Good Smooth Jazz from Pat Metheny, 101 North (George Duke), Craig T. Cooper, Ben Tankard, and more! One of the most hated and controversial genres around, Smooth Jazz […]

How Miles Davis set the jazz world on edge with ‘On the Corner’

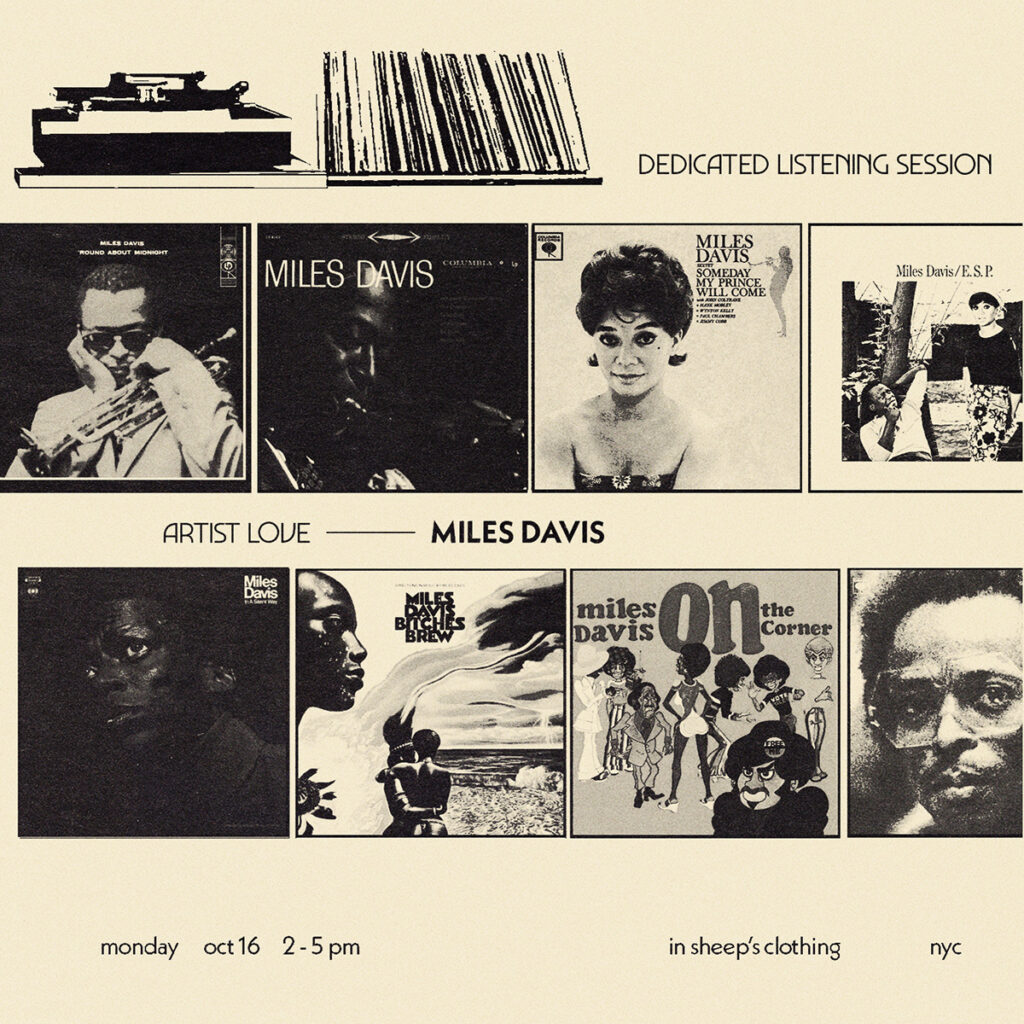

For Monday’s dedicated listening session, we’re going deep on the trumpeter’s expansive creative output.

“Repetitious boredom.” “An insult to the intellect of the people.” “Nameless, faceless go-go music.”

Released in 1972, Miles Davis’s On the Corner accomplished that rare feat in popular music: pissing off critics and mainstream listeners alike. Eight Davis-penned songs inspired by the trumpeter’s newfound love of the Last Poets, James Brown, Sly & the Family Stone’s whole thing — as well as Bach and Stockhausen — and featuring Davis running his trumpet through a wah-wah pedal, the album was greeted not with mere ambivalence or curiosity, but active disdain. A young Eugene Chadbourne, perhaps best known for his invention of the electric rake (and being a killer guitarist), described it at the time in respected Canadian jazz magazine Coda as “pure arrogance … like coming home and finding Miles there, his fancy feet up on your favorite chair.”

Fifty years later, On the Corner is considered a jewel in Davis’s discography, one that not only showcases the trumpeter’s increasingly experimental, minimalist and electrified approach, but does so through the communal efforts of a band that features Dave Liebman (saxophones and flute), John McLaughlin (electric guitar), Michael Henderson (bass), Herbie Hancock (keyboards), Chick Corea (keyboards), Jack DeJohnette (drums), Billy Hart (drums), Colin Walcott (sitar), Don Alias (percussion), James Mtume (percussion), and others.

