Gelareh Khoie shares the story of thirtyninehotel, a legendary nightclub, art gallery, and performance space powered by Klipschorns from David Mancuso’s Prince Street loft parties. Love (Art & […]

In Conversation: A New Era of Audiophile Jazz with Blue Note’s ‘Tone Poet’ Joe Harley

Tana Yonas speaks to Blue Note’s Joe Harley on his history with jazz and the upcoming releases in their Tone Poet hi-fi series.

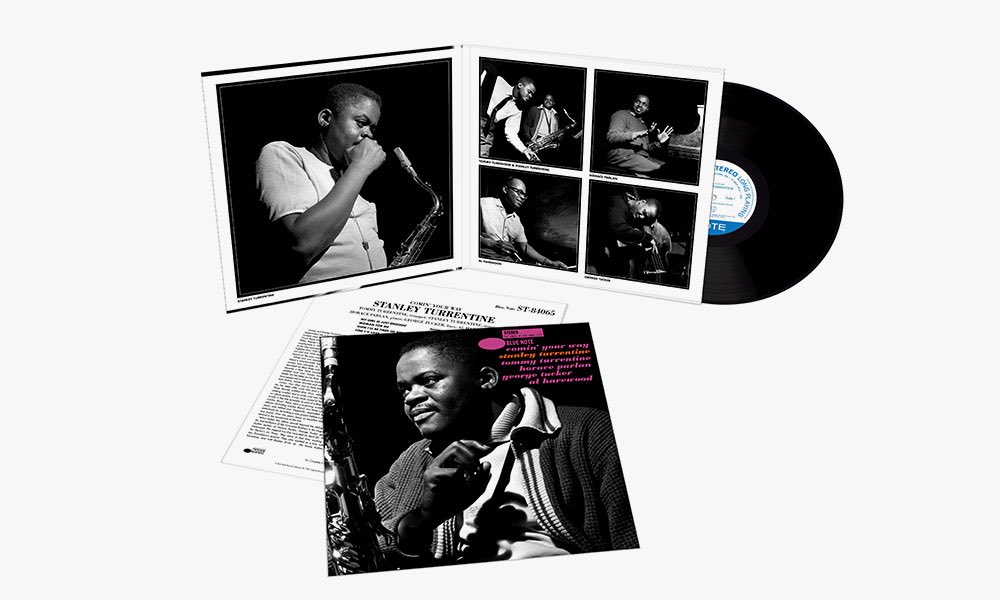

Blue Note’s recent Tone Poet reissue series has stunned fans with picks from their historic catalog, which stretches back to 1939. The magician behind the revival and remastering of these original session tapes is the “Tone Poet” himself, Joe Harley. Together he and his team have helped shepherd in a new age of jazz home listening.

Surprisingly, this is the first “hi-fi” project for Blue Note and they make the claim that you’ll never get a better version — original pressing or otherwise. The aim of the series is to fully honor these sessions of well- and lesser-known artists, including Chick Corea, Hank Mobley and Donald Byrd, and to sonically bring fans into the studio.

To the delight of fans, Blue Note has just announced their releases for 2021-2022, the first of which comes out March 12th. It’s from Charles Lloyd, who happens to be who gave Harley his now famous “Tone Poet” nickname, and the namesake of the series. The full schedule of releases can be found at the end of this interview.

What was your initial introduction to Blue Note?

Well, I was a kid in Lincoln, Nebraska, not exactly a hotbed of jazz, but my mother listened to a lot of it at home. I got fascinated, particularly with the drummers, because I was playing drums as a little kid. And when I started to hear people like Philly Joe Jones and Art Blakey, it blew my mind because I didn’t know what they were doing. But I learned. I went to the library and found some old Downbeat magazines and I started to look through them.

