Voices from around the world read Banabila’s words over quietly shifting electronics on Through Global Frequency, released by Glasgow’s 12th Isle. Michel Banabila’s shockingly beautiful Through Global Frequency […]

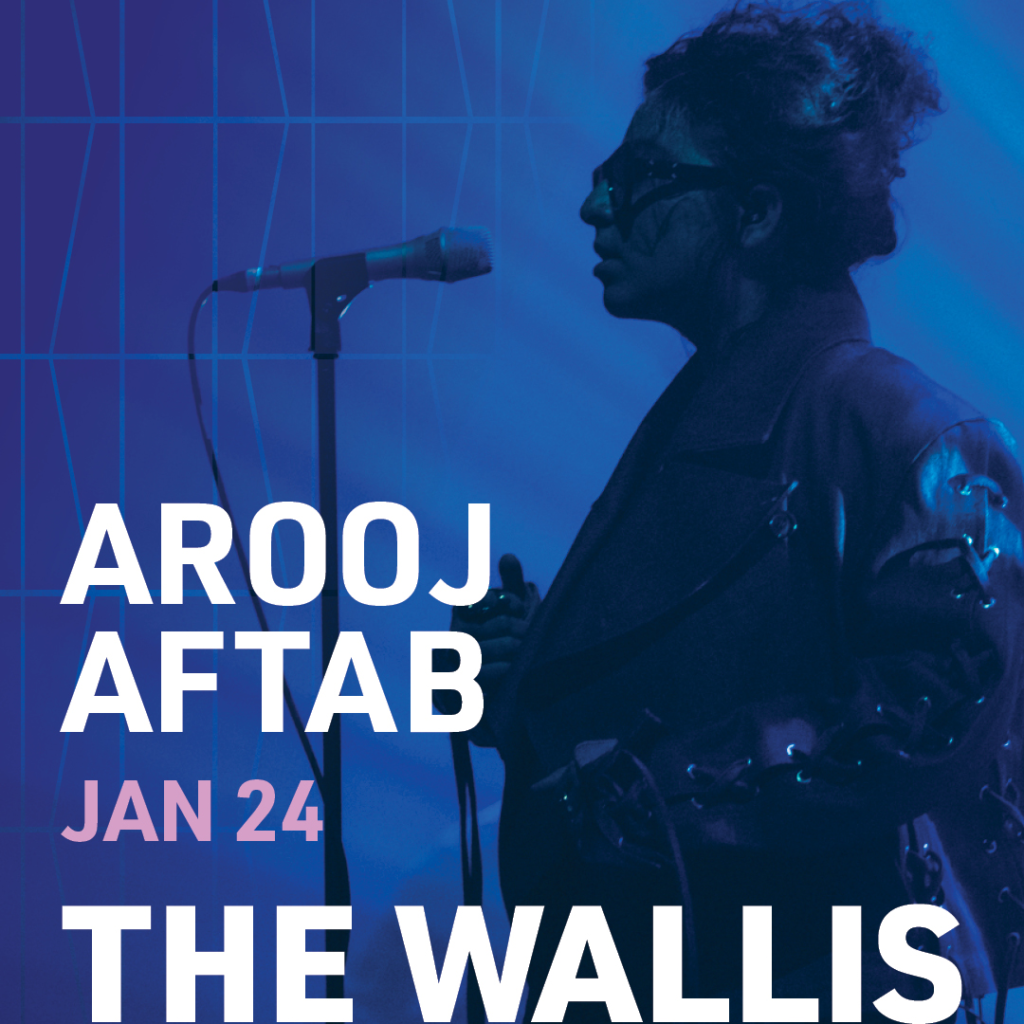

In Conversation: Inside Arooj Aftab’s Listening World

A conversation about her listening habits and life with music ahead of the January 24th performance at the Wallis in Beverly Hills.

Arooj Aftab is a Pakistani American singer, composer and producer whose work moves between South Asian classical music, jazz, minimalism, and experimental pop, creating songs that feel both ancient and eerily contemporary. After growing up between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, she studied at Berklee before settling in Brooklyn, where she became part of a loose scene that includes collaborators like Vijay Iyer, Kaki King and Moor Mother. Her 2021 album Vulture Prince, built around spare arrangements and Urdu poetry, brought her international recognition and a Grammy.

