A communal deep listening session happens Friday, January 30th at Agora Records’ back warehouse space. Sound by Mobius Acoustics. Ever quotable, Richard D. James has always been his […]

In Conversation: Mitsuto Suzuki (Electric Satie)

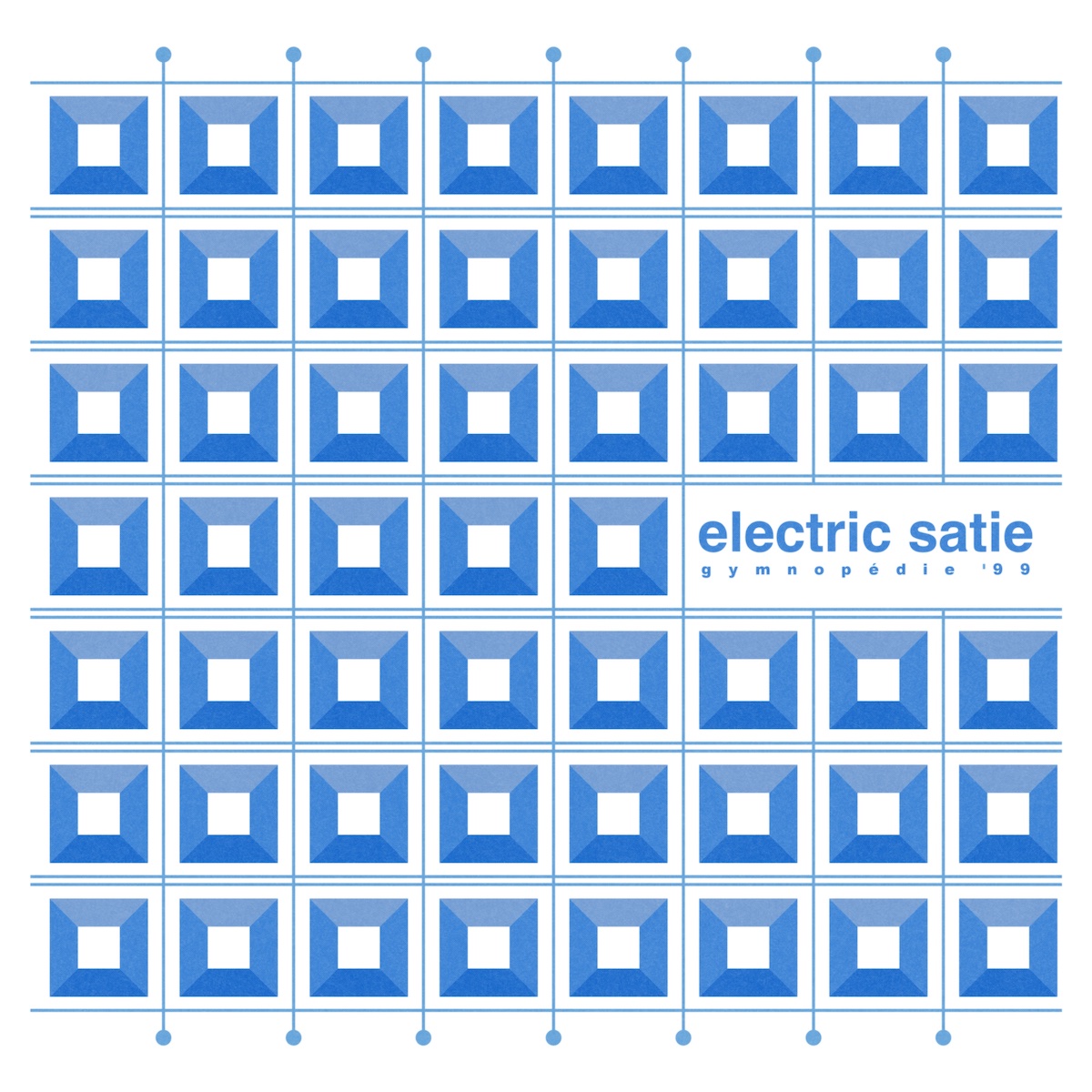

Originally released on CD-only, Electric Satie – Gymnopédie ’99 will be available on vinyl this Friday via In Sheep’s Clothing Hi-Fi Selects.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, a generation of Japanese artists who grew up on the pioneering electronic sounds of Yellow Magic Orchestra began experimenting with the latest consumer musical technologies of the time from manufacturers like Roland, Korg, Yamaha, AKAI, Nord, and others. Concurrently, the rising sound of techno from Detroit and the United Kingdom via labels like Warp and R&S spread like wildfire through the country’s clubs and record stores.

