In conversation with Small Medium Large, a new quintet from the burgeoning new West Coast jazz & improvised music scene. In 2018, LA-based jazz and post-rock guitarist Jeff […]

Listening to John Martyn: Interview excerpts, clips and inspirations

Ever the explorer, the British folk guitarist and songwriter carved a singular path, mixing jazz, dub and Echoplex textures.

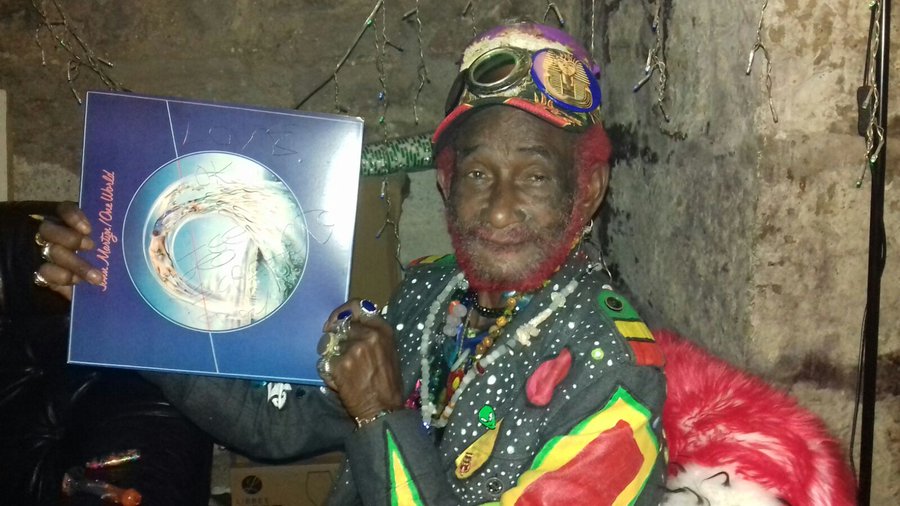

Few testimonials carry more weight than that of the King of Heaviness, Lee “Scratch” Perry. Asked about one of his 1970s British collaborators, the dub producer replied with a compliment and an observation:

“Great fun to work with, John Martyn. He’s willing to hear, willing to listen, try anything… And he love to drink rum…”

Born in post-World War II England, Martyn arrived at precisely the right moment, at least from the perspective of a young man obsessed with folk music, the acoustic guitar and experimentation. He turned 20 in 1968, just as kindred spirits across the UK were making an impact in clubs and at festivals.

His output over the next four decades would be as varied as it is inspired. We’ve delved into Martyn’s deep discography; in fact, the listening session we’re hosting at ISC NYC this afternoon will be curated by Dane Majors, who contributed to a primer for ISC on Martyn’s records you should read called Sunshine’s Better: John Martyn Deep Cuts, B-sides and Rarities.

Those curious about this era might want to pause this overview right now and grab a copy of Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music, by Rob Young. The most in depth account of that era, it traces Martyn’s rise alongside kindred spirits including Richard Thompson, Martin Carthy, Sandy Denny, Nick Drake, Roy Harper, and dozens more.

Here’s a brilliant excerpt on Martyn from the book. The scene: in front of a stereo in a London flat where “a rotating cast of characters,” including a young woman named Robin Frederick (who had a thing for a soft-spoken mutual friend named Nick Drake), had just gotten a copy of the first album by the Incredible String Band.

Writes Young:

In the moments when the needle was lifted off Martyn’s copy of Sgt Pepper, and he left off practising on his newly acquired sitar, the pair would pick up their guitars and trade songs. Frederick brought a souvenir from France: “Sandy Grey,” a song she had written inspired by her feelings about the indistinct, in-between colours of Nick Drake’s elusive persona. “[Drake] asked me to meet him one evening at La Rotunde, a cafe where we all used to hang out,” recalls Frederick, over forty years later. “I showed up and waited for him but he never turned up. One of his roommates was there; whether Nick sent him or he just happened to be there, I don’t know. I remember [Martyn] making excuses for Nick – ‘Oh, that’s just the way he is’ – but I wasn’t having any of it. I waited for a long while at the cafe and then left when I decided he wasn’t coming. My pride was hurt. I remember being quite upset about it. In ‘Sandy Grey’ I cast Nick in the role of wandering, rootless, fatherless boy.”

