Let’s talk about Roberto Musci, the Milanese experimental composer whose work both alone and with kindred spirit Giovanni Venosta starting in the 1980s has been gaining attention and […]

Planet Q: Tomoki Sanders & Kyoko Takenaka on creating a musical safe space for qtpoc folx

Enter the world of Planet Q, a “beautiful, secluded safe space” lovingly hand-crafted by artists Kyoko Takenaka and Tomoki Sanders.

A little over a year ago, Pure Person Press‘ Angela Lin sent me a link to an unreleased album. “This is from my friend Kyoko… I really love it. Let me know what you think!” Curious and fully trusting of Angie’s musical instincts, I hit the link right away. As the tracks played as one continuous album stream, it soon became apparent that an entire universe of sound had been captured here. Lovingly handcrafted, the music felt honest, filled with “wearing your heart on your sleeve” type energy, and complete with a fully formed artistic vision. Track titles were hand drawn in calligraphy, psychedelic visuals featured homemade clothing, and lyrics in both Japanese and English pointed to a uniquely Japanese American (Nikkei) aesthetic.

As I learned more about the project, the voices and characters of the two singular artists behind the music started to come into focus. Kyoko Takenaka (they/them) is a bilingual, first-generation Nikkei Japanese American performer & creator. A multi-disciplinary artist, Kyoko channels the diasporic experience in their work across film, butoh dance, music, and visual art. Tomoki Sanders (they/them) is a multi-instrumentalist, producer, and artist. They are the child of the late saxophone legend, Pharoah Sanders, and their mother is a deep music-lover from Japan. They’ve been playing piano, drums, percussion, alto and tenor saxophone from about as early an age as you could possibly play those instruments.

“Our aim was to create a really beautiful, secluded safe space for ourselves as qtpoc folx – a planet where we both belong – and to make music as we created the space.”

The fact that both artists identify as non-binary should perhaps come as no surprise after listening to the music. The songs move fluidly between genres, often defying categorization. From the liner notes: “At various times the tracks move like Dilla pieces, at others like Terry Riley explorations, like Flying Lotus or Milford Graves or Alice Coltrane meditations. But every time you think you’ve got the sound figured out, it hits from another angle.”

Tonight, Kyoko and Tomoki will perform Planet Q for the first time in Los Angeles at In Sheep’s Clothing HQ. The show will feature live instrumentation, movement, and butoh dance along with a rare DJ set from Pure Person Press’ Angela Lin. A few tickets are still available: https://link.dice.fm/Eb67d4ef69f4

Planet Q is out now on vinyl via our label In Sheep’s Clothing Hi-Fi Selects: https://insheepsclothinghifi.com/product/kyoko-takenaka-tomoki-sanders-planet-q-lp-pre-order/

In anticipation of the show and in celebration of this gorgeous album, I caught up with Kyoko and Tomoki over Zoom to learn more about their musical upbringings, jam spaces, cooking while making music, and what they’re currently listening to.

Hello Kyoko & Tomoki! Both of your parents were jazz musicians. Can you share a bit about your musical upbringing?

Kyoko [they/them]: I grew up going to a lot of Japanese jam sessions in Boston at Berklee College of Music, where Tomoki went as well. My dad taught there so I was always tagging along and taking voice lessons from the jazz students. From around age six or seven I was singing jazz classics. “Like Someone in Love” was one. “Misty,” “God Bless the Child,” etc. — things from the real book. I was obsessed with Billie Holiday at a young age, mostly probably because of how she spoke so candidly about abuse and heartbreak, things I observed from a young age. So that was definitely a big part of my life, but I also felt like it took me a long time to come back to music and so-called jazz because of my relationship with my dad. Growing up with a father who was a musician and wasn’t that present in our family’s life, I’m always conscious about how to be an artist and also show up as a human being in terms of family and community.

I took a break from music after my dad left. I felt that the rest of my family felt like art and music was a very selfish thing to do because of him. I swayed heavily away from jazz and started listening to white emo/indie music: Pavement, Cap’n Jazz, Owen Pallett, Joanna Newsom, Yeah Yeah Yeahs. When I was 15, I bought my own guitar and started writing songs in my bedroom, going to open mics, and things like that. It wasn’t really until I moved to New York that I started to feel like music was something I was allowed to do… My name is Kyoko, which means “vibrations of sound child.” It was a name that my dad picked out and my mom didn’t really have a say in that naming process. So I think when I was living in New York, it was really all about reclaiming my name for myself and the journey in that.

