A conversation about her listening habits and life with music ahead of the January 24th performance at the Wallis in Beverly Hills. Arooj Aftab is a Pakistani American […]

Afro-Mingei: How Theaster Gates Sparked Takuro Okada’s Meditations on Influence and Identity

Okada’s latest album channels the spirit of ‘Afro-Mingei,’ bridging Japanese folk craft and Black musical traditions in a meditation on connection, influence, and enduring beauty.

When Takuro Okada began shaping his new album Konoma, he returned to a question that had followed him since childhood: How can a Japanese musician engage with the legacy of African American music without simply echoing it? He found a framework in visual artist Theaster Gates’ concept of Afro-Mingei, which links Black aesthetics and Japan’s folk craft movement through shared ideas of resilience and everyday creation.

“I’ve often reflected on the painful history behind the music that’s nourished me,” Okada says. “There are moments when I pick up my guitar and hear a voice whispering: ‘Should someone Japanese like you really be playing the blues?’ — and I find myself unable to move my fingers.” With Konoma, he says, “that influence is finally brought to the forefront in musical form.”

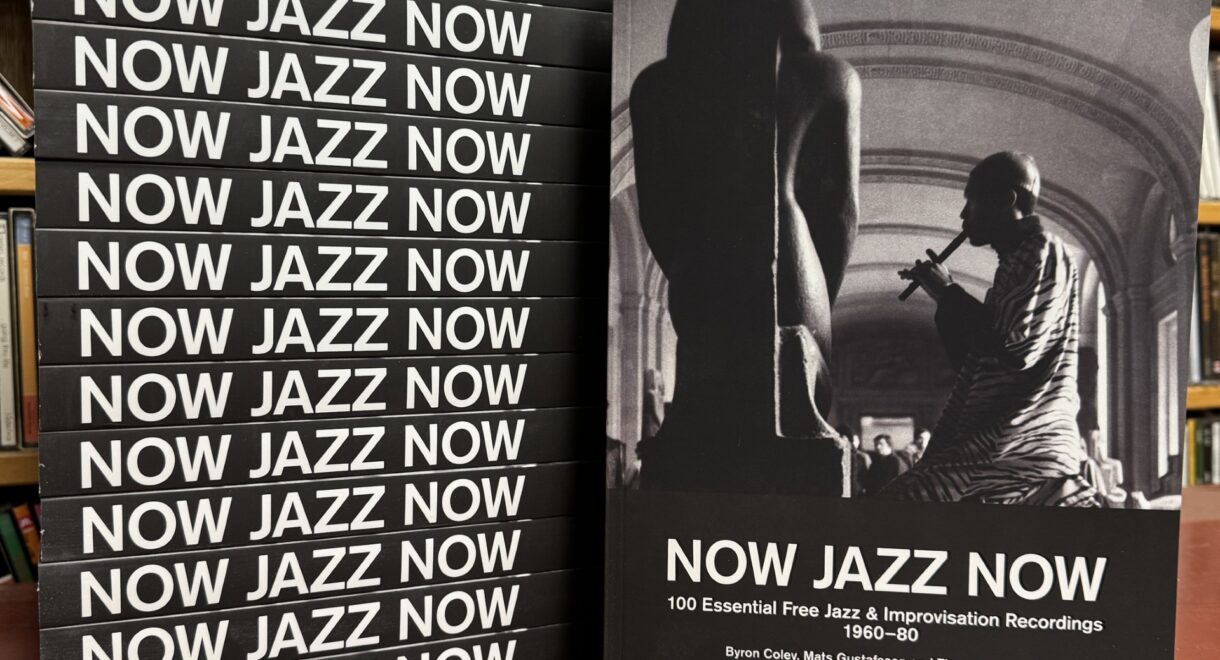

The album, which comes out Friday and is available for purchase at the ISC Shop, enters the world through a partnership with Temporal Drift, the essential Los Angeles-based label known for treating both archival and contemporary work with rare care. Their reissues of Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Surround and Flora, their officially licensed releases tied to Les Rallizes Dénudés, and their work with modern artists like Yuma Abe reflect a philosophy that balances preservation with present-tense creativity. Konoma sits comfortably within that lineage. Join us for a listening party this Friday in the JACCC hidden Japanese garden.

Across six originals and two covers, Okada draws from Sun Ra’s electric meditations with his Arkestra, trip-hop’s late-night pulse, and the patient phrasing of Japanese fusion. Working with a small circle of collaborators to create a huge sound, he lets tone and breathing room define the album’s shape. “Music as true communication — beyond language and cultural background — that’s something truly beautiful,” he says.

Raised in Fussa near the Yokota U.S. Air Force base, Okada grew up playing guitar in clubs for American servicemen before moving into collaborations with Haruomi Hosono, Nels Cline, Sam Gendel, and Carlos Niño. Konoma follows his archival-based release The Near End, The Dark Night, The County Line on Temporal Drift and stands as his most personal statement yet. What follows has been edited for length and clarity. Translation by Yosuke Kitazawa.

The idea of “Afro-Mingei” sits at the center of Konoma. What does that phrase mean to you personally, and how did it start shaping the way you approached this music?

My first musical experience was playing traditional Japanese festival music on the drums for a local festival. I was about six or seven years old. During the summer festival, we’d ride on floats, beating on a drum as we paraded through the streets. Later, around age 11, I started playing guitar and became obsessed with blues and rock, eventually giving up the drums.

During my teens, I suddenly noticed the disconnect between Japan’s pop music charts and its traditional regional music. Meanwhile, in America, I felt there was a seamless continuity between genres like gospel or bluegrass and popular music. This reflects the complex intertwining of national and regional cultural development, and discussing it fully would require more than a book. While I became deeply immersed in the pop, rock, blues, and jazz that captivated me as a child, somewhere in my heart, I felt like I was borrowing from another culture when I played as a Japanese person. Yet American-style pop music was also playing on TV and in the streets where I grew up.

That said, jazz, while rooted in blues and gospel, couldn’t have emerged without Western harmony theory, and blues itself blends earlier cultural elements. The history of Indonesia’s kroncong, often called the world’s first popular music, is also incredibly fascinating. These aren’t just musical crossovers; they’re connections between the spirits and emotions of people born and raised in different cultural spheres and eras.

Just before starting this record, after my first trip to America, I felt anew that I was Japanese. I grew up in a town with a US military base. Yet living in Japan, I rarely interacted with people of different cultural roots, nor reflected on my own. It felt like the first time I had the chance to deeply consider the psychological conflict of being Japanese. Then, as I was revisiting my thoughts about blues and jazz, I happened upon the term “Afro Mingei.”

Were you familiar with Theaster Gates’ work before you saw the Afro-Mingei show in Roppongi, or did you walk into it cold? What was it about that exhibition that stayed with you?

I didn’t know his name until that day. While walking around Roppongi, where I’d gone just to clear my head, I was thinking about the very things I’d mentioned in the previous question when the phrase “Afro-Mingei” suddenly caught my eye. Since I’d been focusing on this topic at that exact moment, I was stunned.

I had absolutely no prior knowledge. His work is highly context-dependent, requiring not just viewing the pieces but deciphering the underlying context. I think that day holds the record for the longest time I’ve ever spent in an art museum. The exhibition carefully annotated the issues of Black Art and the Mingei movement from a contemporary perspective, yet the works still celebrated a sense of beauty and exchange across cultures. In today’s internet-saturated world, the time spent imagining and contemplating context feels like something we’re losing.

“[The exhibition] celebrated a sense of beauty and exchange across cultures. In today’s internet-saturated world, the time spent imagining and contemplating context feels like something we’re losing.”

But the strongest impression came near the exit, in a bar-like Afro-Mingei space with a DJ booth and a neon sign that read “Tokossippi” (Tokoname + Mississippi). It was peaceful and unexpectedly disarming, almost anticlimactic, but it dissolved a tension I’d been carrying. In that moment, I wanted to make something where my interpretation of the blues blended with a distinctly Japanese sensibility.

You’ve written about carrying this quiet question: how a Japanese musician can honor African American music without simply borrowing from it. When did that start to feel like a real creative weight?

As a teenager, I absolutely loved listening to and playing blues. I was the kind of kid who spun Howlin’ Wolf every day, chased Hubert Sumlin’s licks and carried William Melvin Kelly’s short stories in my bag. At the time, I regretted not being born American, and I certainly couldn’t afford to travel there.

Then I discovered Happy End and Haruomi Hosono. They took influences from contemporary American music and made something only Japanese musicians could make. They became a guiding light. Still, I felt a spiritual distance between the cultural background that produced the blues and myself as a Japanese person of the internet generation. Loving the music couldn’t bridge that gap. For years, that kept me from making records that engaged those traditions directly.

Was there a moment during Konoma when you felt like you’d finally made peace with that tension, or at least found your own way through it?

That’s a tough question. In my twenties, I probably saw making music as self-expression, but in my thirties that feeling has faded. Even my tuning and techniques are rooted in insights discovered by musicians before me. Claiming originality feels presumptuous.

But I did feel I could practice a kind of cultural inheritance — something I saw in African American artists like Theaster — through the environment and perspective I grew up with. When touring America, conversations with local musicians and record collectors often turned to Ryo Fukui or Jiro Inagaki when I mentioned being Japanese and loving jazz. They were masters who explored the intersection of Japanese identity and jazz in the post-bop era. Strangely, among musicians of my generation, that era rarely came up, nor did records that carried that spirit.

Within that space, I hoped telling this story through music — about Japanese ideas predating the Meiji Restoration, the struggles after Western culture arrived and the act of looking back at one’s roots to move forward even a little — might connect to my respect for African American music.

Jan Garbarek’s “Nefertiti” and Hiromasa Suzuki’s “Love” are striking cover choices. What drew you to those pieces, and how do they fit into the larger conversation Konoma is having?

I’ve always been fascinated by the period from 1968 to 1972 in both rock and jazz. In jazz, this came after Coltrane’s death, when post-bop and free jazz had reached their limits. Musicians were deciding whether to go further into the avant-garde or embrace crossover ideas. Outside the US, many musicians were actively exploring how to express jazz in their own cultural languages.

“I hoped telling this story through music — about Japanese ideas predating the Meiji Restoration, the struggles after Western culture arrived and the act of looking back at one’s roots to move forward even a little — might connect to my respect for African American music.”

The original recording of “Nefertiti” gathers players who later became ECM stars, and I felt that era’s atmosphere in it. One early idea for the record was imagining what would happen if Ras G mixed using the beat from Hiroshi Suzuki’s recordings.

I first discovered “Love” through an Akira Ishikawa album. That record, Africa, was his way of confronting the drum’s origins. I found an old jazz-magazine interview where he said he long wrestled with his Japanese identity but eventually wondered: “If there’s Afro-Cuban music, couldn’t there be an Afro-Japanese path too?” He traveled to Africa often during that period. His words felt close to the spirit of Afro Mingei, and I sensed an affinity between that exhibition space and this piece of music.

Don Cherry comes up a lot in your notes, not just musically but philosophically. What do you take from him beyond the sound?

I have a favorite story about Don Cherry. A jazz musician once visited him at home, and since instruments were around, they decided to play. The musician asked, “So, what song should we play?” Don looked puzzled — as if he didn’t understand the question. He was always playing. For him, music was as natural as breathing or talking to the person right in front of him. That story symbolizes how deeply music was woven into his life.

You worked with an incredible group of players on this album, including Shun Ishiwaka, Kei Matsumaru and Marty Holoubek. How did those sessions unfold? Were you guiding things closely, or letting the players stretch?

No one on this record played together at the same time. It may sound like a jam ensemble, but I recorded everyone separately to achieve a different temperature than a jam. I also wanted the mood of sampled beat music in the mix: minimal repetition and shifting heat. I was testing whether distant approaches could run parallel.

They’re exceptional players, like wild animals that never miss the slightest movement. To gauge their reactions, I sometimes triggered dub-like interventions from the control room while they were recording. For some tracks, I cut the tape into pieces, tossed them into the air and reassembled them.

When producing Konoma, how much of it was planned and how much discovered in the studio?

Both. With Betsu No Jikan, I improvised and edited without knowing what the music would become. This time, I wanted more concrete forms. So each element — improvisation, editing, structure — ended up being used in roughly equal measure.

The album moves between improvisation and precise editing. How do you decide when to let a performance breathe versus when to sculpt it?

I wanted the boundaries between those approaches to blur. Improvisation was sometimes planned, and editing was sometimes spontaneous. I did extremely precise edits—threading-a-needle level—but always with the goal of creating a raw, loose mood. Sometimes I even returned to the original take after heavy editing. Even if the sound felt similar, the process itself mattered for this record.

The story about Ethio-jazz and enka is fascinating — these accidental crossings between cultures. Do you think moments like that still happen in today’s hyperconnected world?

Hard to say. Before the internet, misunderstandings and subjective interpretations created openings for accidental cultural exchange. Those big, unpredictable crossings feel harder now, but I still think they can happen. Japan and America still have different cultural landscapes, and people’s lives and perspectives differ in ways that make such exchanges possible.

As for the liner-notes story, I heard it from an engineer, so the truth isn’t clear. I researched it but couldn’t find solid documentation. But I did find an old music-magazine note saying, “I’ve heard the theory that Ethiopian soldiers stopped in Japan on their way home from the Korean War and brought back enka records.” So it seems the rumor has circulated for a long time.

Earlier this year you released The Near End, The Dark Night, The County Line. Did revisiting your older work shape how you approached Konoma?

It’s like rowing a boat while facing backward—moving forward while looking behind.