Her most recent album, Night Reign, leans into atmosphere and collaboration, keeping her voice at the center while widening the music around it. The record drifts between jazz, folk and classical textures with a late-night looseness that feels more curious than calculated.

Aftab is an expert at minutiae. In “Aey Nehin,” she quietly shifts the song into double time halfway through, changing the emotional temperature without ever breaking the spell. A fearless singer, she directs the tempo not through percussion but by tethering it to her voice. On “Saaqi,” her collaboration with Vijay Iyer, rhythm bends to her phrasing rather than the other way around.

The artist spent much of 2025 on the road, carrying her music across North America, Europe and Asia with appearances that ranged from intimate clubs to major concert halls, including multiple nights in New York, festival dates overseas and orchestral performances in the Netherlands. The scale of that touring mirrored the way her audience has grown, from a cult following into something broader and more global.

Recently, Aftab hopped on a Zoom call to talk about her listening habits and her earliest experiences with recorded music, a conversation shaped by the reality of life on the road. Constant travel, she said, means long stretches with headphones on, turning planes, trains and hotel rooms into private listening spaces where new sounds, old favorites and half-formed ideas for future songs all start to blur together.

That listening-first approach will come to life when Aftab plays at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills on January 24, 2026. In Sheep’s Clothing will be there as well, setting up a full system and spinning records, shaping the room into the kind of space her music was always meant to inhabit. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

In Sheep’s Clothing: When you think back on your earliest experiences listening to music, what comes to mind, the music itself or the conditions around it?

Arooj Aftab: I would say both things. I think I have some really early experiences of listening to music, like being seven years old. And then I also have experiences listening to music very deeply, when I was first learning to play the guitar. I would put my ear on the body of the guitar and just play one string and really let it ring and then die out, and then pluck it again and let it ring. I would keep my ear against the body of the guitar and just listen to it, really listen to it. I found it so incredible, and I was addicted to it, listening that deeply to isolated notes coming through the body of an acoustic guitar. I also remember doing that in the afternoons on weekends when I was not in school, sunlight streaming through and just a warmth all around — a kind of solitude, a practice of deep listening.

Were there early sounds or voices that taught you patience, music that didn’t resolve quickly but stayed open long enough to reward sustained listening?

I think the whole practice of listening to very lyrical singer-songwriter records from beginning to end, which is something that we used to do and some of us still do. Not even just singers, just listening to records from top to bottom and imagining a cohesive bigger story and the artist’s message and what they were maybe going through. I was very imaginative and I made up a lot of worlds outside the real one. I loved doing that with different records, whether they were instrumental or not. It felt like a zoom-out and an instinct of trying to find the longer idea and the patience instead of just wanting to like the song you like the most and hitting repeat.

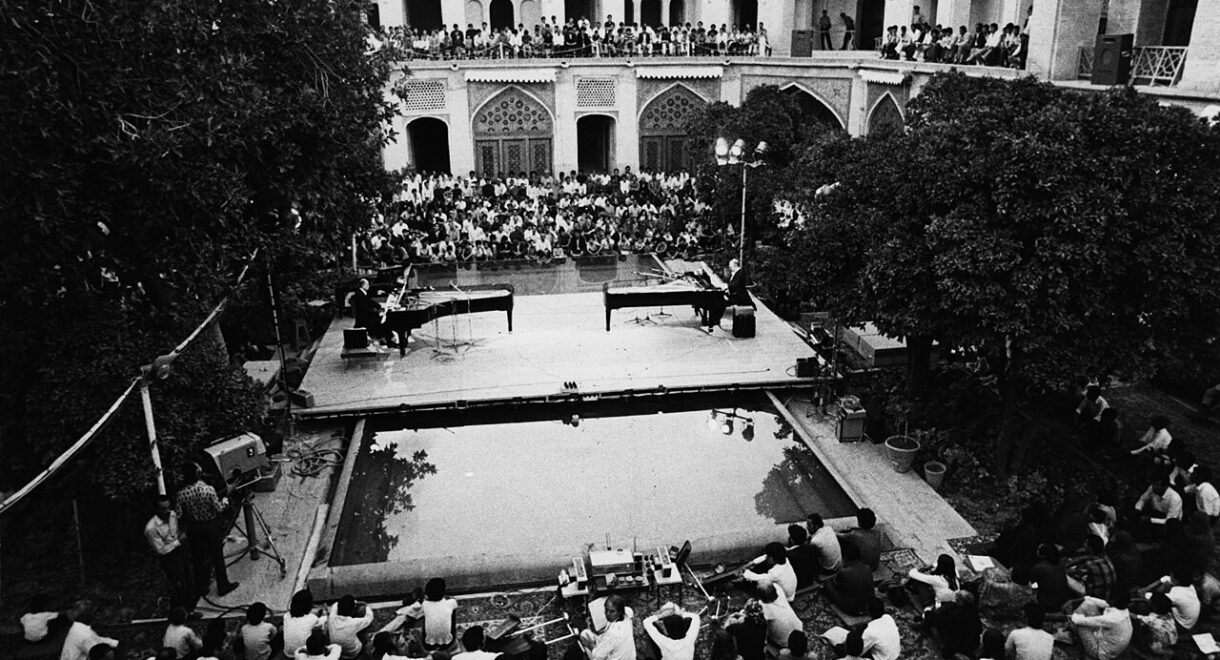

I also remember my parents taking me to some of those evening classical music performances in this beautiful amphitheater in Lahore. You would get there at 7 p.m. and you would leave at 4 a.m. and the performance would still be going. They brought me because I had the patience to sit through it. You take a nap, you wake up, you’re still there. It’s beautiful. Everyone is really taken by it. A really long, precious and patient performance.

“Moving around definitely made me feel free in terms of my ability to write and listen to music. I grew up in Saudi Arabia and that environment was very stark. Listening was very isolated except for my parents’ parties.”

Did your family have a stereo system, like speakers and components, or was it mostly radio?

They had a whole setup because they loved hosting and performing and inviting people to perform at our house. They were music fanatics. We always had a system by which to play music, very organized and very central to the house.

How did movement and migration affect your listening, growing up in Saudi Arabia, then Pakistan, then Boston and New York?

Moving around definitely made me feel free in terms of my ability to write and listen to music. I grew up in Saudi Arabia feeling very singular. But I was young and that was around the time Thriller came out and we would watch all the coolest music videos on MTV. I loved Michael, Janet, Mariah and Madonna. There was also all the incredible music my parents would play at their parties. Moving to Pakistan as a teenager felt like suddenly there was so much community and so much more music. Everybody loves to dance and everybody loves poetry and they all kind of do it together. You are swapping cassettes with friends and surrounded by people who are, all of you, listening to a music that feels inherently yours.

Then going to Boston and freezing our asses off and studying music and learning about jazz and being in another community was really incredible. My roommate was James Taylor’s niece. Suddenly I felt at the center of everything. A lot of confidence was built there and a lot of expansion and a lot of listening and stylistic learning happened there. Music school was like permission to apply everything you had absorbed.

When I moved to New York it became real life. In the early days I probably listened to music the least because I was focused on surviving the recession, getting a job and paying my bills. The music was in me but I was not listening to much.

When did headphones come into play, walking around New York with music in your ears?

Oh yeah, of course. They double as earmuffs.

“It’s like filmmaker friends sending secret links to movies and saying you can’t watch it on your phone. You hope people listen in peaceful environments but also running for the bus.”

When you’re working in the studio, how conscious are you of the physical space sound will eventually live in, whether between people’s ears or in their rooms?

I used to think about that a lot and get really confused by all the different mediums people listen on. Eventually you have to let it go because it changes too fast. People listen in the shittiest ways now. Car culture is gone. Headphones keep changing. No one is sitting in their room with a deck anymore.

I’m going to stop you for a second — I’m currently in a room with turntables and big Magnepan speakers. Your music sounds glorious in this space.

It’s like filmmaker friends sending secret links to movies and saying you can’t watch it on your phone. You hope people listen in peaceful environments but also running for the bus. It is futile to imagine how people will hear it.

Do you carve out time now to sit and listen to music, and how do you do it, headphones or a home system?

I am traveling so much that planes and transit are where I listen. I am always searching for something to listen to that will not annoy me. At home I have a nice setup, but I am often oversaturated so I read or watch things instead.

What are you listening to right now, or listening for?

On this tour I listened to Annahstasia’s album Tether a lot, and this French Algerian musician named Remi Chabanel. I also went back to Nina Simone, especially Silk and Soul. Those records hold you down. They never get old.

Have you listened to Live at Newport?

Yeah. That one always gives me shivers.

Arooj Aftab plays at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills on January 24, 2026. Info and tickets here.