When I was about 10, I rode my bicycle down to my local record store and started looking at the jazz section. And to this day, I still don’t know how a store in Lincoln, Nebraska had original Blue Notes. We’re talking 1961, but there they were. I don’t remember the other titles, but they had Sonny Clark’s Cool Struttin, and I recognized the name of the drummer because I’d seen his name in Downbeat, Philly Joe Jones. And then to be totally honest the cover was what really drew me in. I was old enough to know that cool was desirable, and so I thought, “All right, this looks fantastic, plus it’s got those legs on the cover.” And so I took my allowance money and bought the record and raced home on my bicycle; that was my first ever Blue Note record.

I still remember looking at the logo with it’s blue and white motif. I still remember staring at it thinking how cool it was. Then, when I put the record on, I was hooked. I sat there with my little Ludwig drum set and my headphones trying to play along with Philly Joe Jones. It wasn’t pretty, let me tell you, but the hook was set and I couldn’t get enough after that.

I really love that story because you talk about the physicality of the record. It's not just a sound but it's the name of the players, it's the feeling of the sleeve; It's a visceral physical experience. I know that was also extremely important to you for the Tone Poet series, how did it fit into this project?

That’s a great question. Before we started the programming for Tone Poet, Don Was, President of Blue Note, was very aware of its importance. I had started along with my friend, Ron Ronbock, to re-issue a Blue Note series for the label Music Matters. We did over a hundred titles and we made the decision very early on that we wanted to try to bring whoever bought those records into the event — give them an idea of what might it have been like to be there. So we did that by breaking the normal mold, which would be to do an exact copy of the original. The originals weren’t gatefolds, by and large, and they didn’t have session photos inside.

We knew there were photos by Francis Wolff, who was the other partner in Blue Note along with Alfred Lion. Those two guys founded Blue Note in 1939. Francis was an avid photographer, and lucky for us he took his Nikon camera to almost all the sessions and shot photos. So knowing that we could get a hold of all those photos, we made an arrangement where we could use them in our releases.

I knew it’d be successful, but did I understand the degree? No. People loved having something where they knew all aspects of the production were done as they should be.

And as far as the presentation, we wanted them to be the best album jacket that could be made and present the music in a way that made it more of an event. The package was nice: the cardboard, the texture, you could feel their old style. They’re called tip-on jackets and it’s the way jackets used to be made. We put session photos on the inside of the gatefold and the specialness of that attention to detail reflected the attention paid to the mastering and all aspects of the production. It was evident from the minute you pick up the record that it was special.

It’s incredible that this all happened before the Tone Poet Series. What was that first conversation like with Don Was when he introduced the concept to you?

Well, Don and I were at EastWest Studios in Hollywood working with Charles Lloyd, a great artist. Don pulled me aside one day and said, “I’d really like to do something like what you and Ron are doing at Music Matters. I’d like you to do it for us. Would you be interested?” And my first thought was they’d never do it because it’s really expensive. You know, the jackets are expensive, the mastering, everything about it is a little more costly and consequently, you have to charge more. So I just figured it’d be very short, “Yeah, it’s a great idea, but here’s what you’re looking at,” and that would be the end of it. I explained all that to him and he just got this great big grin and he went, “Fantastic.” And so all my defenses were gone and I thought, “Well, if you’re down for that, then I’m down, too.”

The way we went, there was some planning and I had to come up with lists of titles. There were some new vendors that Blue Note had to start using and we had to establish those contacts. Anyway, all of that got done, and half a year or so later we were off and running.

What was it like to walk into the Blue Note vaults with all of the master tapes for the first time?

I get the shivers even thinking about it. You see all the history of jazz sitting there on those shelves. By that time we had done so many Blue Note reissues with Music Matters so I held a lot of those master tapes. But to see them in one spot is just an amazing thing; kind of overwhelming and emotional, in a great way.

This was the first HiFi project for Blue Note, so I’m curious, how do you define the term “audiophile”?

