The summer is halfway over and you’ve been scrolling for like, what, six weeks straight now? Step away from your phone (after reading this, of course). An analog […]

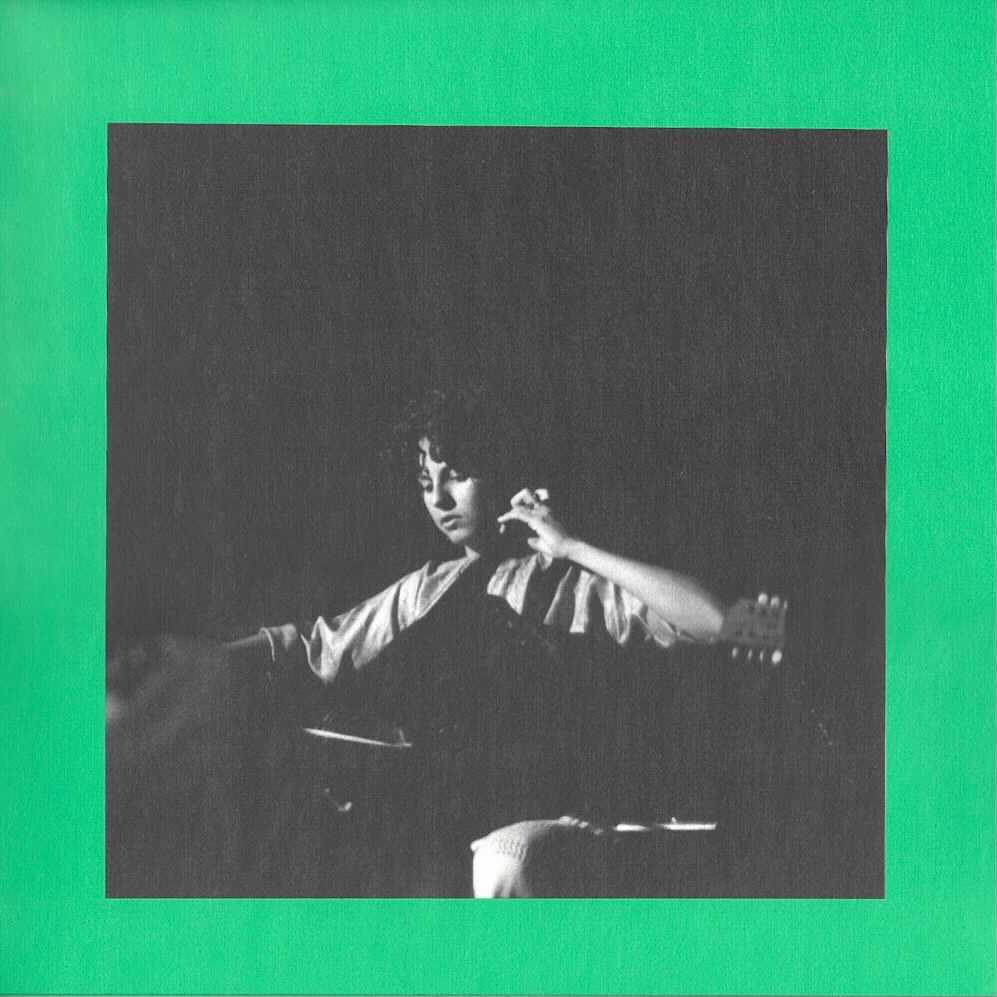

Music is a portal: Priscilla Ermel’s verdant world of sound

Andy Beta interviews Brazilian singer/composer Priscilla Ermel.

“Dear Mr. Eno, I would like you to know about our work, we work with tapes and sounds of Nature.” So read a note tucked inside of Brazilian percussionist Marco Bosco’s 1983 album Metalmadeira, which record collector and reissue producer John Gómez scored in a British thrift shop. It no doubt never reached Brian Eno’s ears, but thanks to the efforts of Gómez, it was finally heard by a wider audience with the release of Outro Tempo. This 2017 compilation (released by Amsterdam label Music from Memory) presented a sound that even the most devoted listener of Brazilain music, be it bossa nova, tropicália, or baile funk, might have been wholly unfamiliar with. Exploring the experimental sounds emanating from Brazil still under the heel of the violent, repressive junta that had ruled the country since the 1960s, each selection was a sonic wormhole.