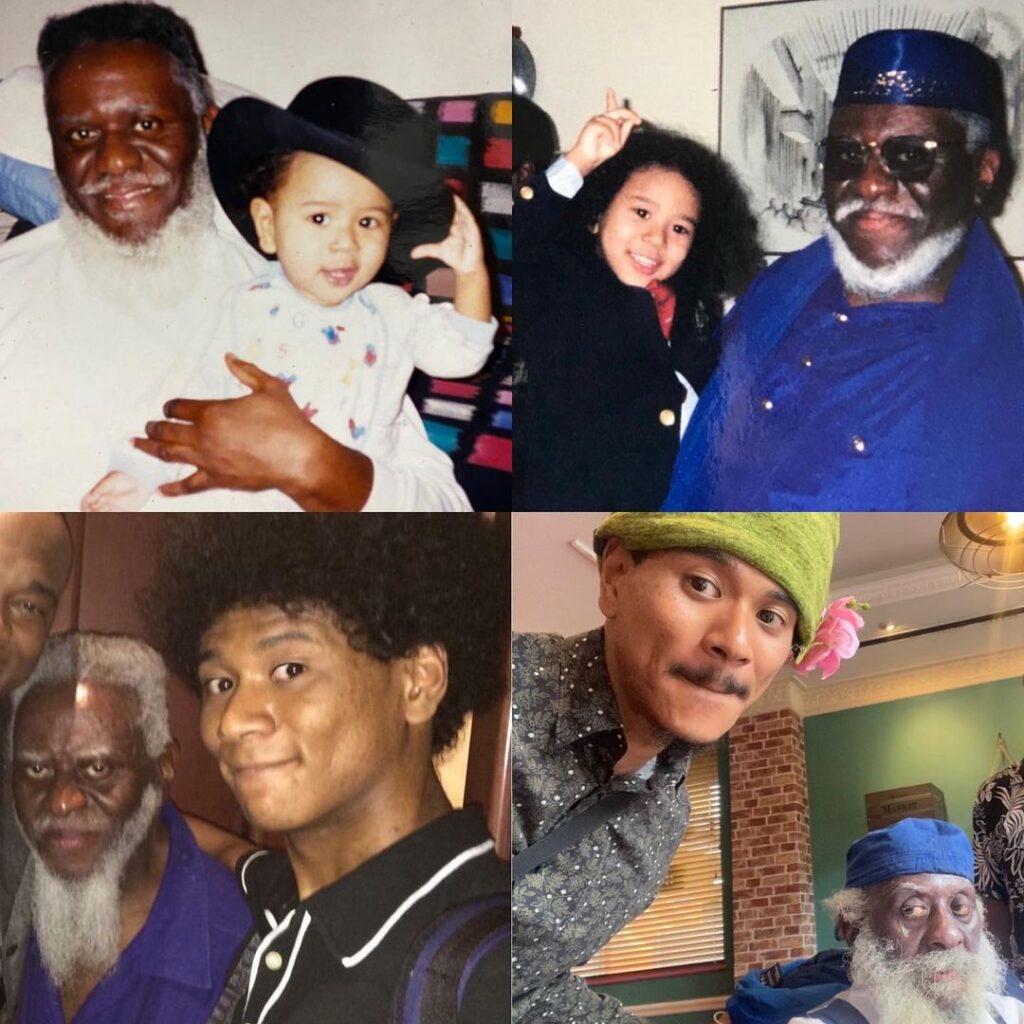

Tomoki [they/them]: I was born in New York City in 1994. Musically, it was a very luxurious experience for me, and it kind of took me 28 years to really understand that luxury. When I was a kid, it was just like, “Oh, daddy’s on stage,” and I was expecting every kid’s parent to also play an instrument. So that was kind of my oblivious reality. For me personally, my dad happens to be one of the most influential and appreciated saxophone players in the world. I’m very grateful to have had, in my opinion, the coolest dad on the planet.

“What I learned from [my father] was to be honest to your creativity and be honest to every single input in your mind, soul, and spirit… Make sure there’s no BS on your end, tap into the music, focus, and have fun.”

Tomoki Sanders

I’ve been listening to his music since I was out of my mom’s womb. I’ve also been growing up with music from the people around him, like Alice Coltrane, John Coltrane, Art Blakey, George Adams, Don Pullen Quartet, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, etc. Those are my first musical roots. Later on, my sister was in her room listening to Destiny’s Child, S Club Seven, N’Sync, Nirvana. She was into mainstream pop and rock music, while I was just listening to the most Afro-centric jazz records. My upbringing was listening to all of that – a combination of spiritual jazz, Michael Jackson, Earth, Wind and Fire, everything from jazz to hip hop, pop, and rock music. So I kind of consider myself a music mutt. I was also really into video game music, like Sonic the Hedgehog, Super Mario soundtracks, Pokemon, and anime music. Pretty much anything musical has been very attractive to me since I was a kid. I wanted to stretch out and appreciate every single kind of music that was in my surroundings. Keep my ears open. Keep my head open.