I think one way to look at it is a quest for perfection, which we can never quite attain. What I mean by that is, the word at its best is a desire to bring the studio or live performance into your listening room. In the case of a symphony, AC/DC, or Megadeth or something like that, could you really have that in your living room? Probably not. The authorities would probably show up at some point. But in the case of smaller-scale music like jazz, with the right gear you can come pretty close to recreating the event. Can you ever completely pull off the magic trick? No, and that’s where some of the madness of it comes, because you can get closer and closer, but you never quite achieve a hologram.

Although sonically, if your setup is correct you get what audiophiles referred to as “stage imaging,” If everything is placed properly, you get a complete sort of three-dimensional soundstage. If you listen in the dark or you close your eyes, it’s awfully close and awfully compelling. That might be audiophilia at its best, and that desire at its worst. Sometimes it just becomes hardware worship. And I’ve known audiophiles that have half-a-million dollar setup and 100 records that they play over and over and over again. So then it can become something more akin to listening to the gear rather than listening to the music. So you know there can be good parts to it, and parts that are maybe not quite so healthy, although nobody’s we’re not hurting anybody. There are worse addictions to have.

What is your ideal home listening setup like in regards to gear?

Well, the speakers I use are Vandersteen Model Sevens, the phono stage and preamp are from Audio Research and the amplifiers are the Ayre Acoustics MX-R power amplifier. The turntables are pretty wild. It’s called the Transcendence and is made by Basis. This stuff is collectively pretty pricey, but the great thing about analog is you can spend a really modest amount of money and hear all the reasons why people get excited by analog.

There’s a whole movement, which I know you guys are into, for vintage gear. You can get vintage gear that’s affordable and incredible. You can spend a fortune or you can spend a little, but basically if it’s totally honest and you set it up correctly in your room, I tell people, you can do alot with very little. One sort of handy rule of thumb for speaker setup is to think of it as you’re sitting at the center of an equilateral triangle. You can’t go too far wrong with that.

Many of those million-dollar systems I wouldn’t give you a nickel for. They can narrow what you want to hear until you can only really play 20 records because the rest of your records sound bad. So you end up not wanting to listen to them. I don’t like gear like that. I want gear that makes me want to hear everything I’ve got.

I get the distinct impression that In Sheep’s Clothing has a similar sort of view. That it’s really about enjoyment and satisfying the soul and not just worship of gear.

Was the Tone Poet series meant to be a long-term project? Were you surprised at the success?

I’ve never really asked Don Was and the others, but I got that impression. When we first started, we were going to try it and see and so initially we agreed to one year.

And I know there were people within the organization that thought, “$35 bucks, who’s going to spend $35 bucks on an album? What, are you guys crazy?” And so initially when we started, the numbers that were ordered from the pressing plant and from the printing company were pretty modest. And I remember when we released the first two records, I got a phone call from Justin Seltzer at Blue Note and he said, “Well, we have a problem.” And I thought, “Gosh, you know, first records out, and so I guess this is it. I guess something’s really wrong”. But then he continues with, “Yeah, we have a problem. We’ve sold all the records and we haven’t even shipped yet.”

Historically though, Blue Note introduced so many things in the history of modern jazz. Like Thelonious Monk, his first records were for Blue Note. Nobody would touch him because he was considered commercially a non-entity… They knew it was important.

And I thought, “Oh, well, that’s a good problem to have. It’s a problem, no doubt about it. It’s better than nobody wants them”. And so for a few release cycles, they kept increasing the numbers ordered and they were never enough. It was like they were kind of dipping their toe in and they kept selling out. It took six or seven months for everyone to kind of understand this is how these things are going to be received. We have an understanding on quantity now, but it’s an ongoing challenge. We’ve got our pressing plant almost maxed out.

I knew it’d be successful, but did I understand the degree? No. People loved having something where they knew all aspects of the production were done as they should be. In other words, they knew who mastered it, they knew that we were using the original masters and they knew that the presentation, in terms of packaging, was going to be as good as you can get.