Heady as the set was, the clear standout came from Priscilla Ermel and her 15-minute epic, “Corpo do Vento.” While Ermel was a singer/composer interested in the music of indigienous peoples, she also used wide-ranging instruments like the viola, ocarina, Chilean chirimia, and Nepalese flute, mixing it all together into something dreamy as ambient music yet also powerfully kinetic in its use of thundering hand drums. Across four albums released with little fanfare between 1986 and 1992, Ermel’s music transcended easy categorization: dashes of folk, classical, ethnographic, and experimental all tangled together. Imagine if—instead of sampling those booming drums on “The Jungle Line”—Joni Mitchell had instead gone to live and study with the Royal Drummers of Burundi, and you have an idea of Ermel’s sound.

Thankfully, Gómez and Music from Memory collected even more of Ermel’s singular music for a recent compilation, Origens Da Luz. Fascinated by her music, we conducted an email interview with Ms. Ermel (helpfully translated by Gómez) during the early months of the pandemic to learn more about her story.

Tell me about an early memory of sound.

I was born in 1957. My childhood memories are very much focused on the sonority of the guitar, which is the first instrument that I played, and that was (and still is) my great companion, my friend and confidant. But also the sounds of the sea, the forest, and the piano which could always be heard at home.

I read that you grew up in a musical family. Was bossa nova important to you?

Yes, I grew up in a musical family. My mother was a piano teacher, and my brother is a self-taught pianist who is in love with traditional jazz. My father died when I was 5, and my mother supported us with these lessons. She plays Chopin wonderfully. I don’t really know how to classify in which social class I was raised. We had very limited economic resources, but my mother and grandparents always valued education and the development of artistic and emotional sensitivity. My grandfather came from Lebanon at the beginning of the last century, and my grandmother is of Portuguese descent. We lived in a working class neighborhood with small factories, in the city of São Paulo. From my bedroom I could hear the traditional samba school Camisa Verde e Branco rehearsing for carnival. The São Paulo samba, as well as the marchinhas and marchas-rancho, gave life to my childhood carnival brincadeiras (jokey games or amusements).

I started playing guitar at the age of 6 and my repertoire was bossa nova, mixed with songs from the jovem guarda and songs from Brazilian popular culture. I really liked Baden Powell, Edu Lobo, Chico Buarque, Tom Jobim, and Geraldo Vandré. We listened to a few records. My brother and I had a portable record player, and I remember listening to João Gilberto’s album, but also Roberto Carlos, the Beatles, and singles from the 60s. But it was the harmonic and melodic richness of bossa nova and the Brazilian songbook, which goes much further with sambas, maxixes, baião, moda de viola [caipira music], ponteados, choros, samba-de-roda …. it came from the daily experience of playing guitar and singing every day.

I did two majors at university: Literature (Portuguese and Spanish) and Social Sciences, then undertaking a master’s degree, doctorate and post-doctorate in Anthropology. However, my musical education is rooted in my self-teaching, and in the learnings I acquired from masters of Brazilian oral traditions—indigenous, caiçaras, caipiras, and other artists with whom I lived together with other free-spirited courses with some wonderful teachers.

What made you want to write your own songs?

I don’t know if it can be described as a want, or if it was a spontaneous need to express myself. I just felt that it was my way of communicating and also understanding the world. My feeling has always been that I was a kind of bridge between different worlds when I composed. It took a long time for me to take on the personality of a composer. I think that composing melodies and writing poetry is something mysterious. There are poems that I wrote and—to this day—I am learning to decipher my life through them.

When did you become aware of the oppression of the military regime?

As a child, it had little effect on my life and that of my family. But when I entered university and became aware of what we were experiencing, I experienced many feelings: sadness for feeling that I was living in a cloistered youth, an intense desire to work to achieve a social balance between rich and poor, and also the perception that many things were being confused behind inflamed speeches and manipulated ideologies. Anyway, I realized that life was much more complex than it was. On the other hand, I have always had an affinity and a strong desire to help people, to understand others, and to act, take care of, transform, and seek harmonies between the different or those who are (or are made to feel) different.

