The summer is halfway over and you’ve been scrolling for like, what, six weeks straight now? Step away from your phone (after reading this, of course). An analog […]

Labels We Love: Temporal Drift (Los Angeles)

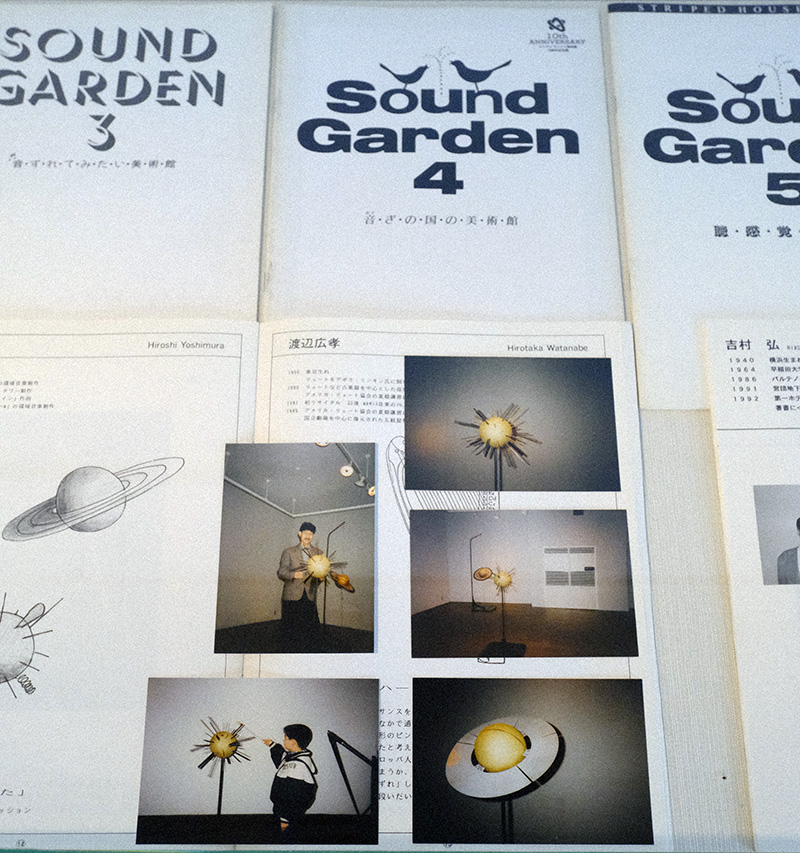

A look into the young label behind the first-ever official reissues of Les Rallizes Dénudés and Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Surround.

Temporal Drift is an independent record label launched by two veterans of the reissue game, Yosuke Kitazawa and Patrick McCarthy, who over the last 10+ years have made an indelible mark on the industry through their work on seminal reissue projects like I Am The Center (Private Issue New Age Music In America, 1950-1990), Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980-1990, Pacific Breeze: Japanese City Pop, AOR And Boogie 1976-1986, Country Funk 1969-1975, Rodriguez – Searching For Sugar Man, Lifetones – For A Reason, and countless others that you’ve probably heard, own, and love.

The new label builds upon McCarthy’s years of production expertise along with Kitazawa’s deep connections to Japanese artists, musicians, and labels made through his numerous trips and long meetings in Japan over the years, which, in many ways, opened the door for the recent Japanese reissue boom. The label’s releases include protege of Haruomi Hosono Yuma Abe’s debut solo album Fantasia, cult experimental noise band Les Rallizes Dénudés’ first-ever official reissues, and an “environmental music” masterpiece from ambient legend Hiroshi Yoshimura. Beyond just the impressive lineup, the label approaches each release with an immense focus on quality and detail. Case in point, Temporal Drift’s Surround reissue includes an accurate reproduction of the vellum plastic inserts that were featured in the original CD release of the album.

Below, In Sheep’s Clothing’s Phil Cho spoke to Temporal Drift’s Yosuke and Patrick to learn more about the label’s beginnings, working on Les Rallizes Dénudés and Hiroshi Yoshimura releases, vinyl production, upcoming projects, and more!