Do you feel like it’s important for listeners to know the history of the original engineer, Rudy van Gelder? His mastering style was so unique.

Yeah, I think one of the real important things to know is that in the heyday in the 1950/60s period of Blue Note, Rudy started working with the label, I believe, in 1953. But all throughout until maybe ‘68 or ‘69, Rudy was recording live to two-track. What that means is that you’re mixing on the fly as that session is going down. It’s really hard to do. There’s no punch-in or fix it in the mix later. That’s not possible when it’s live to two tracks. The mix that he’s doing, as the guys are playing is the mix you’re going to get. That’s what you work with.

So if Lee Morgan steps up to the microphone and he’s a little close, there might be a little overload and you can hear Rudy diving for the fader to make his adjustment. If you’re after multitrack precision and perfection, you’re not going to get that with Rudy van Gelder recordings. He comes really close though. It’s shocking how good he was, but to me, that’s part of the excitement, too. You can hear him working to get it all in there and contain it.

And there are Art Blakey sessions where Art comes thundering in on drums overloads the mics, and that’s actually kind of exciting too. You hear Rudy trying his best to make his adjustments and it’s all there on the master tape. So yeah, there have been times over the years where customers will say, “On track two side B, at two minutes and 31 seconds in, I hear what sounds like overload. Why didn’t you guys fix that”? Well, the answer is you can’t. It’s there on the tape. You can’t go back in time and undo it. That’s what’s there. So that’s part of the joy too, you know?

It seemed like it wasn't even a question that you would stick to an all-analog chain during the mastering process. Can you speak to that? Was there ever any sort of pull towards digital in any way, or was it a non-negotiable for you?

Yeah, non-negotiable. What’s in the groove is literally the waveform. It’s not ones and zeros it is the actual waveform. And when you hear music or you hear speech, the air gets excited by the event. I’m making the air move a certain way and you can hear it. It’s physical.

With the LP playback system, it’s remarkable that it works when you see the complexity in it, but all you’re really doing is you’re amplifying that waveform, whereas, with digital, you are dealing with ones and zeros. And you’re using sophisticated converters that are trying to operate quickly so that the ear can be fooled into hearing a replication of the analog waveform and they’ve gotten really good.

Digital edits can be great, but when there’s an analog master available, we always use it 100% of the time. We have done some releases — a couple of Joe Henderson records, some of the more modern stuff that were all recorded in the digital era — so there is no analog master. And those have come out in the Tone Poet series, but we make it clear that those are the sources we used. We use amazing converters, and we get great results. But if there’s an analog master that’s what we use, 100%. If they can’t find it or it doesn’t exist then I don’t put it out.

Some hardcore fans are a bit critical that the series is putting out stereo records instead of mono, like the originals. How did you decide to go with stereo?

In the realm of Blue Note collectors of original releases, I am one of them. I have tons and tons of original Blue Notes and a lot of people got into collecting the monos, which is great. There’s no right or wrong about it. To me, when we first started doing this back in 2007 at Music Matters we started to hear for the first time the actual master tapes. The goal changed from what we thought when we started: We thought we should try to make them as much like the original record as possible. When we heard the masters, it was shocking how incredible those things were. I thought I knew a record that I’ve heard my whole life, and then I heard “Cool Struttin’” put up the master tape. Our goal changed right then. We wanted to bring people back to what happened that day in the studio. Let’s try to bring them right to the event.

And if you think about when you go to a jazz club, let’s say, and you’re sitting there in the front row, you’re not going to hear the horn players, the bass player, the piano player, the drummer all lined up in the center. They would never do that. They’re spread out on a stage. In the era when Blue Note just started, they didn’t have stereo, so everything Rudy recorded from 1953 up to the beginnings of 1957 was all mono to begin with. When we release those, which we have and will continue to do so, they’re mono because that’s all there is.