Is there a lot of awareness of indigenous peoples in Brazil in popular society?

The history of Brazil is one of unrestrained colonization in the exploitation of natural resources, which leaves profound marks, in all social strata of our people, even today. Wealth —that is, the value attributed to the exploitation of the land—seems to have entered our culture as being normal, necessary, and really worth doing. So we continue with the mining, with the destruction of rainforests to place cattle and extensive plantations. All follows the old logic of linear, cumulative development, which depletes living beings, creating immense imbalances in the matter that sustains us here on earth.

The latest political developments have shown how fragmented we are as a people. The same tension of conscience about the native peoples that exists here exists throughout the globalized world.

Native peoples lived (and still live) in a different perception of matter, what we would call natural resources. And that is what bothers our society. We must understand that what we call “Brazilian society” is an amalgamation of many different beliefs, values, and cultural heritage. It is a deeply unequal society in different aspects: not only material and economic, but also moral, ideological, artistic, spiritual, and cultural aspects. Thus, thinking about the relationship of Brazilian society in different social strata with native peoples is quite complex. There are people who still consider natives a “backward” people (because they are still alive, and hindering the exploitation of natural resources), even those who also consider them “saviors” of humanity, for their knowledge and traditional ways of life in harmony with the land. The big question remains the greed for natural resources. This greed is the greatest tragedy that we inherited from the Europeans who colonized us, and that the contemporary world (that encompasses us as well) continues to feed us as “valuable.” Native peoples have another conception of time, of land, in relation to the vitality of the place where they live. An organic and sacred relationship that is not understood overnight. To understand them, you have to dedicate time, listen, and desire to know the unknown.

Nowadays, I feel that it is no longer a question of talking or thinking about Brazilian society. The latest political developments have shown how fragmented we are as a people. The same tension of conscience about the native peoples that exists here exists throughout the globalized world.

Your music draws from time spent with these indiginous tribes. How did you encounter the Cinta-Larga and Ikolem Gavião people in the southwestern Amazon forest?

I first met the Cinta-Larga ethnic group in 1981, and later the Ikolen Gavião group. At the time, I was taking a master’s degree in anthropology and lived in São Paulo. However, something told me that life was more than what I saw and lived in that megalopolis. I had a great desire to meet other people. And then my advisor asked if I would like to research the Tupi-Mondé music of the Cinta-Larga. She wanted to decipher a song of theirs, and she thought that only a musician could do that, because it was a very different sound universe from ours. I accepted the challenge and made three trips to the Aripuanã Indigenous Park between 1981-1984, which was already experiencing the disastrous impact of the construction of BR 364 interstate highway financed by the World Bank.

Initially there was difficulty in establishing communication without mastering their language. I developed forms of contact with gestures and music, but their sound universes were so distinct that music proved not to be exactly a universal language as I believed. It took many years to unveil the music of these peoples, and I think there would still be a long way to go. I still do not find a “concept” for Cinta-Larga music, because their sound reality is not even thought of or realized within the parameters of what we call “music” in non-indigenous cultures. What I can share is that the musical sound experience of the Tupi-Mondé peoples permeates many spheres of life: hunting, talking with animals, harvesting honey, healing rituals, singing mythical narratives and playing on the flutes, the emotions of the feelings, everyday loves.

When I say that music is a portal, I speak of a very personal experience, but one I have also had as feedback from others regarding my music. I really feel that I am experiencing and sharing the sensitivity of other peoples when playing instruments that they have created.

Were you working on your first album before visiting the Cinta-Larga Indians? Or did your ideas for the album come after your time with them?