Continues Young:

Martyn had not yet met Drake, and Frederick never told him about the origin of the song, but some aspect of it clearly touched Martyn’s nerves, for he recorded ‘Sandy Grey’ on London Conversation, the LP he made as the first white solo performer Chris Blackwell contracted to Island Records. ‘Those were the days of the dancing, whirling dervish,’ Martyn recalled. ‘I breezed through them.

Martyn said yes to a lot of interviews over his life, and when he did he was a quote machine. In what turned out to be his final interview, he spoke to Uncut. He didn’t pull any punches:

Uncut: Given that you’ve often criticised British folk, how did you feel to be awarded a Lifetime Achievement at this year’s BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards?

Martyn: [Cackles] I’ve never been critical of the British folk scene. I just don’t like when they put a 4/4 against a lovely traditional tune. Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span, go away! It’s like a cross between a swan and a duck – the rhythm section being the duck. As soon as you put that bass and drums on it, it coarsens it and changes the nature of the music and makes it into something quite unacceptable to me. I love Martin Carthy and Dick Gaughan, I love proper folk music – Eliza Carthy, The Watersons and all that stuff, but as soon as they put a fucking 4/4 beat on the back of it, it’s no good at all. A purely commercial move.

In 1973, Martyn gave an interview to NME. The guitarist went on at length about the lack of heart, of sweat, of real-life experiences, in contemporary music of the time:

It’s all too easy for sensitive people to prostitute themselves in this society but pandering to the establishment is quite simply an evil choice. It’s not good that someone like me should earn £250 a night when my father has to sweat his guts out for his £30 a week. But I’m not into bloody revolution, I’m interested in watching what’s going on very carefully.

Bowie’s a poseur, too. I don’t think he’s lived a quarter of the things he sings about and, to me, living it is crucial. Life is real. Life’s in earnest. It isn’t a play. People are real and they have hearts, whether they realize or not. It’s no battle to get up there and sing whatever’s in your head at the time, but it’s a whole other scene to lay your heart on people. I want to be able to take myclothes off in front of everybodyand say: ‘See? I’m just likeyou’. That is the happeningthing, not whatever bullshit the papers tell us. It’s always beenwhat’s happening and it always will be.

Below, a few of the Martyn records that we’ll be playing as part of our weekly Monday listening series at ISC NYC.

John & Beverley Martyn - The Road To Ruin (1970)

The Road to Ruin marks a pivotal stepping stone in the multi-faceted career of our patron saint John Martyn. Not only was it the last collaboration with his then-wife, vocalist and songwriter Beverley Martyn, it was also the first album to show signs of Martyn’s defining sound, the heavy jazz and effect driven folk of his later records. Andy Childs of cult brit-rock magazine Zigzag wrote in 1974, “The Road To Ruinstands apart from other John Martyn albums… it enjoys distinctly jazz instrumentation in what is basically a rock format.” John later recalled of this transitional shapeshifting period saying, “By the time Beverley and I recorded our second album my ears were opening a little and I was listening to a lot more music. I’d been to a lot more gigs and was hanging out with other musicians non-stop. I was exposed to more music every day through other people’s record collections, gigs they took me to and gigs I went to on my own.”

In essence, the album is a beautiful folk-rock record played by an all acoustic jazz lineup. Though the album as a whole is fully a masterwork, there is need of mentioning A3 Auntie Aviator. Wholly unique in that it’s somehow beautiful and also quite terrifying (much like the cover image), the track is a stunning mix of ghostly vocals, improvisational piano, and wild guitar effects that all come together to form a swirl of jazzy psychedelic darkness. Like a bad trip you, for some reason, don’t want to end.