Later, Rudy starts recording in stereo and an interesting thing happens that I was unaware of until we started looking at the master tapes. Those master tapes, all say something on the bottom. Each one says, “Mo master”; mo meaning monaural master. “Mo master made 5050 from stereo.” What Rudy did was, the recordings were all in stereo — to get mono. This is a little bit of an overstatement, but if you have a mono button on your preamp, you could do the same thing. There’s a little bit more to it than that, but there was only one master and that master was stereo. He summed the channels to get mono so that he didn’t have to have two machines going at the same time.

You get to the modern era and it really hasn’t changed, you know? It keeps growing and morphing. Blue Note has always been about keeping ears to the ground and presenting, as they say in the logo, “The finest in jazz”.

How does Blue Note fit into the history of jazz? What's Blue Notes’ place in it all?

Well, they started in 1939, and the initial releases were by these Boogie Woogie piano players, Midlux Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons, and some others. The two guys who started the label were both Jewish German immigrants. In fact, they got out of Germany right before the war. They ended up in New York and they had seen some concerts in Berlin as they were growing up and knew they loved the Black American music that they’d seen.

They didn’t have much money, found these boogie woogie players and arranged for a recording session. They recorded these guys, pressed up some records, sold them at a few record shops as best they could and that’s how Blue Note started.

Historically though, Blue Note introduced so many things in the history of modern jazz. Like Thelonious Monk, his first records were for Blue Note. Nobody would touch him because he was considered commercially a non-entity, I mean, musicians loved him and Francis and Alfred liked what they heard. They knew it was important. And even though the records weren’t selling, they kept making records with Thelonious Monk. We’re talking about the late ‘40s at this point. Then the music began to morph. You had bebop like Charlie Parker and all that.

Blue Note was really key to documenting all of that. That’s where that really came from, and then you go all through the ‘50s and ‘60s, and you’ve got Blue Note continuing its hard bop roots, but morphing into the avant garde, and then in the 70s funk starts to be an element in jazz.

It goes to the whole point that jazz isn’t static music. It’s ever-changing, and Blue Note was too. Those two guys had their ears to the ground and knew all the musicians.

You get to the modern era and it really hasn’t changed, you know? It keeps growing and morphing. Blue Note has always been about keeping ears to the ground and presenting, as they say in the logo, “The finest in jazz”.

I think it's really important to underscore the idea of documentation. I feel like that gets lost when people think about vinyl or just recordings in general that it is a documentation of a moment, which is very special. Was that a concept that was thought about when Blue Note started?

Without a doubt. For both Alfred Lion and Francis Wolfe, documenting the music was paramount to them and remains to be incredibly important with the current label.

We’re not dealing in an area where we’re talking about millions and millions of records being sold. This is not the top 10 or anything, so there’s an element of art that’s really important and Blue Note has really always stood for that. We want to sell records and keep going, so there’s an element of ‘Gotta stay in business,’ but the artistic element is really the primary goal.

I read that Charles Lloyd and the Marvels are kicking off this next series starting in March with a brand new record. Can you tell us a bit about that? I’m sure that’s special to you since he gave you the “Tone Poet” nickname.

Charles and I have known each other for many years and we’ve always been working together. I think we started working together in the early ‘90s. He was on ECM at that time and we began to do sessions together. And I noticed my credit on those records would be “Joe Harley, Tone Poet,” and I was doing what normally would be considered production work. I’d be in the studio to help run the sessions and that sort of thing. I still get emails from him almost everyday and they always say something like, “My dear TP.”

And I mean, I’ve never tried to say, “Charles, what do you mean by that,” because we don’t really talk in that way, but I think he knows someone’s really caring about the presentation of sound that is honoring the music. I believe that’s what he means. And Don Was would hear Charles call me that all the time. Don actually suggested using it as the name of the series, and I was okay with it.

I also love that tone has the other meaning of when you're creating an atmosphere or mood as well. At least from my perspective, you do create a very special mood with your work and especially with this series..