How did the label first get started? Where does the name Temporal Drift come from?

Yosuke: The label started about three years ago now. Patrick and I both used to work at Light in the Attic Records as producers and project managers. We did a lot of stuff there, production, licensing, and all that. Around the time the pandemic started, I was let go from Light In the Attic, and Patrick was let go a little bit earlier. I think we both felt that we had some unfinished business. Like with Hiroshi Yoshimura, there was still a lot more material that should be reissued. Patrick and I were chatting about how we could make that happen. Patrick suggested that I form a label, and then we just decided to do it together.

Patrick: I worked on over 500 projects at Light in the Attic, and I co-produced or produced maybe 100 of those. Yosuke did a whole bunch, too, and we did things together. We had everything we needed and knew how to do all this stuff. We just needed to figure out what it was. In terms of the name, I remember we didn’t want “records” in it. We wanted it to be a name that was a little bit more obscure. We talked about architectural terms, photography terms, and all these different things. One day I woke up in the middle of the night and said “change temporal.” We talked about that and thought “temporal” was interesting. What’s the meaning of temporal? It can be relating to a specific time, finite time, and earthly time, or it can also be a chronological series of events. Then the “Drift” idea came to me because, personally, I love listening to music on headphones. I feel like I just get into it so much more. When I’m really into listening to a record on headphones, I feel like drifting off and losing myself in it. For me, that’s what I hoped the label would do – give people a space like that to go inward and lose themselves in the sounds.

Did you have an underlying ethos or mission behind the label when you first started?

Y: I think we knew that we wanted to do both reissues and contemporary music. In terms of sound, it’s basically whatever we like. The first idea that we had was Hiroshi Yoshimura, and then we started talking about Les Rallizes Dénudés. I remember discussing if we wanted to do something that’s so much more rock and noisier? I think in the end, it makes sense to have both Les Rallizes and Hiroshi Yoshimura. It’s like opposite ends of the spectrum, but it makes sense in a way. Noise music can also be ambient. Guitar music, like shoegaze, can be considered a form of ambient music. With Yuma Abe, his Fantasia album actually ended up being the first release on our label. I think that worked out really well, too, because his music touches on all the music, like Hosono and the folk rock type stuff that we like. Also that album, in particular, he was influenced by stuff like Mort Garson’s Plantasia and Kankyō Ongaku “environmental music,” so it just all made sense.

P: I think we both have really diverse tastes. There’s music that we both deeply love that probably has no commercial value. You have to be mindful about what you can actually sell on your label, but I think we just really go with our guts and say, “We like this.” Whenever I was producing things at Light in the Attic, it had to have that immediate connection because the amount of time you’re going to work on a project could be years. If you don’t love it, why would you do it? Why would you spend three years working on something and go through all of the turmoil of licensing, issues with manufacturing and costs, all these things you’ve got to deal with, if you didn’t like it. You have to actually love the music in order to dedicate that time because the music deserves it. The work that we put into it, we do that because we respect the work and we want it to be presented in the best way possible.

Patrick, you now work at A to Z Media. With that experience along with LITA, sound quality and production seems to be a heavy focus with the label. Can you talk about that side of the label operation?

Patrick: For years, I was the production manager at Light in the Attic so I worked on everything from getting the audio approved to finding master tapes to figuring out the packaging, finding vendors, trying different pressing plants, etc. I’ve pressed records directly with a dozen plants over the years. In my current day job at A to Z, I work in vinyl manufacturing and have a lot of visibility on print and packaging. I see all these great things that other labels do. I have a really wide view of what the landscape is. Having all of that expertise and real-world experience, I bring that to our label and can say, “Oh, this type of jacket would be really unique… We could emboss it or add a heavier weight to the jacket… Try this pressing plant, this cutting engineer, or this plating facility.” Especially with Hiroshi Yoshimura, I think we first cut reference acetates to make sure the music would even sound good on vinyl, tried two different pressing plants, we cut lacquer, we tried different plating options, multiple rounds of test pressings at different plants. All of that stuff.