The Road to Ruin unfortunately also marked the beginning of John’s descent. It was recorded in the last years of John and Beverley’s idyllic happiness as a couple. Soon after John would blossom as a solo artist, composing his most praised and renowned work but at the dark expense of traveling deeper into alcohol, drugs, and a violent depression that would ultimately dominate his life. — ISC Team

Inside Out (1973)

Inside Out has been described by John Martyn as “everything I ever wanted to do in music… it’s my inside coming out.” More experimental and free-form than his previous releases, the album showcases John slowly turning electric and jazzy. Martyn’s muted, almost submerged electric guitar solo on opener “Fine Lines” is breathtaking and really shows his skill as a guitarist. Ex-Pentangle member Danny Thompson shines throughout with his warm double bass playing. Martyn: “I think I’ll always use Danny Thompson because he’s got a real feel for my music and I’ve got a real feel for his.” — ISC Team

Solid Air (1973)

Cited as being an entry point to genres such as trip hop and ambient, Solid Air is undoubtedly John Martyn’s magnum opus. A true balance of dark and light, the album name and title track serve as a dedication to his friend and label mate Nick Drake whose noticeable depression was of deep concern to him. The record plays through a various array of emotions and expressions, bringing you up before letting you stay too low with its juxtaposing track sequencing. – Jonny Garciaros

One World (1977)

When, in 1976, Island Records’ Chris Blackwell suggested that Martyn head to Jamaica to work with Lee “Scratch” Perry, the guitarist did so, resulting in one of Martyn’s greatest works. Here’s Dane Majors on what happened next:

Even Martyn himself was unsure how much time he actually spent at the Black Ark camp and in Kingston, stating “several weeks” in one interview and in a later one “several months.” Debauchery aside, John admitted it was a necessary journey, saying, “I honestly believe I would have gone completely round the bend had I not gone and done that.”

Martyn returned to Hastings reinvigorated by reggae rhythms, the atmospheric, drowned-out sounds of dub and began plotting his own imaginative ideas for production. Finally putting to rest his experiments in Arabic and Moroccan scales that he clung to in the Inside Out era, he worked out a new dub-informed approach. With the help of two small drum machines and his Echoplex, Martyn laid down his first recordings in almost a year and composed the demos for what would be One World. He sent them to Blackwell, who immediately upon receiving them knew that Martyn was onto something special. Blackwell created a proper venue for the recordings by assembling a conceptual studio at his countryside Woolwich Green Farm in West Berkshire.

The small rural farmhouse converted on the estate was buried in the middle of a flooded gravel pit surrounded by water. Blackwell hired Phil Brown, the Island Studios engineer turned outdoor recording pioneer, to design a unique recording outdoor/indoor studio. With his help, they converted a 12×15 horse stable into the main studio and then mic’d the entire expanse, an intricate system with a live feed across the lake so they could record in the open air and purposely pick up the surrounding ambiance, most notably the movement of the water.

“That was possibly the seed of recording One World that way,” Phil Brown recalls. “I don’t think at this point there was any great plan about using the water. That just kind of evolved once we got set up and realized the possibility of the place. The ten days we spent at Chris’ recording it, we were recording outdoors, pumping whatever John was playing through a PA system and across the lake and miking it up, because of that aspect, it rather made the thing magical.”

The atmosphere of the One World studio, Blackwell recalls, was like “a circus.” Martyn and his band, including ex-members of Traffic, Gong, Fairport Convention and Pentangle, all lived in the small 12×15 stable during the recording process. At the same time, a large cast of characters visited. Friends, family, musicians and, most notably, a friend from Jamaica. It’s at this rural English countryside barn that “Scratch” and Martyn reunited to record their most famous collaboration and their only co-written effort, “Big Muff.”