Thank you, that’s great to hear. When trying to come up with what to release, I get asked a lot, “Well, how do you pick the titles?” I listen to music all the time and with Blue Note plus its subsidiaries, it’s endless. You keep thinking it’s finite and you’ll get to the bottom or the end but you never do. And I sequence the release in a way that I hope is interesting to people. Is there a formula? Nope. It’s just totally by feel.

It’s unbelievable how much they recorded, and they recorded so much that they lost the tracks of what they had, so things didn’t come out. There were occasions, although not as many as you might think, where a record didn’t come out because the session was substandard in some way. But by and large, it was the case that many artists would ask “Well, why didn’t you put this out?” and the label would say, “We were so busy.” Frequently the artist would respond saying, “Oh, I got something much better now. Check out my new music.” They might have been getting ready to pick up the old one, but they would go along with it so that session would get shelved and lost in the shuffle — essentially forgotten.

It’s really nice to be able to take the time and go through everything. When you listen to them fresh, you find so much stuff that is absolutely as worthy as anything that came out. It just didn’t see the light of day.

Are there some especially notable upcoming releases that you want to kind of talk a little bit more about?

Andrew Hill’s 1969 album Passing Ships. Andrew Hill is another one of these singular artists that you know his music the minute you hear it, in the same way when you hear Monk, you just know. You can listen for five seconds to go, “Okay, that’s Monk.” Andrew Hill’s the same way. He has such a stylistically singular way of dealing with harmony and harmonic structure. The record is made with a larger band that has been a favorite forever, but it was only released originally on CD. This release will be the first time this has ever been on vinyl, so that’s highly exciting to me. It’s all been mixed to analog so it’s analog all the way. That’s coming out very shortly, and that one’s important to me.

There’s a record by two artists that most people will go, “I have no idea who these people are,” but the musicians are Curtis Amy and Dupree Bolton. It’s called Katanga! and I can’t wait for it to come out because I think people are going to be just shocked. I have test pressings and when I play it for people, it’s always the same. They always say, “Wow, who are these guys?!”.

In Dupre Bolton’s case, it’s a sad story. He’s a brilliant trumpet player right there with Lee Morgan or anyone you want to mention. He had his own voice but he spent a lot of time in prison. And so only was afforded a few opportunities to record. This is one of them, and it’s a record that sort of transcends the great musicianship. The tunes are amazing. It’s soulful. I was playing it the other night and thinking that this is one of those perfect records. It puts you in a place that is so deep, and so I’m excited about that.

It’s hard to pick. It’s like you have 100 children, let’s say, which one is your favorite child? We did one the other day and it was important to me. It’s a record from Gerald Wilson, who was LA based and he was a big band arranger composer. So many great players came through his band, and his son is Anthony Wilson. We were mastering a record called Moment of Truth, which is one of Gerald’s greatest records. And even in the era of COVID, we’re all masked up when we’re mastering and I asked Anthony if he wanted to come by because we were doing his dad’s record. He came over and as soon as he came in, the tapes went up and sounded ridiculously amazing. It ended up being very emotional. When you’re hearing those masters on a great set-up like at our mastering studio, it’s like his dad’s alive and you’re hearing it like they’re there.

There’s also a Grant Green record that’s called Feelin’ The Spirit, which is a record that a lot of people think may be one of the greatest things he’s ever done. It’s all gospel music and it’s just amazing. Herbie Hancock’s on that record and he just — it’s some of the best supporting work I’ve ever heard, just amazing.

You can follow Harley on Instagram at @jazzsarawati for all of the behind the scenes footage of his work.

Blue Note has announced the entire 2021-22 schedule for the Tone Poet Series, and will start with Charles Harley’s new record “Tone Poem”, on March 12th.

Blue Note’s 2021-2022 Schedule: http://www.bluenote.com/2021-2022-tone-poet-vinyl-series-line-up/