It has to be as good as it can be because nothing is perfect in physical music format media. You’re always going to have variances. But I know what those guardrails are, and I know what the acceptable tolerance ranges are. So I can take that knowledge and say, “Well, we need to try this, or we have to do test sheets of the print of the jackets to make sure the color shift isn’t too far.” For Hiroshi Yoshimura, we wanted to reproduce the vellum plastic inserts that were in the original, and those have been extremely difficult to manufacture. Right now, we’re three months into waiting for the stock to become available at our third vendor. That’s hard. It might come to a point where we can’t make those anymore. That’s a reality. Having a lot of that day-to-day knowledge definitely helps the label. We run most of our work through A to Z, so have some visibility and control over that side of things as well. It’s interesting. I review product samples and new product offerings. There’s just so much innovation right now in packaging. Labels are doing so many cool things with different types of stocks. More than just color vinyl, I think there are a lot of cool things you can do in box sets. It’s an exciting time for that.

Yosuke, you worked on many of the Japanese projects for LITA. Can you talk about some of those experiences and what you’ve learned about reissuing music from Japan, working with Japanese labels, artists, etc. ?

Y: When I first started working on Japanese releases with Light in the Attic almost 10 years ago, there weren’t too many reissues of Japanese music. Not just reissues, but Japanese music, most of it didn’t really come over here or wasn’t released outside of Japan. I think all the work that we put into doing those Japanese reissues definitely opened the door for a lot of other people to be able to license stuff from Japanese labels and artists. It became more of a common thing, and I think it opened up the idea of licensing from Japan. At that time, it felt like it was impossible because all these Japanese labels are so insular, and they don’t really try to market their stuff outside of Japan. But now it feels like it’s a whole different story. The labels now know that there’s a market for that music here and in Europe and all around the world outside of Japan. There was a point when it got a little bit easier for smaller independent labels like us to be able to license stuff from Japan.

But now that the Japanese labels think they can do it all themselves, it’s getting a little bit harder to license stuff again because It’s like, “Oh, if there’s interest in this stuff, maybe we should do it ourselves, and maybe we can make more money.” But yeah, I feel like now there’s a flood of Japanese reissues coming out and so many reissue labels. I think it’s a good thing. But I always look at the price of these imports and that’s what bugs me; just how expensive they get when they’re imported over here. When a small label like us can put it out here and get the records manufactured for the overseas market, I think that’s a big plus.

“I think all the work that we put into doing those Japanese reissues definitely opened the door for a lot of other people to be able to license stuff from Japanese labels and artists.”

Yosuke Kitazawa

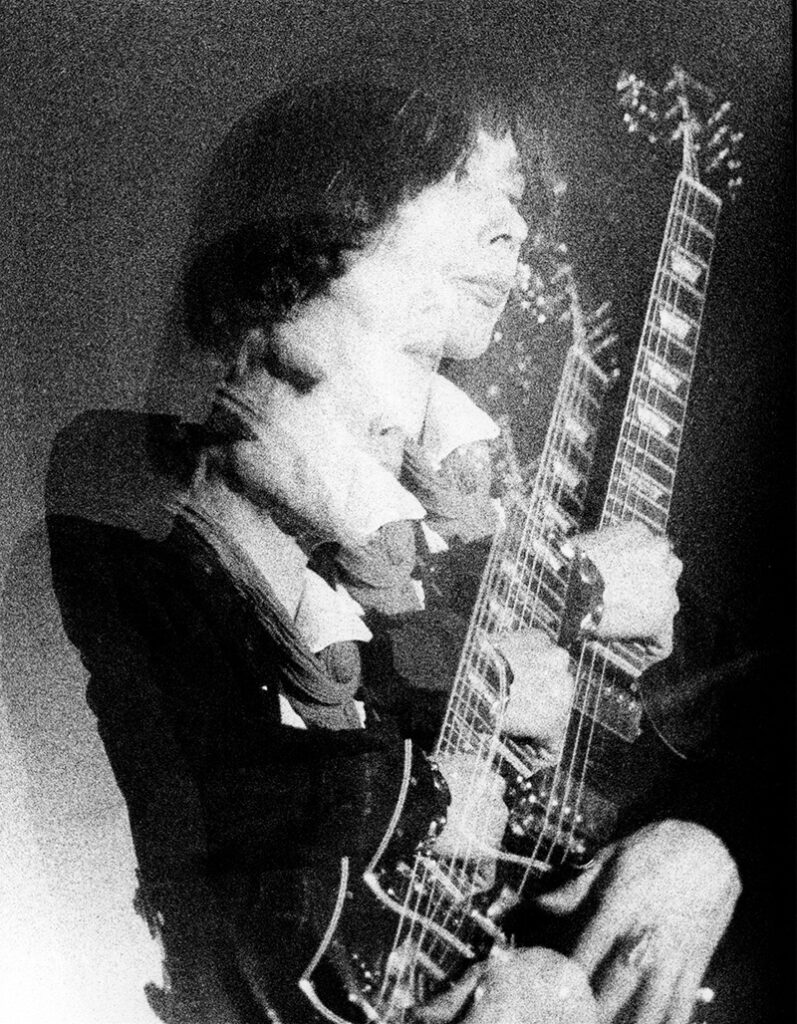

The Les Rallizes Dénudés story is something of a legend or myth at this point. How did the project first come together?

Y: That whole project came about from relationships that I had already built, mainly with Makoto Kubota, who was basically my point person for all the Les Rallizes Dénudés stuff. I did an interview with him for Aquarium Drunkard. I was talking to him about his own stuff because Makoto’s a musician; he has his own bands, like the Sunset Gang, and a lot of collaborations with Hosono. During that conversation, I asked him about LRDN because I knew that he was briefly a member of the band. That’s when he mentioned that there were plans to do official reissues of that material. From that conversation, I just kept up the relationship with Makoto and kept asking him. That’s how it started, and that’s how we were able to do those projects. Makoto knew the work that both Patrick and I did at Light in the Attic, like the Hosono releases and Sachiko Kanenobu, and he was really impressed with that. I think that’s why he trusted us even though at the time we didn’t have any releases yet, but we knew that we were starting up a label.

P: The initial idea was just to reissue OZ Days, this 2LP that came out in 1973. The rights holder, who was the original manager of the venue, had the master tapes. When they got those transferred they said, “Oh, well, there’s all this other material that was recorded that no one’s ever heard.” That’s when we discovered the OZ Tapes material came out of those sessions because only four tracks were originally on OZ Days Live. Then we had so much material where OZ Days Live could be an oral history, like Please Kill Me or releases like that, where you talk about a venue through all these great photos and music that no one’s heard before. Then that started the conversation with the Rallizes estate. It turns out they had all this material in the vaults and were already thinking about doing those things. It was just great. We were in the right place at the right time. We had the experience, and we had their trust in a way from seeing our previous work.

How has the response been with Les Rallizes Dénudés fans?

P: When we started working on those, it was a real unknown because everything was a bootleg before. You had no idea what the sales numbers were like and what the fan base was like. We could tell there were fans out there, but no one had any idea how wide the fan base reached and the types of people. There are so many young teenagers that are huge fans. A lot of young women are big fans of the band.

Y: It’s interesting because in Japan, fans of the Rallizes are mostly older men. Here, it seems like there are way more younger people who are getting into it. It’s a bit different, and I think that’s great. We knew that they were a big cult band, but then to actually put it out and to see the response; it feels bigger than we thought it would be. There was a lot of interest from the media, like NPR, New York Times, and all that. I think the story is really interesting, even though people tend to focus too much on the original bass player running away to North Korea. To the band, that was just a blip in the story of the band. That was just some small thing that happened. People like to focus on dramatic stories like that. I think that helped with the amount of interest around the reissues that we did.

P: I remember we just emailed a bunch of people about the release, did a social post, and the next morning it was on Pitchfork, “First Official Single from Les Rallizes Dénudés.” Then there was a distro mailer that went out, and from that email, a writer for the New York Times replied and was like, “I’d like to do a piece on this.” That turned into a month’s long huge story where he interviewed everyone and interviewed us. He really wanted to tell the whole story. In the middle of all that, The Empty Bottle in Chicago reached out and said they’d like to do a tribute show. I was like, “Wow, there’s a lot of people all over the place that are big fans of this, and they want to participate in it.” I feel like they’re one of those bands that you could have a Les Rallizes convention or something like that where everyone would get together and share their love for the band and their stories. It’s a super tight family. People comment on Instagram all the time saying things like, “Oh it sounds like the bass fuzz from this bootleg…”

Y: It’s like the Grateful Dead in a way where fans just share the tapes that they had of some particular concert. When they actually meet up face to face, it’s just like a whole different experience. There are also fans who don’t like the fact that these are now officially released. They like the underground aspect of the band.

P: Working in archival, that’s something that I’ve always had a very opposite opinion of. It’s not about having a $5,000 record that stays in your basement and you get to brag about it online. That’s not music. It’s about sharing. It’s about accessibility. I can’t buy a $4,000 record, but you can make a good quality reissue that’s actually probably going to sound better than the original, and it’s going to be accessible. You can find it in every record store.

I’ve always been a real hater on people that have that opinion because this music, it’s not a $5,000 record that stays in your collection at four people here and it’s in your basement and no one ever, and you get to brag about online. That’s not music. That’s not what it’s about. It’s about sharing. It’s about accessibility. I can’t buy a $4,000 record, but you can make a good quality reissue that is actually probably going to sound better than the original; it’s going to be accessible; you can find it in every record store; the artist is getting paid for the first time. I think that’s really important. Everyone has their journey. Everyone finds music for the first time somewhere. With Rallizes, the response has been so overwhelming and continues to be.

Mizutani was a pretty mysterious figure and it seems these releases are finally starting to uncover a bit of truth behind him. What did you discuss with Makoto and the estate in terms of how the music should be presented?

Y: I think we always want to make sure that records are presented in the way that the artist or the estate wants them to be presented. Collaboration with the estate is very important; making sure that we’re not doing anything that they don’t like. Sometimes that gets to be a lot of work, going back and forth, having to get approval for every single thing, even social media posts, but I think that’s a really important thing to do and keep up with. That goes with both Les Rallizes, Hiroshi Yoshimura, and with contemporary artists, too. We have to make sure that we’re doing what the artist wants us to do. With Mizutani and Hiroshi, the artists themselves are no longer with us. In working with the estate, family, and other band members, we just need to figure out what the artist would have wanted. What would Hiroshi have done with this reissue? What would Mizutani think of this? Sometimes there are things that you can’t really figure out or do things in the way that maybe Mizutani had wanted. But I think we just try to do as much as we can.

P: Especially in the case of Les Rallizes and Hiroshi Yoshimura, we are working closely with the people that worked directly with the artists. The people that are a part of The Last One Musique are people that were around, for the most part, all of Les Rallizes career, and were in the band or participated in the Rivista projects, that band’s only official album releases. The people working on the design side are people who worked on those albums. So we know that the design is probably what Mizutani would have wanted. It’s the same with the Hiroshi release. We’ve worked closely with those estates on other projects we did at Light in the Attic, so we know how important it is for them to have high-quality and really well produced projects. That involves a lot of back and forth and making sure they’re happy with it.