On Monday at In Sheep’s Clothing NYC, we’ll be celebrating the recorded work of Miles Davis during our weekly dedicated listening session. Devoted to hearing music at proper volume on high-fidelity gear, the three-hour deep-dive offers a chance to get lost in music with kindred spirits. And On the Corner sounds particularly brilliant on a great system.

“What I was playing on ‘On the Corner’ had no label… It was actually a combination of some of the concepts of Paul Buckmaster, Sly Stone, James Brown, and Stockhausen.”

Davis had started working with electricity, a polarizing detour that left purists in the dust, a few years prior. He did so as his success grew and the concert halls had gotten bigger, and due in part to his affinity with the work of Jimi Hendrix.

“Before that I had bought a real cheap sound system that was all right for the clubs I was playing in at the time, but it wasn’t good for the big halls, because nobody could hear each other,” Davis writes in his 1989 book with Quincy Troupe, Miles: The Autobiography. “So the sound just kept getting higher because when it’s higher you can make people feel things better. “

He continues:

That’s the way electronics came to me. First I got a Fender bass, then a piano, and then I had to play my trumpet against that. So then I got an amplifier hook-up with a microphone on my trumpet. Then I got the wah-wah to make me sound more like a guitar. Then the critics started saying that they couldn’t hear my tone anymore. I said, Fuck them. If I don’t play what the drummer wants then he won’t play for me. If he can’t hear me, then he can’t play. That’s how the groove thing got started with me. I started playing against all of that.

The approach bore fruit when he embraced the shift and started acclimating his muse to it.

When I started playing against that new rhythm — synthesizers and guitars and all that new stuff — first I had to get used to it. At first there was no feeling because I was used to the old way of playing things like with Bird and Trane. Playing the new shit was a gradual process. You just don’t stop playing the way you used to play.

On the Corner was recorded in New York over two sessions in the summer of 1972 at Columbia Studios on East 30th and produced by Teo Macero. Notably, one attendee at the sessions wasn’t a player, but the composer and arranger Paul Buckmaster, who was staying with Davis at the time. Buckmaster is best known for his work with David Bowie, The Bee Gees, the Grateful Dead, and others. Davis explained it in Miles.

I had gotten into the musical theories of Karlheinz Stockhausen, a German avant-garde composer, and an English composer who I had met in London in 1969, Paul Buckmaster. I was into both of them before I did On the Corner and, as a matter of fact, Paul stayed with me during the time I was recording. He was also in the studio. Paul was into Bach and so I started paying attention to Bach while Paul was around. I had begun to realize that some of the things Ornette Coleman had said about things being played three or four ways, independently of each other, were true because Bach had also composed that way. And it could be real funky and down.

Davis noted in the book that one of the first times he met Sly Stone, the bandleader gave him two records, one by his own band and the other by Rudy Ray Moore, a.k.a. Dolomite.

Davis opened up about his aim with the 1972 Columbia release:

What I was playing on On the Corner had no label, although people thought it was funk because they didn’t know what else to call it. It was actually a combination of some of the concepts of Paul Buckmaster, Sly Stone, James Brown, and Stockhausen, some of the concepts I had absorbed from Ornette’s music, as well as my own. The music was about spacing, about free association of musical ideas to a core kind of rhythm and vamps of the bass line. I liked the way Paul Buckmaster used rhythm and space; the same thing with Stockhausen.

Not everyone dismissed On the Corner. Writer Ralph Gleason reviewed it alongside Santana’s Caravanserai in a review for Rolling Stone, calling it “music of the streets.” He continued:

… and as such it has the throb of the street as well as the beauty of a rose in Spanish Harlem. It is music which celebrates street life as well as the beauty of life itself, and it brings together (and celebrates the individual beauty of the rhythms of) many different cultures. Even the guitar sounds of David Creamer and the keyboards of Herbie Hancock and Harold I. Williams are utilized in the creation of a lyric feeling and lyric sound without laying them out in linear fashion. This music is more about feelings than notes, as Donald Ayler once remarked.

Writing of his efforts at creating a fusion of jazz, rock and funk, Davis stressed that embracing the new and the unfamiliar takes time, whether you’re a conservative jazz critic, a rake-playing rule breaker or some combination thereof.

“You don’t hear the sound at first. It takes time. When you do hear the new sound, it’s like rush, but a slow rush,” he wrote.

Listeners at ISC NYC on Monday will be able to absorb Davis’s evolution, from his late-1950s bop and cool jazz records Round Midnight and Kind of Blue to his mid-1960s modal jazz recordings ESP and In a Silent Way to his early 1970s fusion masterpiece Bitches Brew and beyond.

Miles Davis dedicated listening session queue for Oct. 16 in New York:

Round Midnight (1957)

Kind of Blue (1959)

Someday My Prince Will Come (1961)

E.S.P. (1965)

In a Silent Way (1969)

Bitches Brew (1970)

On the Corner (1972)

Get Up With It (1974)

Where: In Sheep’s Clothing NYC, 350 Hudson Street (enter on King)

When: Monday, Oct. 16 from 2-5 p.m.