Try fitting a cathedral in a suitcase. That’s the quiet determination behind American Masters turning its lens on Sun Ra, an artist whose life and work feel so […]

Now Jazz Now: Thurston Moore, Byron Coley and Mats Gustafsson Map the History of Free Jazz

“…just three guys who really like records trying to make a case for their collective obsessions,” writes Coley.

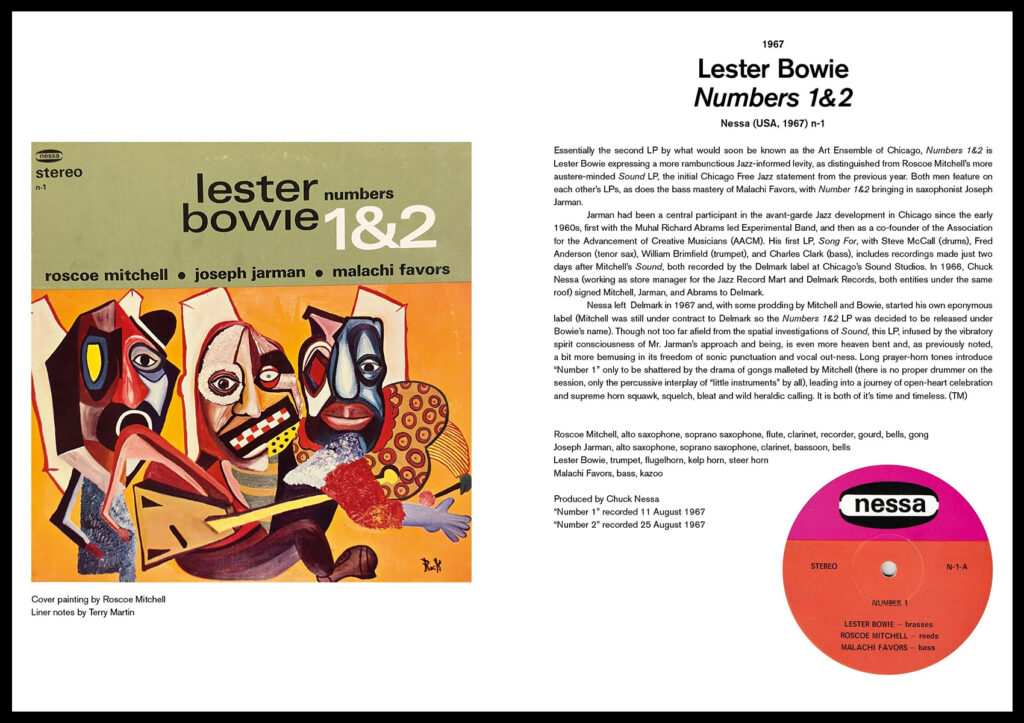

The just published book Now Jazz Now took decades to arrive. Co-authored by Byron Coley, Thurston Moore and Swedish saxophonist and collector Mats Gustafsson, the book grew out of a lifetime of shared listening, record hunting and argument about free jazz and improvisation, a music that has always lived on fragile paper trails. Release notes call it “a book for all adventurous music lovers, whether ravenous record collectors, avant-garde jazz enthusiasts, students of radical culture, or simply curiosity seekers in wonder to this music’s illustrious history and lineage.” Coley recently traced the project’s roots in a Forced Exposure essay called Not One Fucking Bow Tie, which sketches a history made up of missed chances and stubborn persistence.

One of those chances came in the late 1980s, when Doug Wygal at Sony, Coley writes, “reached out to me and Thurston because we were the only people he knew at the time who were seriously obsessed with collecting and documenting free jazz.” The plan to rescue and reissue the ESP-Disk’ catalog, which issued essential avant rock and free jazz by artists including Sonny Simmons, Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, Pharoah Sanders but maintained messy contracts, collapsed under unpaid royalties and missing documentation, but it left Moore and Coley with a lasting sense of how easily this music could slip through the cracks.

Those were also some remarkable years for collecting jazz vinyl. “This was an era where record stores were full of amazing, as-yet-unheralded LPs,” Coley writes, when you could still pull original Sun Ra records for pocket change. That kind of access fed Moore’s imagination and Coley’s archival instinct, laying the groundwork for what would become Now Jazz Now.

The project finally snapped into focus when Moore met Gustafsson in the 1990s. “From that point onward… it was always as a three-person project,” Coley writes. When COVID hit, they set the frame at 1960 to 1980 and began listening their way through thousands of records. “Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity was untouchable,” Coley notes, “but everything else was up for discussion.” The result is not a canon so much as a map, shaped by influence, geography and the deep personal pull of certain sounds.

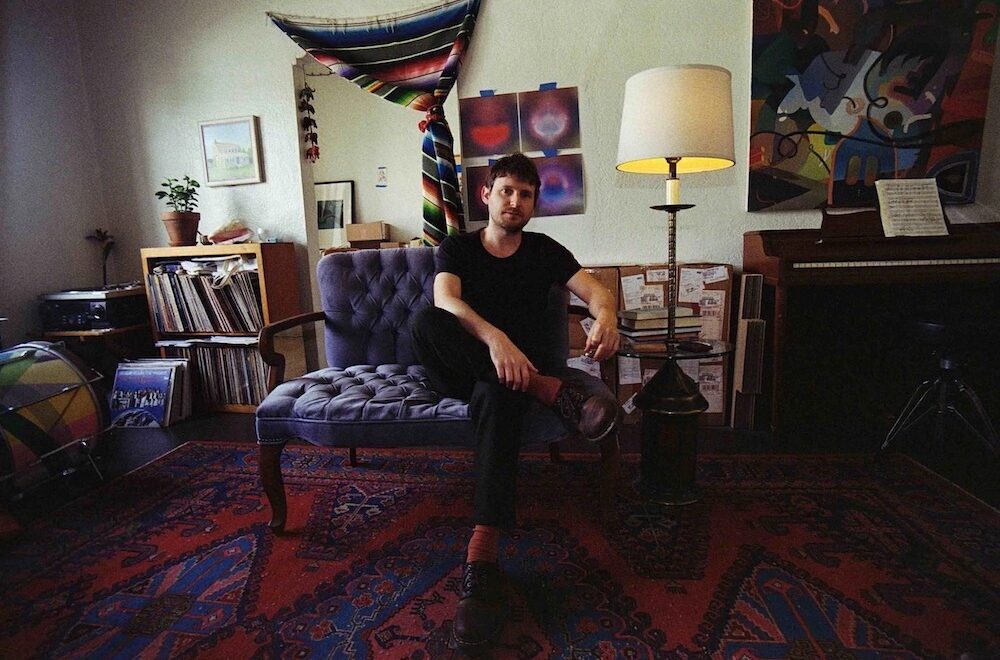

That conversation rests on a much longer one. The friendship between Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore and Byron Coley stretches back more than forty years. As the Bull Tongue columnists for Arthur, they made their shared listening public, tracing the edges of free jazz, noise and outsider music as it happened. Coley had been writing Moore into a broader underground lineage through Forced Exposure — the zine that spawned the essential online vinyl store — Spin and Sonic Youth liner notes, while Moore treated Coley less like a critic than a fellow traveler.

Moore and Coley have spent decades circling the same music, one as a musician, one as a writer and archivist. Now Jazz Now is the clearest snapshot of that long, obsessive conversation.