As a second-generation musician, what lessons from your father have you taken with you on your own musical journey?

T: I’ll say this about my dad, and I think a lot of people who worked with him will say the same thing. He doesn’t talk much. He’s a very quiet person. He’s not really the person who wants to give you a whole sentence of how he feels about anything, what he’s listening to, or how he feels about certain music. He’d be like, “Oh, that’s cool, that’s nice,” or he’s like, “Nah.” He can say one word and that’s profound enough to really hear what’s up in his ears. What I learned from him was to be honest to your creativity and be honest to every single input in your mind, soul, and spirit. Whenever you’re on stage, when you play any kind of music, just be truthful to the music, stick with it, and serve the music. That’s the method I have to this day. Make sure there’s no BS on your end, tap into the music, focus, and have fun.

When I was trying to learn saxophone, he told me to check out Sonny Rollins before checking out John Coltrane, but I was kind of impatient. When I was four years old, I would listen to Giant Steps from top to bottom, like it’s a whole video game. I listened to a lot of Trane’s records. Actually, right now, I’m seriously tapping into the Sonny Rollins vibes. He’s one of our last few living legends who’s really seen the whole history of the music being with Charlie Parker and then John Coltrane, Monk, and then playing disco type funky music. But yeah, I’m truly grateful for how dad taught that you gotta start from something to really take you to that high level of performance and mastery.

K: For me, growing up as the child of a working jazz musician, somehow I thought filmmaking or videography would be a more responsible choice. When I was studying filmmaking and doing freelance videography, I would do a lot of work for the New York Guitar Festival or other music-related projects. I was backstage in all these spaces and started having a lot of deja vu moments from childhood; but experiencing it on the other end. I saw a lot of different dynamics around patriarchal structures. Seeing those dynamics from a different angle was interesting. I think now I’m taking all those experiences and reincorporating them into my own space as an artist and figuring out what I can do differently and how to create different spaces for other queer/femme folks.

“After playing a very mature technical and incredibly breathtaking solo, [Tomoki] will shout: ‘We’re here and queer, still here and queer,’ and it put a huge warm smile on my face and made me feel so at home.”

kyoko takenaka

On that topic, Kyoko, you've spoken about how music and jam spaces can be uninviting to queer/femme artists and how Tomoki has been a force for change within these spaces. Can you share some of your experiences?

K: When I first moved to New York, I started my own group from a few folks I met literally on the streets of downtown brooklyn when I first moved – it was an Afrobeat-inspired rock band. When we ended the group, I was on my own again and started going to jam spaces. I had longer hair then and I was way more femme. All of these spaces were ruled by cis-men. I would show up as a musician, but it always got to the point where their interest was somewhere else. That dynamic was always there. Even though I would try to jam with people, create different projects, no one really took me seriously. I ended up getting so jaded and upset that I actually moved out of New York and just thought, “I can’t do music and I can’t continue to try to prove myself in these spaces.” So I moved to London and it was there that I found my queer music community – some of the most talented people I have ever met, who genuinely do the work also in creating accessible spaces for their community and speaking out on social issues – and not having their activism compromise their music or talent either.

When I met Tomoki in Japan, it was just extremely genuine and they really wanted to collaborate as artists. We did a bunch of performances in Japan, and when I moved back to New York they invited me to perform at their solo gig. Re-entering New York in that way really helped take off my jadedness from the music scene. I think they really are just such an international gem and they’re shining in these spaces. That is so refreshing and something that I’ve never seen before. They show up to every gig with this really fresh, almost teenage energy and just unapologetically will be like, after playing a very mature technical and incredibly breathtaking solo, will shout: “We’re here and queer, still here and queer,” and it put a huge warm smile on my face and made me feel so at home.

They’re always uplifting other queer artists. When they did the showcase at NuBlu, they were so conscious about that and brought other queer and intersex artists. No one was compromised in their craft and it was truly like, “Everyone’s really talented here, some happen to be queer, and I’m changing this space.” When they interact with generational heroes, I can see the way that all of those elders are forced to change – they make it irrelevant to be homophobic or patriarchal. They’re really like, “That’s just not what’s happening anymore, and that’s just not what’s cool. So you better get with it or you’re going to feel left behind.” I believe in that confidence, I believe in that pulse so strongly and energetically. I’m really grateful to put out this record with them and put out more of this energy, but I’m also just excited for what they’ll do beyond this project in their solo work and the way they’re going to change the scene and make it more accessible for different folks in the future to step up and be the best at their craft.