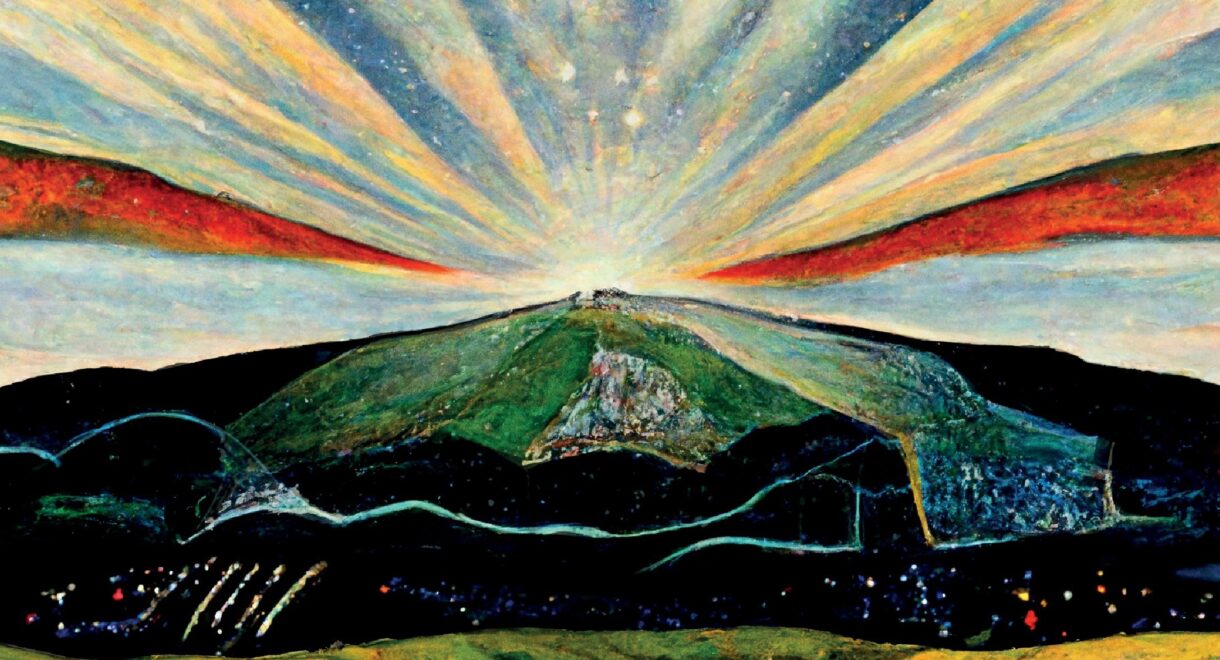

Maybe I can think that all the experiences from that moment in my life flowed together to make my first album, 1986’s Saber Sobre Viver. Some songs had already been written before, but in the village I made several field recordings, because my research was about their music. And I do think that the sound of the forest that is in Saber Sobre Viver and now revives in Origens da Luz can act as a portal for people to penetrate the forest.

When I say that music is a portal, I speak of a very personal experience, but one I have also had as feedback from others regarding my music. I really feel that I am experiencing and sharing the sensitivity of other peoples when playing instruments that they have created. There are melodies, poetic images, timbres, and rhythms that seem to unveil people’s stories, the cultures that gave rise to them. It is difficult to write about it, because it is a transcendent, subjective and very real experience for me. It is very important to be aware that the forest had this sound. I don’t know what it would be today. The music of the forest depends on the life of the forest. One cannot exist without the other. Everyone sings: trees, birds, insects, animals, plants, streams.

Field recordings have become music in my work and in my life, but it is not just any recording but sounds with which I lived intensely in the rainforest. These recordings are full of meanings, life stories, emotions. I have always worked with sounds that I recorded myself, or that came from the hands and ears of Hugo Gama or Roberto Ferraz, who became dear partners in the production of the album Saber Sobre Viver, and everything I did afterwards as well. With them, my music was embraced by the direct sound of cinema in a subtle and deep way. I am a person who listens all the time, and my relationship with the world is primarily auditory. Even when I am composing, I am listening to the life around me. It is not the sound of the environment, because there I am very much like the Indians: me and the place where I am are a single fluidity of life which pulsates together, organically. My time is the time of the earth, of the seasons, of the tides, defined by the place where I am on Earth. Now, when I write to you, I am a tropical winter with its beautiful yellow light filled with birds and insects.