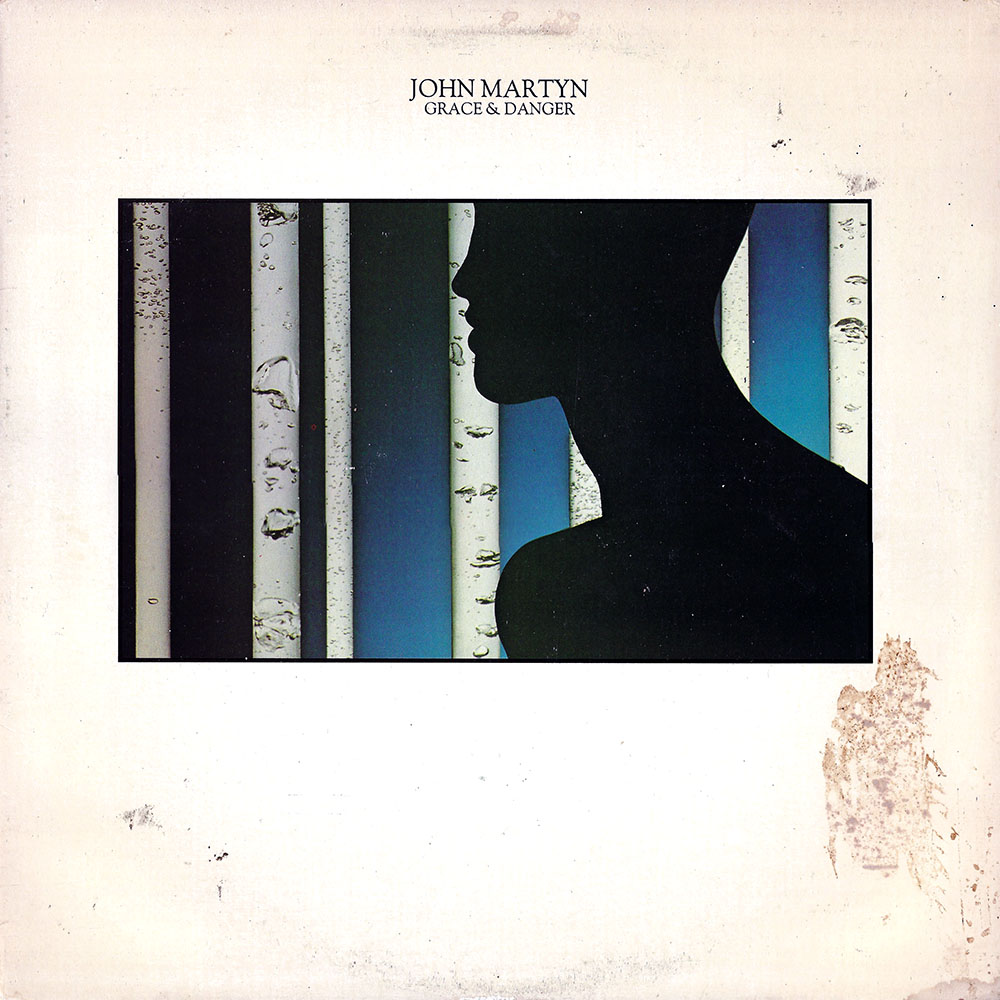

Grace and Danger (1980)

Reportedly shelved for a year by Island Records’ Chris Blackwell because he found the songs too personal and unsettling, Grace & Danger is a heartbreaking portrait of John Martyn’s failed marriage with his longtime partner and previous collaborator Beverly. Later reflecting on the situation, Martyn said, “I freaked: ‘Please get it out! I don’t give a damn how sad it makes you feel – It’s what I’m about: direct communication of emotion.’” The album features Genesis drummer Phil Collins, who was spending a lot of time with Martyn during this period as both musicians were going through painful divorces, along with Wham! musical director Tommy Eyre, and bassist John Giblin, who played with Kate Bush and Scott Walker. With melodic fretless bass, synthesizers, and shades of R&B and fusion, Grace & Danger remains one of Martyn’s best from his ‘80s period. — ISC Team