ximeno Records exclusively presses 7-inch records, so his love for the format is obvious.

This story starts with the jukebox. The record industry experienced a rebirth after the depression in part because of the machine, which was an inherently social invention. “The jukebox was found in bars and other social environments, so they needed a format that was loud — that could be played in spaces where people were talking and dancing,” says Owuor. Seven-inches are generally pressed louder than LPs, and were meant to create a lively atmosphere. Owuor says that this is why DJing 45s are so fun: “They provide a covenant or compact with the dance floor.”

Jukeboxes are also the reason the 7-inch has such a large hole in its center (and why you now need that 7-inch adapter): To fit it in the jukebox’s sorting mechanism.

Small independent labels started to pop up all over the country in the 1950s. The result? Labels, Holloway says, “could promote their records via jukeboxes and bars a lot more cheaply than they could by trying to get it on the radio. Back then, you kind of had to pay people money or something in order to entice them to play your music — no matter how good it was.” The format also freed labels and artists from the pressure of conceptualizing and recording full albums, so for many artists the 7-inch was the key to drawing a fanbase.

The format was also used to promote records with the new concept of a “single,” adds Owuor. “The whole concept of singles and singles charts like Billboard exist, in part, due to the influence of the 45. And our intense fascination with songs presented as singles is related to the compactness of the format. Forty-fives inspire an intense focus.” Added Owuor: “There is a correlation between this medium, which is super compact and the single. Narratively, it’s very tight, and something about the 45 inspires a certain type of fanaticism. That goes for every 45 record kid out there who loves the format. It forces you to focus on one particular song or idea.”

She cites an example: Larry Williams 1953 song “Dizzy Miss Lizzy,” where her DJ name comes from. “That singular focus moves you to ask, ‘Who was Larry Williams?’ and ‘Who is this Dizzy Miss Lizzy he speaks of?’ It enrolls you in the narrative in a different way.”

Often labels pressed what they hoped would be a hit on the A-side, and include a ballad on the other side — or what they thought was a forgettable track. They wanted to keep the focus on the song they were promoting, which is one reason why celebrating the “B-side” is popular in the 7-inch culture. Holloway explains: “Part of the overall attraction for people that collect 45s is the fact that there’s a lot of weird things on B-sides. There’s what they call non-LP B-sides because you can’t get the song anywhere else but on the B-side of that 45.”

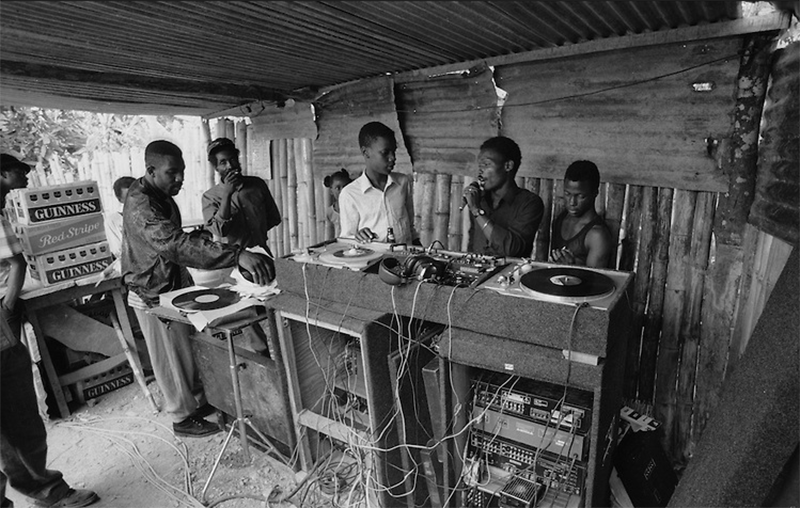

Though the format means different things to different cultures, nowhere was it more popular than Jamaica. In the 1950s, most records in the country were pressed with kitschy calypso music for visiting American tourists. In an economically depressed Kingston, few residents had electricity, let alone could afford to buy records or players themselves. Because of this, live and recorded music was experienced mostly in communal settings around mobile entertainment centers known as sound systems. There was fierce competition among the sound system DJ “selectors.” The movement pushed local studios to churn out new records quicker and quicker to win the sonic battles between DJs who claimed to have the best selections in the city.

As the economy and infrastructure improved, some local labels and sound systems started pressing cheap 45s to sell alongside the sets — which in turn created a hunger for buying new music. These early recordings often featured local artists adapting early American rhythms. Even the young Bob Marley’s first songs followed the tradition of the jazz-injected shuffle-beat rhythms of ska: the Jamaican amalgam of American rhythm & blues and native folk-calypso called mento.

Holloway first went to Jamaica in December 1972. Once he arrived he “saw that it was almost all about the 7-inch. There wasn’t too much else and they were making 12-inches in the 70s for export only. I remember going into record stores and seeing a stack of 12-inches of a certain tune that I wanted, and they wouldn’t sell it to me. They had strict rules that 12-inches were for export only. I even tried to bribe them, they’d go, ‘No, no, no, can’t do it. We can’t do it.’ It was all about the 45.”

But something else makes the format so attractive to so many people, says Owuor. “It provides a sense of tactile joy, and totally connects you to the power of the music in a very physical way. There is a connection to me between touching this very beautifully compact object, putting it on the turntables, having people dance and then having to repeat that again and again after just a couple of minutes.”

She adds, “In fact, it’s like Russian roulette for me. My adrenaline definitely increases when I’m interacting with a 45 in a way that LPs don’t—and it’s been a renegade format from its inception.” Holloway had some practical reasons: “If you’re a current DJ and somebody says, ‘Hey man, come out and spin a three-hour set,” you could take a couple of small boxes of 45 and carry them no problem. If you want to do the same thing with 12-inches, then you’re probably carrying two or three crates, and it’s heavy so you need to factor it in.

To Owuor it’s “the little engine that could. It was like the overlooked cousin of the LP, and then it rose to prominence — especially in correlation to rhythm & blues music. From rhythm & blues it went on to rock & roll and punk and other genres. It is associated with youth culture from there. By its very nature it’s a renegade outsider format.”

And because the 7-inch was louder and more affordable, it was always associated with youth culture. It’s not a leap to connect why genres with loud and fast rhymes flocked to the format. “Any kind of really loud music that has a short narrative is really, really ideal for 45.”

Owuor notes, though, that “there are contradictions too, because the 45 was created as a mass-market commodity, but people in these rare record communities spend hundreds or thousands of dollars on it.” She calls it “a really interesting contradiction.”

Hollaway adds that collectors prefer these expensive or poorly pressed or damaged originals because “if they purchase it on a reissue label, it is not admired in the same way. If you have the original release, and you paid $180 for it, then you’re given props even if the quality isn’t great.” Holloway’s Ximeno records reissues a whole catalog of old records. For him, the quality is paramount, one reason why they win over veterans to the scene.

Rarities? Of course. The most expensive 7-inch is a Motown/northern soul 45 called “Do I Love You (Indeed I Do)”, recorded by Frank Wilson in 1965. This record sold for over £25,000 ($31,000) at auction in 2009. It’s collectible because it was Wilson’s only single and the majority of demo copies were destroyed.

For Owuor, “the 45, represents so much beauty, not only aurally but physically, at a tactile level. I love how beautifully compact it is. It’s that covenant with the dance floor. As a rhythm & blues 45 DJ, it’s music that was made to make people move. It’s so satisfying.”

Follow Ximeno Records: https://www.instagram.com/ximenorecords

Follow Black Rhythm Happening: https://www.instagram.com/blackrhythmhappening/