Part of this generation, Mitsuto Suzuki is a Japanese composer largely known today for his work on video game soundtracks. His earliest releases include 1994’s Voices Of Planet, an acid techno set under his ARP-2600 moniker, “Line Age” under Man Machine (a Kraftwerk reference?), and “Medium Feedback,” which was included on Haruomi Hosono’s 1996 Daisy World Tour compilation album.

In 1998, Suzuki released a curious one-off conceptual album titled Electric Satie – Gymnopédie ’99, which reimagined the beloved minimalist piano compositions of Erik Satie with electro-rhythms, synthesizers, and digital effects processing. Wildly imaginative and varied in style, the album explores downtempo bossa nova, freestyle ambience, and chillout room IDM, not far from the music featured on Music from Memory’s Virtual Dreams II or Warp Record’s Artificial Intelligence. Originally released on CD-only, the album will be available for the first time on vinyl this Friday via In Sheep’s Clothing Hi-Fi Selects. Pre-Order available now: https://insheepsclothinghifi.com/product/electric-satie-gymnopedie-99-lp/

Below, In Sheep’s Clothing’s Phil Cho spoke with Suzuki to learn more about his musical background, working as a video game composer, Yellow Magic Orchestra, Japan’s techno scene in the ’90s, the creation of Electric Satie, and more!

What is your musical background (training / education / early musical experiences)?

I grew up in an environment where music played very naturally. The Beatles, Elvis Presley, analog records and cassette tapes of Japanese music, and the now precious reel-to-reel tapes were all around me by the time I could remember. I learned to play keyboard instruments, but my mind was taken by video games before I could enjoy them.

I read in your bio that you have synaesthesia? How has this affected your experience with listening to music and also influenced your composing?

It is difficult to define synesthesia, but I think I have naturally acquired the sense of perceiving sounds in terms of colors. I also perceive sound through sight. For example, I hear sounds in my head that are different from real sounds, such as fireworks weeping, which is a summer tradition. In my opinion, I think it is something that was acquired later in life, arising from the music I listened to repeatedly in my childhood, or closely intertwined with visual or other impressions. Although I like violets, deep blue, and ivory tones, I don’t always use them to create music, so I can say that they don’t have a great influence on my compositions.

Listening to your music, it’s clear you have a deep love for synthesizers / synthesis. You even had a project called ARP-2600. What were your first experiences with synthesizers and electronic music composition?

That is a very nice thing to hear, and something I value very much in my music making. One of the fascinating things about synthesizers is that you can create your own tones that do not exist in nature. I was fascinated by the connection between synthesizers and music, and that is why I am here today. I first started playing with a synthesizer that belonged to my older brother, and it wasn’t until the first year of junior high school that I was able to compose a piece of music. I composed music using the Family Basic, a peripheral device that could expand and program the Family Computer at the time. The Family Basic had three simultaneous sounds, so I was able to compose music in a playback environment that was almost identical to that of the home video game consoles of the time. Looking back, the feeling I had at that time may have been the first step leading to my current career.

It is said that you were inspired early on by Yellow Magic Orchestra. Can you share some of your favorite Yellow Magic Orchestra tracks?

It seems that as I get older, my tastes repeatedly change, but right now I’m on about my third round of listening to “Solid State Survivor” a lot. I sometimes talk about this kind of thing with my music friends and it makes me very happy. It is also YMO that made me cry spontaneously when I listen to music. Mmm, yes, it is a very difficult question and precious at the same time.

Where did the inspiration and concept behind Electric Satie come from?

I remember that it was one of the projects of the music production company I belonged to at that time. Various concept albums were being produced at that time, and I have heard that the catchy name “Electric Satie” and the concept of “covering Satie with electronic instruments,” were thought up by Yosuke Kakegawa, who is still one of my music friends today.

I’d love to know more about your life during this time. Were you visiting dance clubs? What artists and types of music were you listening to?

I worked at a game production company during the day and went out on weekend nights for fun. During the 10 years around that time, I probably went to the dance clubs the most, and I was in and out of my music friends’ parties and label parties quite frequently. I was greedy for only the sounds I liked regardless of the size of the venue. Derrick May, Claude Young, DJ TOBY, Underworld, Hard Floor, Susumu Yokota, and countless others. It was right around the time that festivals were starting up in Japan, so I participated in many large festivals. It was a time when I liked to listen to functional music, that is, how simple the music made you dance, but at the same time I liked Squarepusher’s music that combined jazz, fusion, and drum’n’bass. It was very exciting to follow the birth of new music, and it was a time when I was greatly influenced by them.

To me, your work feels connected to the music scenes featured in a recent compilation titled Virtual Dreams II: Ambient Explorations In The House & Techno Age, Japan 1993-1999 and also artists like Yoshinori Sunahara or Rei Harakami. Did you have any connection with these artists / did you feel part of a specific music scene during that time?

There were business contacts such as remixes. It was a time when I experienced firsthand the establishment of Japan’s techno scene with SYZYGY in Fukuoka, FROGMAN and TRANSONIC in Tokyo, and TOREMA in Osaka, but I did not feel that I was a part of the music scene. Because I felt the potential of electronic music, which could be called a universal language, and every day I was writing songs and sending out demo tapes, I was busy expressing myself. At the same time, it was a very happy time and routine work.

This album was produced in collaboration with AO Productions (Ryoji Oba). What was the process like working together and collaborating on this album?

While making and digging cutting-edge techno and electronic music at the same time, I encountered the music of Subsurfing, released on R&S Records’ ambient label, Apollo. The soundscape and worldview is overwhelming, I was greatly shocked by the uniqueness of their sound, which seemed to ignore the techno scene in a good sense, especially the beauty of 808 kick and sine wave, and the dub mix. At first, I thought they were British or German artists, but as I researched, I found out that the main member of the band was a Japanese, Ryoji Oba, and I immediately sent a demo tape to him and he agreed to take me on. Anyway, I think my energy and speed during this period were so fast that it was scary, but it is also true that it has led me to where I am today. As for the collaboration for the album, I think it was a single word from Mr. Oba: “Mitsuto, it’s been confirmed, so let’s do it!” The day after I submitted my resignation to the game company I was working for at the time, I holed myself up in the studio and started working on the album. Looking back, this was one of the turning points in my life.

What instruments / synthesizers / technology was used in the recording of Electric Satie?

I used a Prophet 5, Memorymoog, PPG Wave, Juno 106, JX-8P, nord modular & nordlead, AKAI & Emu samplers as my main instruments, making it truly “electric”. I mainly used a Mac, but I think I also used a Yamaha QX3, a hard sequencer, which I had been using for many years at that time. I also feel that the production environment was one in which hard disk recording and tape media coexisted, which is also a sign of the times.

“Electric Satie wasn’t club music, it wasn’t pop music or easy listening. I remember it as a very difficult piece to interpret. It was electronic music based on the works of Erik Satie, nothing more, nothing less.”

I love track 1 “Gymnopédie # 1 - Universe,” which has a sort of bossa-nova feel to it. How did this composition come together with features from Brazilian vocalist Silvio Anastacio and percussionist Marco Bosco?

At that time, Silvio was singing at a Mexican restaurant that Mr. Oba used to take me to. Mr. Oba said, “Hey, Mitsuto, I think that guy should be the vocalist for Satie’s album”. At first I thought he was joking, but he was really serious, and before I knew it, Silvio had been chosen. While Mr. Oba creates multifaceted music like Subsurfing, he is an academically educated artist with a good understanding of pop music, so the bossa nova approach came naturally to him. I was in charge of synth manipulation and programming of drums and sequences, and I am proud to say that even now, it is a very strange track that I have never heard before. I don’t remember Mr. Oba telling me in detail about musical matters, but he was like a mentor to me, showing me how to behave and act as an artist through the production. I was impressed that Bosco brought a lot of friends and a lot of percussion instruments to the recording session. It was so cool that I wondered what kind of pirate came over here!

“Gymnopédie # 2” features an interesting mix of soprano saxophone from Hiroyasu Yaguchi along with percussion sounds. The saxophone gives it a jazz feeling, while the percussion is almost new age. What kind of world were you trying to build with this track, and also the overall atmosphere of the album?

I never thought of making it new age when I was working on it, but now that I hear it, it sure sounds like it, lol. I grew up listening to Mr. Yaguchi’s saxophone, so it was like a dream come true to be able to work with him. I think the recording itself was done in a few takes and finished quickly. The percussion was created by using a software called Recyle, which had just been released at that time, to break down looped material into separate parts and digitally shift the grid before inputting them. The recording and mixing engineer was done by Shinichi Akagawa, who is considered a master in Japan. Mr. Akagawa passed away in 2018, but he fully supported me when I was still young and not used to studio recording. The many works we have made together since then, including “Electric Satie,” are irreplaceable and will live on.

“‘Freestyle Ambience’ is a coined word that incorporates my love of hip-hop culture and improvisation, as well as the idea and atmosphere of not belonging anywhere.”

I also really love the spoken word ambient track “La Lune.” Where is this vocal sample from and can you share any more information about the creation of this track?

The bass track was created by jamming with Max patches at a friend’s house, recorded on DAT and then edited. The sound source was a Roland JD990, then I overdubbed PAD and rhythm track in real time in the studio. The vocals were recorded by a French narrator and edited. The sound effects in the middle and at the end of the song were recorded in the field on a pedestrian bridge in Shibuya late at night in 1998.

“Freestyle ambience” is mentioned on one of the tracks, and seems to be a descriptor you use for your sound. Can you talk about what that term means?

It is a coined word that incorporates my love of hip-hop culture and improvisation, as well as the idea and atmosphere of not belonging anywhere.

“Vexations” includes a spoken passage created using a text-to-speech generator. It is quite an experimental track and sounds a bit like musique-concrete. Where is this text from?

This track was primarily created under the lead of Takashi Watanabe, who participated in the project as engineer/artist. I think the strange sound effects and synthesizers were created using SuperCollider. We worked together one night just before the deadline, and when we realized, it was completed. You could say it is a different song on the album, but the original “Vexations” itself is difficult to understand, so I figured it wouldn’t be a problem. I like the track very much as a result.

The album was released on Roux, a sub-label of Victor, in 1998. What was the critical response when it was originally released?

“Electric Satie” wasn’t club music, it wasn’t pop music or easy listening. I remember it as a very difficult piece to interpret. It was electronic music based on the works of Erik Satie, nothing more, nothing less. I would be lying if I said I was not anxious, but the moment I heard “Gymnopédie # 1 – Universe” on the radio, I understood that my doubts were too trivial. I spend a lot of time dealing with the process of completing music, not just “Electric Satie. After completion, the power of the music itself becomes like a child that becomes independent. After some time has passed, I cherish the objective viewpoint and feeling of “Who made this music, it’s cool,” and if the music is remembered as a source of comfort and enjoyment for those who listen to it, I will be very happy. That was my thinking when I created “Electric Satie” and it is the same now.

You’ve been composing music for video games now for many years. How has your video game soundtrack work influenced or affected your solo production?

The concept of video game music is different because it is an element of a production method that enhances the game. Of course, they are the same in the sense of “music,” but the difference lies in whether there is a theme or not, and the final judgement is very different. However, both video game music and pop music have a common method, and that is often useful. Both are essential elements for me, and I can say that they are in perfect balance.

Finally, what are you working on today and are there any of your other projects from over the decades that you’d like to share and highlight?

Currently, our main activity is the electronic shoegaze unit “mojera”. We are a unit that mainly thinks about spinning out the sounds we like flexibly with people we want to make music with. And “Electric Satie” is the first time I’ve listened to it in a while on the occasion of this vinyl release, and I enjoyed it with a very fresh feeling. We are just beginning to think about what it would be like to perform live with the current feeling, so we may be able to unveil it in the near future. I will go anywhere as long as there are people who are willing to listen to it.