The summer is halfway over and you’ve been scrolling for like, what, six weeks straight now? Step away from your phone (after reading this, of course). An analog […]

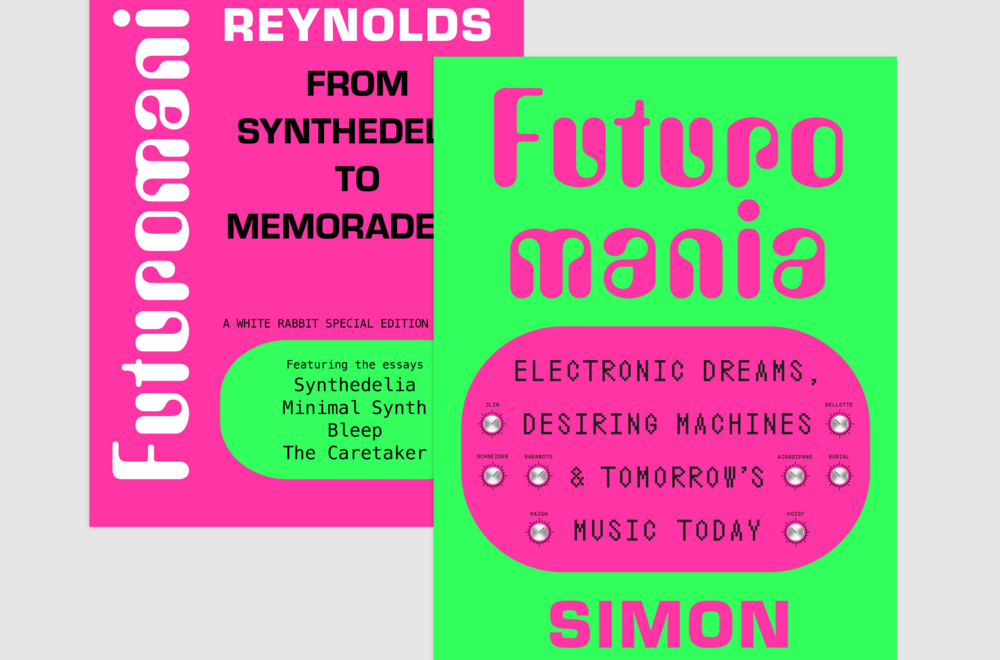

Read this: Simon Reynolds’ ‘Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture’

The best book on the rise of electronic dance music turns 25 next year.

The introduction to Simon Reynolds’ essential book Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture, contains a confession from the great L.A.-based culture writer. Growing up in the post-punk 1980s, he wasn’t a club kid, he writes:

[M]y take on dance music was fundamentally rockist, in so far as I had never really engaged with the music‘s original milieu – clubs. This was perhaps forgivable, given that 80s “style culture” dominated London clubland. Its posing and door policies, go-go imports, and vintage funk obscurities were anathema to my vision of a resurrected psychedelia, a Dionysian cult of oblivion.

Then, he continues, he had an epiphany.

Little did I realize that just around the corner loomed a psychedelic dance culture, that the instruments and timespace coordinates of the neo psychedelic resurgence would not be wah-wah petals and Detroit 1969, but Roland 303 bass machines and Detroit/Chicago 1987.

Within a few breathtakingly well written paragraphs, Reynolds captures the epiphany of falling in love with dance culture, a sensation that many who came of age in the 1980s and ‘90s similarly experienced when passing the threshold into their first warehouse parties and raves.

It was some revelation to experience this music in its proper context – as a component in a system. It was an entirely different and unrock way of using music: the anthemic track rather than the album, the total flow of the DJs mix, the alternative media of pirate radio and specialist record stores, music as a synergistic partner with drugs, and the whole magic/tragic cycle of living for the weekend and paying for it with the midweek comedown.

Across the next 19 chapters, Reynolds – who grew up in London and earned his earliest writing gigs at British music weekly Melody Maker before expanding internationally through work in the New York Times, The Wire, Village Voice and the Los Angeles Times – digs into the seeds that planted dance culture and explores the many subgenre offshoots that sprouted in London, Detroit, Chicago, Ibitha and elsewhere across the years.

The chapter subtitles offer a sense of the book’s breadth:

Detroit Techno, Chicago House, and the New York Garage, 1980-’90. Sampling and the Soundscape. Acid House and UK Rave, 1987-’89. Spiral Tribe and the Crusty-Raver Movement. Rave as Counterculture and Spiritual Revolution. Jungle Takes Over London, 1993-94.. American Rave’s Descent Into the Dark Side, 1993-97, among many others.

Watch: https://youtu.be/ZclaXQWVRCg

With each flip of the page comes fascinating facts and ephemera from the era. Here he is on acid house in 1988:

“The acid house revelers often compared the feeling in the summer of ‘88 to punk rock,” writes Reynolds of England’s so-called Summer of Love era of the late ‘80s, describing “the same explosion of suppressed energies, the same overnight Year Zero transformation of tastes and values. All that was missing was the mass media’s discovery of the new subculture and the inevitable moral panic over what the kids of today were up to.”

Of the mid-1990s rise of IDM, a.k.a. intelligent dance music, through labels such as Warp and Reflex, Reynolds says this:

For all its rhetoric of progression, intelligent techno involved a full scale retreat from the most radically post human and hedonistically functional aspects of rave music toward more traditional ideas about creativity, namely the Artur theory of the solitary genius who humanizes technology rather than Subordinating himself to the drug – tech interface. There was even a resurgence of rock notions like the concept album and live musicianship, with bands like underworld and orbital developing new forms of onstage improvisation based on the live mixing of pre-recorded, sequenced parts.

His writing on drum & bass, breakbeats and jungle goes deep, connecting Africa and academia, serialism and synth rhythms.

This rhythm-as-melody aesthetic recalls west African music. It also parallels the preoccupations of avant classical composers like John Cage and Steve Reich, who drew inspiration from the treasure trove of chiming timbers generated by Indonesian gamelan percussion orchestras. Jungle fulfills the prophecy in Cage’s “Goal: New Music, New Dance” of a future form of electronic percussion music made by and for dancers. “What we can’t do ourselves will be done by machines and electrical instruments which we will invent,” Wrote Cage, seemingly predicting the sampler and sequencer.

An essential addition to every music lover’s library, “Generation Ecstasy” remains the best book about the birth and rise of electronic dance music.