Getting into the music on the album… “Home” is mentioned on the album opener. You’re both constantly traveling between places (NY, LA, Tokyo). What is “home” for you?

T: There’s a jazz standard called “A House is Not a Home” and I’ve been learning that mentality as an adult right now. Sometimes a house doesn’t feel like a home. When you’re home, you need a sense of safety, freedom, and some sort of security on a mental, spiritual, and health level. It has to be something that makes you feel you can be yourself in any moment. You want to feel grounded. I think that’s what I’m learning about what the feeling of home is. You want to have that grounding, earthy kind of feeling to it as opposed to bouncing wall to wall. I think that’s what home is to me.

K: “Home” is a theme that keeps coming up in my life. I made a short film about it that went viral called “Home.” I’m constantly in multiple cities at the same time trying to find it, trying to define it with myself. Something that always keeps coming back to me, is that home has to be inside of you. It’s how you interact with your environment, for sure, but you have to feel that for yourself. When Tomoki and I were writing that song, “My Tender, My Sweet, My Loving Home,” we were both trying to ground ourselves in the current space we were in, which was in a NY apartment.

The first song on the album is really this prayer and protection for ourselves. We wanted to really create that auditory space, bask in it, feel it, and to make it like a promise no matter our physical or mental headspace to be able to know it and return to it at any time. A feeling inside of you. It started because I think Tomoki was feeling heated after a phone conversation. So I was like, “Let me lead us through meditation. Remember, you can always hug yourself and hold yourself. When you can’t feel other people’s touch, just remember you have yourself.” So I physically made them hug their body and I just kept repeating, “I am present with my tender, my sweet, my loving home.” Home is something that we walk with, but we have a choice to create that space for ourselves.

“Those experiences that we share in that in-between space really make me feel so alive and passionate… I’m allowing myself that fluidity where I’m allowed the totality of a human experience.”

Kyoko Takenaka

It seems like you really created that feeling of “home” while making this album. I love that you also cooked together while making the music. Can you each choose one track and share what dish it sounds like?

K: The easiest one would be “neba neba.” We both love natto (fermented soybeans). We ate it almost every morning with rice. Texturally, “neba neba” was really about this sticky universe and how to create that auditorily. It started with my guitar and looping things, and we just never left that space. We ate natto, closed our eyes, and tried to be in the texture of natto, imagining a whole world where the floor is not grass, but natto. My feet were like jaws and every time I walk, I’m eating and feeding myself with every step. We thought that would be such a great world. The string that’s created when you eat natto can get really long. “neba neba” is the word for that specific texture in Japanese. I love eating anything that’s that texture.

T: Personally, I see “竹” as the bamboo shoots that you can get on ramen. People typically think of bamboo as an alternative for a wooden product, but you can also cook bamboo, chop it up and put it on your ramen. It tastes bomb! “Rice Cooker” was also written during our cooking time. You can hear Kyoko’s voice making crackling sounds and I was playing the shaker. That’s my image of the steam that comes out of the rice cooker. It’s also the process of making rice, making sure it’s the right shape, temperature, and softness. Incorporating those ideas into the music was really fun.

I think making music while cooking can take you to a whole new level of how you see life. Sometimes when you write music, there can be thoughts like, “Oh will this sell a million copies? Can this song go off in the club?” But no, we wanted to write what we were seeing in our reality, and that was sitting at the same table in the living room eating natto, rice, raw eggs, kimchi, miso, soup, and Japanese curry. We were really just being as human as possible while making these tracks.

It’s by far one of the most authentic experiences I have ever had during the recording process. It’s also definitely about channeling our inner child as well, which, in my opinion, is the absolute best ingredient as an artist. All of my heroes who are no longer on this planet have had this inner child spirit in their music. I can hear a kid in their sound. Also, at the same time, I hear a grandparent. It’s really about tapping into being present and being vulnerable.

“It took me five or six years to recognize I have a different energy that was outside the whole cis-gendered male ideology. Ever since I was a kid, I was not the most masculine or feminine. I was somewhere in the middle.”

tomoki Sanders

You both identify as non-binary. What can you say about being non-binary and how it has affected your approach to art, music and this album?

