The summer is halfway over and you’ve been scrolling for like, what, six weeks straight now? Step away from your phone (after reading this, of course). An analog […]

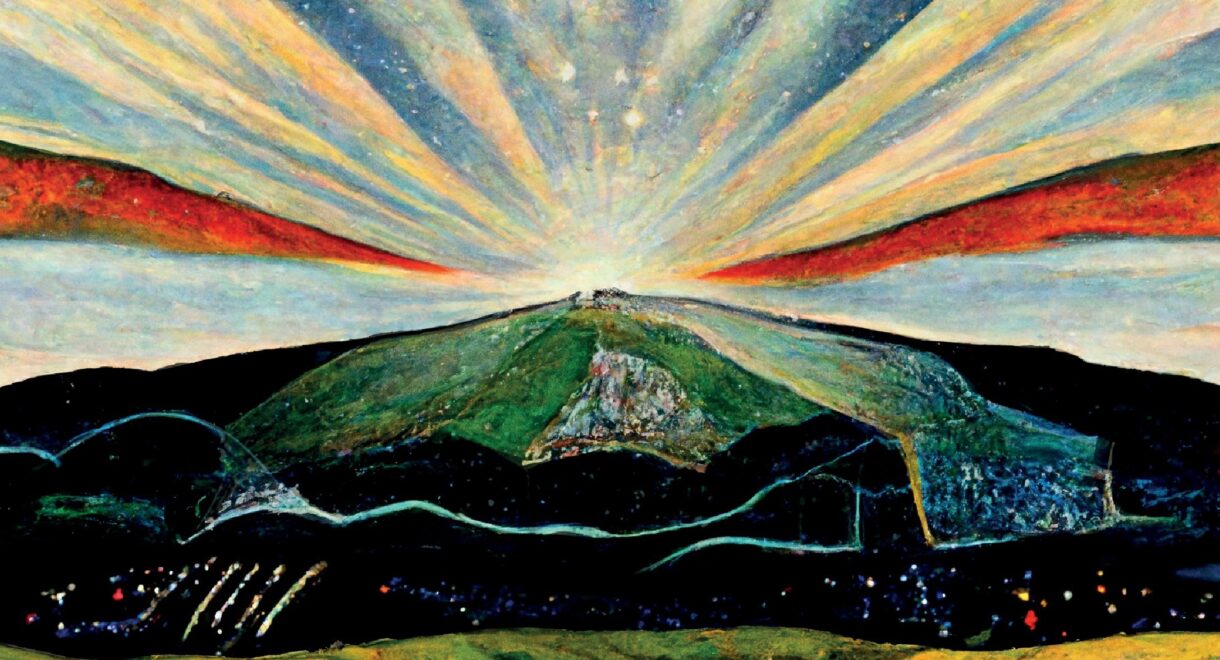

Holding on to Darkness: Healing Through the Sustained Drones of Sunn O)))

Marty Sartini Garner reflects on the healing power of ambient and metal during darkened times.

The first new album I fell in love with in 2020 was Leo Takami’s Felis Catus and Silence, a gentle, opalescent jazz guitar record in the tradition of Windham Hill and Studio Ghibli. The last record I fell in love with was Necrot’s Mortal, a brutal death metal album whose cover is an illustration of a person who has removed their own skin with a scythe and is holding it up for the viewer to see; the defiance on their face is plain, despite the missing eyeballs. The music—thrashing, wailing, full of force, like watching a sea of ball bearings churn and tumble—feels the same way.

It’s banal to say that the last year affected profound change on all of us here in the United States, but that doesn’t make it any less true. At times the past ten months have felt like they’ve brought a series of revelations about who we are, both socially and individually. And yet those changes can be hard to see when so little in our environment changes from day to day. Contrast is basically impossible to find. Hours pass by in a fog of collapsed time, only to be shaken violently into the present by some new terror. The more the shaking continues, the more the brutality of it fades, and you find yourself in a new, denser fog.

Perhaps that’s dark. I mean to make it dark. It’s been a dark time. And the longer the pandemic endures, the time in which incredible confusion clings to razor-sharp clarity like steam on a glacier, dark it will stay. This is why I can’t stop listening to metal.

For someone who typically favors transcendental jazz and citrus-toned grooves, and who is still dealing with the shame of having grown up a Limp Bizkit fan, this is something of a foundational shift. Had I been told in advance what 2020 would have in store, my bet would have been that I would spend my time with new releases by Green-House, Iceblink, Emily Sprague, Ana Roxane, Omni Gardens—people whose music points to healing and forms of optimism as artistically enriching and sources of great emotional peace. This is one of my greatest and most hard-won convictions: There is more truth and resonance and depth in positivity and joy than there is in the cynicism that passes for realism.

And yet, as the year clicked along and the state of what we found ourselves in became more apparent, I often lost the taste for these sounds, or perhaps I lost the specific kind of attention they require.

GrimmRobes Live is as textured and sustaining as Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Music for Nine Postcards; like so much of the healing music whose values I love and affirm, it holds me aloft.

