Piano-cello duo Salenta + Topu share five favorites ahead of their live performance this Friday at In Sheep’s Clothing HQ. “Two old souls creating music not of this […]

Revisiting ‘Ingmar Bergman: An Unrequited Love of Music’ (2011)

Charlotte Renaud’s incredible essay on the celebrated Swedish auteur’s devotion to classical music.

‘If I was forced to choose between losing my hearing or losing my sight, I would keep my hearing. I can think of nothing worse than having music taken away from me.’ – Ingmar Bergman.

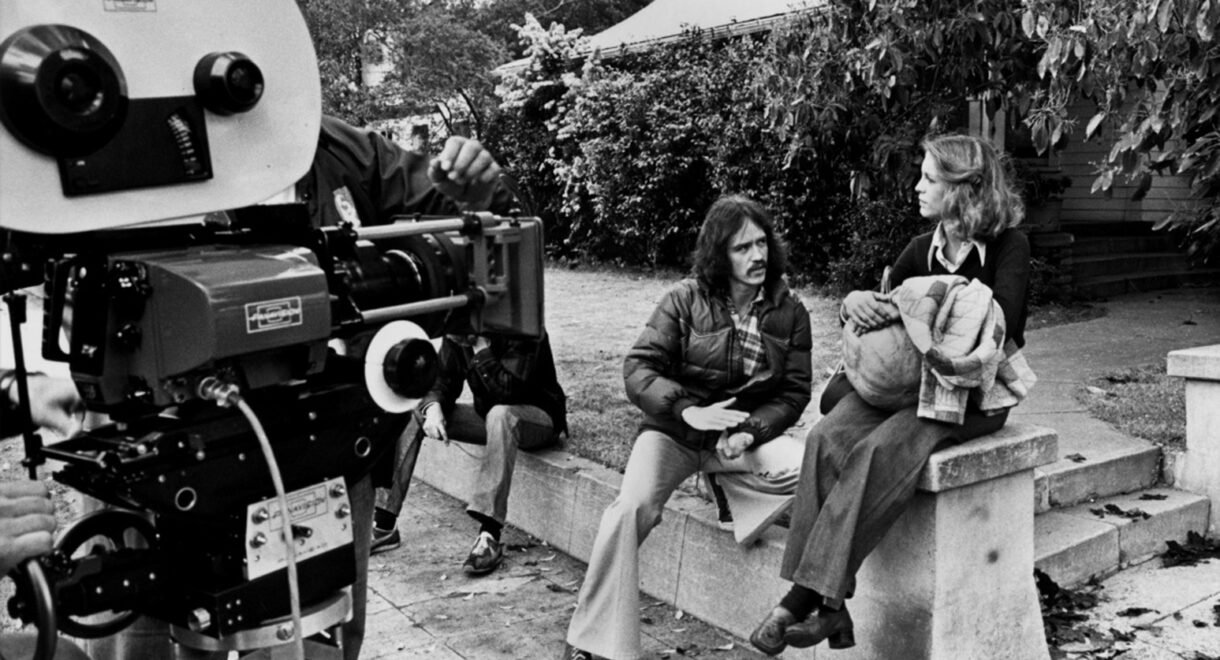

Ingmar Bergman was a visionary Swedish filmmaker responsible for creating some of the 20th century’s greatest films. Imaginative and evocative, they reveled in striking and unforgettable images — such as a medieval knight playing chess with Death on a seashore. Before his death in 2007, the master director crafted existential, soul-searching works that resulted in one of the most moving bodies of work in cinematic history.

Bergman made more than 50 films in his long career, including The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, The Silence, Cries and Whispers, Persona, Scenes from a Marriage and Fanny and Alexander.

But there are many sides to this so-called ‘gloomy Swede.’ He wasn’t just captivated by cinema’s imagery, but as the quote above confirms, Bergman was also deeply devoted to sound.

Charlotte Renaud, on Bergman’s website, has written an illuminating essay that breaks down Bergman’s relationship with music. Of the quote excerpted above, she writes:

“This confession by Ingmar Bergman is rather surprising, coming from a filmmaker renowned for the astonishing beauty of his imagery. His 1975 version of Mozart’s Magic Flute is, however, one of the most wonderful examples of this passion for music. Other examples come through in his various opera productions, including Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, staged at the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm in 1961, and Börtz’s The Bacchae, 30 years later. Nevertheless, the silver screen is where we truly witness Bergman’s impassioned devotion to music, with its central placement in his films and the way in which he borrows countless elements from the classical repertoire.”

Renaud’s goal for the essay, she summarizes, is an attempt “to comprehend the indispensable role music played throughout his career – from Crisis to Saraband. Throughout this study, it becomes clear that Bergman was not only a music-loving filmmaker, but also a true master of sound. For him, the art form closest to cinema was neither drama nor literature, but music.”

What follows are some observations from Renaud’s piece that reveal the ways in which Bergman’s classical repertoire inspired some of his greatest movies.

Renaud writes that Bergman was once questioned about his relationship with music in an interview in 1982. In it, Bergman said, “Music has always been one of the most important sources of inspiration for me, perhaps even the most important.”

Entire films have been drawn from his classical record collection, he noted. Winter Light (1968), according to Bergman, was inspired by his discovery of Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which gave him the idea to stage a film in an isolated church in the Swedish Countryside.

Music also birthed his 1963 film The Silence, which Bergman recalled conceiving after hearing Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. “My original idea was to make a film that followed musical rules, instead of dramaturgical ones, a film that functioned through association – rhythmically, with themes and counter-themes. As I was putting it together, I thought much more in musical terms than I had done before. All that remains from Bartók is the very beginning. The film follows Bartók’s music rather closely, with the dull continuous tone, then the sudden explosion.”

Hour of the Wolf was based on Bach’s The Art of the Fugue. As with Bach’s composition, Bergman’s film stops in the middle of a sentence and remains unfinished.

Here is a great clip of the legendary Glenn Gould emphatically breaking down Bach’s musical architecture accompanied by an excerpt from the famed Fugue.

How did music inspire Bergman? “I don’t know exactly, but sometimes a piece of music creates an emotional link, a situation,” he said. “Music frees up something that wants to be expressed and told.” An emotional discharge sets the imaginary into motion. The Estonian-Swedish pianist Käbi Laretei once explained, for example, how Chopin’s Mazurka in A Minor gave birth to the final scene in Cries and Whispers (where the Mazurka is featured). The title of the film can be linked to an expression used by the critic Yngve Flyckt, when speaking of the final movement in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 14 in E-Major.

‘If I had been given that gift and hadn’t become what I am, I would most probably have become a conductor,’ wrote Bergman in The Fifth Act. Indeed, the filmmaker considered his work similar to that of an orchestra conductor, and he continuously resorted to musical metaphors. He enjoyed comparing scripts to musical compositions. In the preface to Persona, he stated, “I didn’t write a film script in the usual sense of the word. What I wrote seems to me to be more like a music score that I will conduct during the filming.”

We love this essay and hope you’ll read it in full:

https://www.ingmarbergman.se/en/universe/unrequited-love-music