K: I think being non-binary has kind of shaped my approach to life or what’s acceptable as an approach to life. It’s not a new concept and we owe so much of that to black trans folks who’ve really paved the way. As an artist, we’re often forced to choose an art form. Pick one and just do that. Growing up since high school or something, I couldn’t really pick one or decide. Even throughout college, I’d have a website of my visual work and then I’d have my music. I was constantly trying to get advice from professors about how to merge both and the answer was always to just pick one. I think generationally that’s something that’s changing, which is really great.

Now I see more and more artists that are multidisciplinary, but growing up, it did feel very binary. You’re either a musician or you’re either a photographer, you’re either in jazz or you’re either in rock, and you can’t just move around. You’re either going to be in pop, or you’re going to be in the underground scene, all these things. When I started training in butoh, that was something that really clicked for me. We were doing workshops where we’d be bending between two textures and finding a space where you couldn’t name if you were either texture. I realized, “Oh wow, this is actually how I live.” Duke Ellington has this famous quote: “The highest compliment is to be beyond category.” I think about that quote a lot not just in terms of music genres or mediums, but also just allowing myself to go to whatever gravitates towards me in whatever expression.

So often I have an idea or a vision for something, but it’s part dance, part music, and all of these puzzle pieces that come from different mediums. I’m always trying to bring it all together. I think just the word non-binary has allowed me to think about how there’s never this either or, like I’m just Asian or Asian-American. I think a lot of my feelings and my work and the things that are most prevalent in my life exist within that in-between space that’s unnamable. Those experiences that we share in that in-between space really make me feel so alive and passionate, or angry, or happy, or seen. I’m allowing myself that fluidity where I’m allowed the totality of a human experience.

T: So it took me five or six years to recognize I have a different energy that was outside the whole cis-gendered male ideology. Ever since I was a kid, I was not the most masculine or feminine. I was somewhere in the middle. There’s a feminine energy in me that I like to embrace and also a lot of masculine as well. Society wants to put you in a box based on your anatomy and that can feel enslaving in a lot of ways… It was truly a liberating feeling when I came out as non-binary. I came out in 2020 during the pandemic during a time when I was really trying to understand my own energy, spirit, personality, and of course, my sexuality. I think that being non-binary feels like there are no limits to who you are as a human being. There’s not just one way. There are so many ways to be non-binary because it’s your own story.

You have to build your own story individually, as opposed to finding materials from the media or Internet. It has to come from your inner spirit, and hopefully people can understand who you are as a human being. Of course, you might find someone you can feel connected to emotionally, physically, or spiritually, but it’s more important about what’s inside than what’s between your legs per se… I think meeting Kyoko was an absolute eye-awakening experience for me because they were non-binary as well. It was kind of like a match made in heaven, in a lot of ways. I feel like I found someone who’s like my twin and able to really express who they are as a human being and artist. With this project, I really hope the listener can hear and understand that this is a true connection with two human beings. Kyoko impacted my life, and I hope I influenced or inspired them as well. It’s like a mutual respect, love, and inspiration to levitate our spirits, energies, and our life. This project is the true manifestation of who we are individually, and who we are as a collective.

Kyoko, calligraphy is another one of your passions. What was your process in creating the calligraphy and artwork featured on the album cover and gatefold?

K: When I was in Japan, I was also taking calligraphy writing lessons from a music mentor of mine named Mika Fujinoki, who’s an amazing percussionist in the underground jazz scene. She’s in a band called Ne and was also the only femme in that space for over a decade. She taught me so much about spaciousness and music. It was a very special experience for me in Japan, so it felt very organic to do calligraphy for this album because it matched the universe we wanted to create. I did a bunch of drafts in New York when we first made the album and then brought it back to her in Japan. She was really great and harsh, just like “I don’t feel the energy in the way you wrote this title. Why don’t you try again?” And then I’d spend like hour-long sessions just writing ‘Planet Q’ over and over; or hand carving a Planet Q hanko stamp from stone. Everything that I treasure about that experience in Japan I wanted to put in the record as a kind of homage to our mentors and the people who supported us while we were there.

On that note, who are some other heroes and mentors that you’d like to shout out?

K: My butoh teachers, Hiroko and Koichi Tamano in Berkeley, California who have of course mentored me physically and taught me so much about movement, but also butoh as a way of life more than anything. Unken san, Tamie-san and the dodoitsu family – who I met the same time I met Tomoki – completely expanded my consciousness around patience, love, vibrations, and the arts.

Lastly, we always love to share as much music as we can with these articles. What albums or artists are you listening to right now?

Tomoki Sanders:

Kyoko Takenaka: