In conversation with Small Medium Large, a new quintet from the burgeoning new West Coast jazz & improvised music scene. In 2018, LA-based jazz and post-rock guitarist Jeff […]

Last Wisps of the Old Ways: In Conversation with Derek Piotr

Step into a world of North Carolina mountain singing with music archivist Derek Piotr.

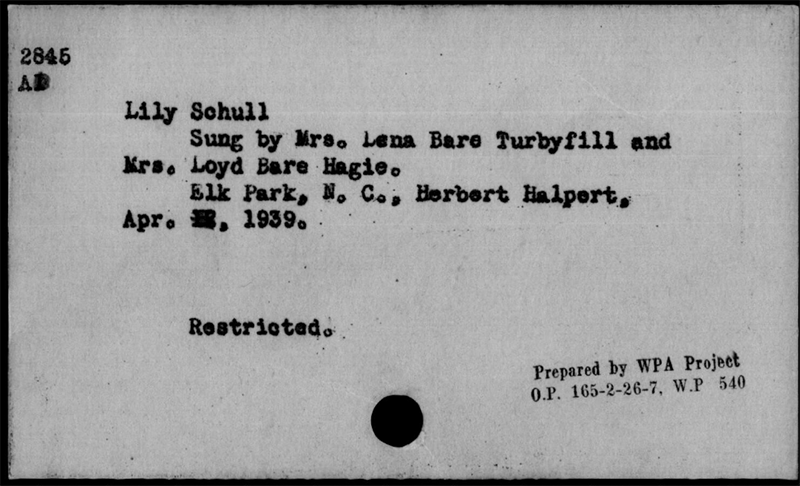

A series of recordings collected by Herbert Halpert for the Library of Congress in 1939 served as the launchpad for two new compilations showcasing the vocal talents of North Carolina mountain singers, specifically Lena Bare Turbyfill.

Blake Wagner talks to archivist and musician Derek Piotr, who was responsible for curating these songs last year on reissue label Death Is Not The End. The compilations are titled Last Wisps of the Old Ways and Ever Since We’ve Known It.

Is it kind of freeing, working on a project that isn't wholly yours? The voices on these two compilations are a mix of vintage archival as well as personal recordings. How did it feel to just let the tape run?

It’s so much easier to be enthusiastic about someone that isn’t you. I used to play shows all the time, like three times a month or more. You’d get off stage and there’d be ten people wanting to talk to you all at once. But it’s so thankless to put a record out and then not tour it.

So, in a way, these compilations have been way easier for me to talk about. In the beginning when I was thinking about Lena Bare Turbyfill, trying to bring her back from the brink of obscurity, I kept checking in with myself, and I was like, “Am I sick? Am I just fixated on this woman because she’s the first thing I heard? Is this just like a weird bias that I have?”

Then, after I listened to all of these tapes from the Library of Congress, I realized, no, she’s by far the best of the seven people recorded in 1939. You had her two sisters, her father, her sister-in-law, and then Ben Duggar, who I think was the mayor of Elk Park, North Carolina at one time. There were myriad other people in the room, and some of them even sang the same songs. Lena’s sister, Lloyd, sings a version of “George Collins” as well, and it’s just clear from an aesthetic and musicianship and athletic level that Lena was the best singer. She had the best control. She had the nicest briskness. She had the sweetest tone in her voice.

I think the family agrees that Lena was the best in terms of technical ability. But I had some moments of self reflection while completing this, and I was like, “Okay, I’m gonna be talking about Lena Turbyfill again.” I don’t want to be too one-note.

There are other field work projects that I am interested in. There’s a woman who was born in 1844, who lived in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, and she’s kind of the next person that I’m fascinated by. But these things take time. So while it’s much easier to talk about this compilation, I’m already thinking beyond it.

That being said, Lena is the best singer I’ve heard in a really long time, so the simple fact that her face has appeared on places like WFMU and NTS means she has a shot now. I want to at least give her a chance, and I think it’s been going really well. I have this theory that this was sort of her destiny – someone would have done it if it weren’t me.

I love the title of the first compilation, Last Wisps of the Old Ways – capturing something before it disappears into the ether, like the legacy of Miss Lena.

I'm curious about the title of the second compilation, Ever Since We've Known It. Why did you choose to call it that?

There’s a compilation Lena was featured on, put out by New World Records, titled Oh, My Little Darling: Folk Song Types. On that compilation, Lena and Lloyd sing a song called “Lily Schull,” which they sing together in unison; they’d learned it from their sister, Sabra, who is recorded singing that ballad on Last Wisps. They sing it together and Dr. Halpert asks – because it’s a gruesome song about murdering and burning a body and then getting hanged for it – if they always sing it together when they happen to sing that song, and Lena replies, “Ever since we’ve known it.”

So I think it has a double meaning, right? It’s like, “Ever since we’ve known it, we’ve sung it that way.” But it could also be taken to mean, “Ever since, we’ve known it.” Like, “Ever since I’ve seen or heard, I’ve just had this knowing.”

That lack of formality is very present in these recordings. They’re not manicured in the way that a lot of modern reissues are. People are attracted to authenticity, but when they're confronted with something kind of messy, it shatters their sense of disbelief because it doesn’t really cater to the modern ear.

There are so many recordings of ballads that are peaceful and fine to the ear, but this doesn’t need to be one of them. That’s already happening. I’m friends with Sheila Kay Adams, and I love her very much. On some of her recent recordings, you can tell that she’s in a recording studio, they’ve got reverb on her to some degree to make it sound beautiful, and it does sound beautiful – a lot of ballad singers do that, because it can be very awkward. Like when you’re riding a train and the power shuts off, and the blower stops, it’s that feeling of realizing, “Oh, there’s no reverb.”

My point is, we don’t all need to be peaceable to the ear to have beauty, and part of the magic of some of this stuff is that it is so brief and it is so mixed into the clutter, like the “Cumberland Gap” at the end of Last Wisps. You hear Lena and Lloyd’s voices for like, two seconds, and that’s my favorite thing on the compilation because it just hits you out of nowhere and then it’s gone.

How did you wind up in North Carolina in the homes of these people, recording their music?

With Lena’s family, I’d found the recordings and they were aware that the songs had been recorded. But they were very enthusiastic about remembering her. That snowballed into wanting to go meet them. And when I read the words, “Elk Park,” it really activated something for me in a weird way. Being in Elk Park several times as I have now, it’s one of my favorite places on earth. It’s this beautiful small town full of lilies and streams. I’m hoping to move to North Carolina in a few months because I can’t get it out of my head.

That went very well for me, and everyone that I’ve met, they’ve just been magical and welcoming and loving. They consider me family now. So it’s been really unusually warm. I’ve been talking to someone who is the granddaughter of this gentleman who was recorded in the early ‘30s on wax cylinder. She seems really sweet, but I think also, this late in the game, if people know that their ancestors were recorded, they’re excited by the fact that someone’s found these recordings and wants to celebrate them. I think that gets you over any amount of trepidation that would be present.

It’s funny to me to be doing this work and have people say, “No one does this kind of thing with folk music. what you’re doing is pretty new and unusual,” because it’s folk music, it’s always been around – by nomenclature, it feels like tradition. A lot of people think that this kind of field recording can’t be done anymore because there aren’t enough people that remember, and I kind of want to fly in the face of that.

I guess what I’m fixated on are these literal last wisps of someone remembering someone who they can recall through an oral tradition.

The word “folk” by default implies some sort of tradition, which means, “Okay, does this have to be some elderly woman who was born 150 years ago for it to be a legitimate recording of a legitimate song?” There are plenty of young people who are making and singing and playing very authentic renditions of folk music in a lot of these places.

Ultimately the goal is to give someone something that is so beautiful that they might want to interpret it, you know, show someone a recording made years ago that they would want to keep alive today, not just the recordings themselves, but what people can do with it.

That being said, what I’m interested in are these old ladies with this memory of their fathers singing – whether he was, you know, mowing the yard, or working, or whatever he was doing – and he would always sing that one song. For instance, this woman that I’ve been speaking to whose grandfather was on the cylinder recording – his name was Adam Morris, her name is Lorna Morris Cyr (you can look her up online, she does these amazing psychedelic paintings with aliens and stuff in them) – she’s 78. She can remember Adam bouncing her on his knee when she was a child and he would sing to her. She still sings to her grandkids. She’s not a musician but there are people all over America who had grandfathers that sang, and they can still recall those songs.

I guess what I’m fixated on are these literal last wisps of someone remembering someone who they can recall through an oral tradition. In England, I spent an afternoon on a small farm in West Yorkshire with Will Noble, a well-known English folk singer. He used to go to hunting clubs, and that’s where all the men would gather and they’d sing things like “Derwentwater’s Farewell” – these long, beautiful, 11-stanza things with tricky harmonies on top. I asked, “Do you remember anything from before the hunting clubs? Before you decided to become a singer?” And he had two verses, mostly, “La-la-la-la… (muttering) and it’s all for the pricketty bush…,” and I said, “Oh, that’s the child ballad ‘Hangman!’” It meant more to me than the complicated poems and tricky harmonies, because he just remembered that through oral tradition. He said, “When I was two or three, my uncle sat me on the tractor and sang that while he was plowing the fields.” That was so interesting and cool. He certainly learned authentic songs when he was in hunting clubs, by gentlemen that probably got them sung to them by their fathers. But the fact that he could remember his uncle singing, that was the golden nugget of the day.

These two compilations do have a certain lived-in quality. It doesn't feel like Lena’s singing for a microphone. It sounds like she's singing for herself, like you could be working or sitting, enjoying an afternoon alongside her, just listening.

I think Lena was a very relaxed singer. When Dr. Halpert visited, they may not have owned a radio yet – it was 1939. Most families down there probably didn’t have a radio. I know a woman from Tennessee who said that she didn’t own her first electrical appliance until the 1970s. A heater, maybe? Their father would warm a quilt on the fire.

What I’m getting at here is part of the reason Lena sang the way she did is because she’d never heard anyone sing any way differently. She hadn’t heard Bing Crosby. I would be very surprised if she’d heard pretty much anything that was a performance, aside from going to a county fair. There’s only one mention of electricity in any of the songs she sang, which is in this song called “Jim Blake”: “‘Your wife is dying,’ came over the wires today.” All the other songs are so old that they predate electricity, and they’re about sailors and lords and farmers. So I think that she was very much existing in this space where there was nothing but your voice to pass the time and there were no performances. There’s your radio right there.

We could open a bottle of wine and talk for hours about how detrimental radio and modern media has been to voices like Lena’s. You eventually had the crooners and the Elvises, who could get really close to the mic and sing softly. Not only did it change the way people emulated singing, but it changed the subconscious association people made with singing. Everyone just stopped singing as forcefully, because they didn’t have to.

It's a complicated blessing for us that she could have one foot in both realities.

It was kind of a perfect storm. I heard an interview with Herbert Halpert that echoed this sentiment. He was explaining that these men down South in black felt hats with guitars were dying to have him record. They knew that he was coming and they just wanted to impress him and be in front of the microphone for the first time ever. He would obviously quiz his informants before he set about recording them, and if they said they knew things that seemed more modern, he simply wouldn’t take them. He wanted to capture these musical memories rather than whatever was on the radio last week. He was sort of chasing time – the same thing I’m chasing almost 100 years later.

For further listening, we highly recommend checking out Death Is Not The End on NTS radio.