When I needed to quiet my mind, I found myself turning instead to Sunn O))). With headphones on, I’d let the guttural exhale of Stephen O’Malley’s guitar and Greg Anderson’s bass flood my consciousness, blasting through me so loudly I could practically taste the pebbled leather of their amplifiers. Over the past two decades, O’Malley and Anderson haven’t tamed the staggering noise they produce, but they’ve influenced its direction, resulting in a greater range of sound than the rages of their early music might have suggested possible. And while I’m not immune to the orchestrated power and broad palette of Monoliths & Dimensions or 2018’s Life Metal, the 2008 recording (初心) GrimmRobes Live 101008, recorded at L.A.’s Regent Theatre on the tenth anniversary of their debut, GrimmRobes Demos, is the version of Sunn O))) that some freshly awoken part of me craves. Across 90 minutes, their two instruments drone in long, ugly waves that never crest, their lowest undulations testing the bottom limit of the mics. Though it goes nowhere in particular, it’s almost purely physical music, meant to be experienced in the body instead of the head. It asks a lot of you: patience, the ability to withstand prolonged abrasion. The point is simply to abide…

GrimmRobes Live is as textured and sustaining as Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Music for Nine Postcards; like so much of the healing music whose values I love and affirm, it holds me aloft. But healing music, I’ve realized, reminds me of the need to heal. And what did it mean to heal in 2020? To come to terms with the unrelenting carnage of the COVID–19 pandemic? To no longer feel the urgent press of racial protest? To be free from the effects of the intense corruption and attendant collapse of our political institutions? Is it acceptable to want not to feel the brutality of the era? Or would healing mean feeling these things in their true intensity? These are the questions—the tensions—that roll through me every day. Often I’m not aware of them; often I’m privileged enough to feel good, cheerful, playful. But they are there.

So frequently I didn’t want to see the pain and confusion that gird everyday life. But, for perhaps the first time in my adult life, I really wanted to feel both. Feeling—taking the darkness into my body, or dredging it up from within me—seemed like the only proper response.

Kannon, Sunn O)))’s 2015 album, was shaped by O’Malley and Anderson to be a kind of sonic relief; the title refers to the Buddhist transformation of suffering into compassion. Its three grainy drones remind me of a tub I used at an onsen in Kyoto that shot an electric current through the water. It gave me a bewildering and terrifying and ultimately pleasurable buzz to stand there, in the presence of danger with the assurance of safety, and think, I’m not supposed to feel like this, but I do. The steadiness of Kannon allows me to soak long enough for the first part of that sentence to fizz into nothing, until it’s simply an affirmation: I feel this way.

I keep going back to Sunn O))), and to the brutality of a single chord being allowed to decay.

These two sentiments—I’m not supposed to feel this way and I feel this way—are difficult to separate, but it feels increasingly urgent to try, and the physical power of black metal makes the effort more manageable. Pushed along by the sheer melancholy force of Silver Knife’s self-titled album, I found myself agog at how the bleak can always get bleaker. The deeper I wandered into Afsky’s Ofte Jeg Drømmer Mig Død or Death’s classic Human, lost in a thicket of riffs and blast beats, with only occasional scraps of discernible vocals lighting the way, the more able I felt to say, simply, This is how I feel, regardless of how I felt about that This.

Literary theorist Terry Eagleton says the sublime is “the most typical of all aesthetic moods, allowing us as it does to contemplate hostile objects with absolute equanimity.” Black metal functions this way, though perhaps contemplate is too heady a word. Indeed, in a world gone increasingly gnostic, black metal is an ironic icon for the goodness of incarnation, a reminder of how it feels to inhabit a body. Following Tomb Mold as they leap from riff to riff in a song like “Beg for Life” can at times feel like listening to Ornette Coleman’s double quintet: It’s brutal, but it’s not monotonous. It moves with its own internal logic, and. Once you learn how to ride the bucking ghost that lives at the center of all this static, you realize how supportive it feels: You’re taken for a ride, but you won’t be thrown off.

To feel the sublimity of black metal requires a tacit admission of weakness; you have to be willing to acknowledge, even quietly, that you’re staring at something bigger, uglier, and more powerful than you are.

We live in a terrifying and confusing age. Whole days pass where things feel normal, sometimes even good. And some days feel as though they’re perched on the edge of an abyss. It’s amazing how wide the tear in the seam of what was once reality has become, and how on the days when it’s stitched up you can’t even see it.

I keep going back to Sunn O))), and to the brutality of a single chord being allowed to decay, how O’Malley and Anderson’s shrieking amps and effects keep that tangle of notes ringing for so much longer than its natural lifespan would dictate, and to the violence of allowing its frequencies to scream until they no longer cohere. Those rippling frequencies are the sound of what was once the known and apparently natural world being shredded, so that whatever’s next might become visible. Nearly all music is the sound of death and resurrection, of chords that attack and then decay and ultimately give life. Maybe Sunn O))) is just more transparent about the whole thing. Or maybe there’s mercy in the sustain pedal.

To feel the sublimity of black metal requires a tacit admission of weakness; you have to be willing to acknowledge, even quietly, that you’re staring at something bigger, uglier, and more powerful than you are. And that in itself feels like a form of progress—a way of knowing one’s own limitations more honestly. In this brutalizing, no-bullshit time, listening to it has helped me to peel away the skin that I’ve worn for so much of my adulthood. From the safety of my square-walled bedroom, I hold it up, and I look out, unsure of what to do next. Maybe I’m still recognizable to myself, maybe I’m not. It’s difficult to see. But I feel so much more.