Also, there are definitely times where we think something is more appropriate to do now than it was in 1986. There are things that you have to do now that are different from what you did 40 years ago. Sometimes we have to bring those opinions to the table and say, “Look, this is not going to happen, but this is what we can do now, and this is what I think we should try to do now,” and have those conversations around it. The experience working on all these projects has been extremely positive. When we were in Japan last year, we had dinners with people and lots of meetings and time spent together. I think it’s pretty clear that they’re very happy with the work we’ve done. It’s really important that they’re happy because obviously, these things wouldn’t happen without their approval. Hopefully that means we’ll just continue to have that relationship progress.

Y: I think with reissues, in particular, you have to find the right balance between trying to recreate it exactly the way it was originally released and updating it to current times. Sometimes we run into trouble trying to make it exactly the same. Like with the vellum insert that was in the original release of Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Surround. We wanted to recreate that, and it was a lot of work trying to recreate it, but in that case, it was definitely worth recreating what was in the original release.

“It’s not about having a $5,000 record that stays in your basement and you get to brag about it online. That’s not music. It’s about sharing. It’s about accessibility.”

Patrick McCarthy

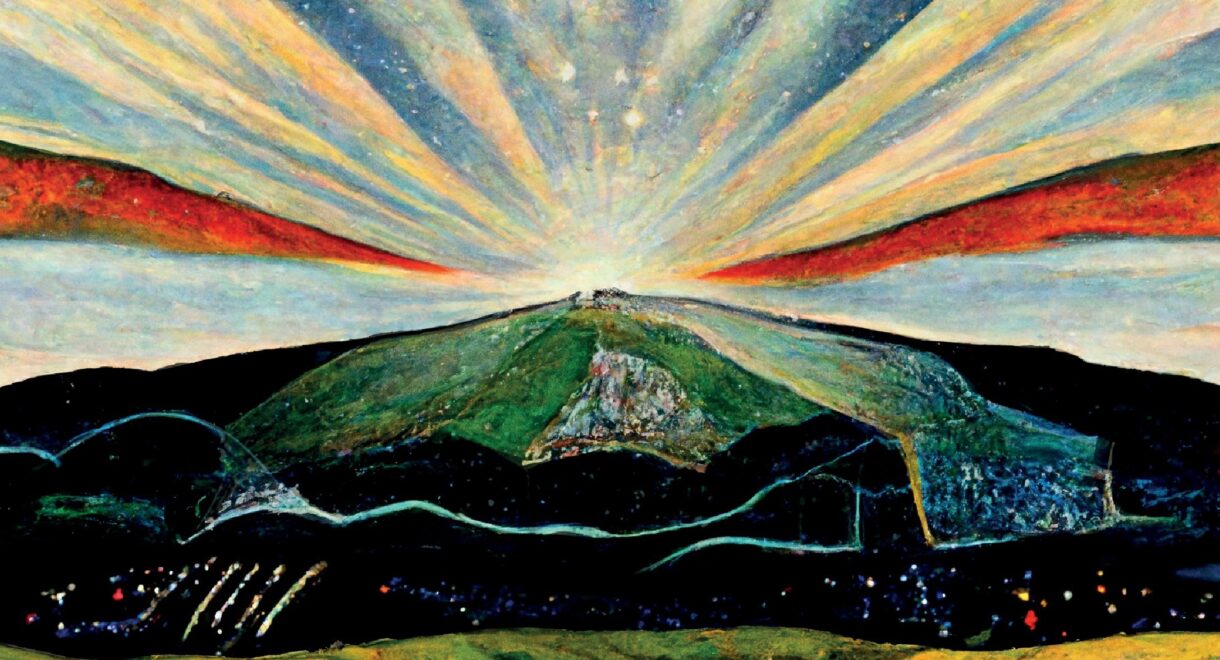

Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Surround is a classic… Can you both share your first time listening to that record?

Y: The first time I heard it was probably through headphones, and I still enjoy listening to it through headphones. On the original liner notes that Hiroshi wrote, he mentioned that it should be listened to with all the background noise; the clinking of the teacups; the hum of the air conditioner, and all that. After I read that, I actually did that, and it works. It’s like part of the environmental noise. He also recommends having it playing while you’re doing stuff. I think that’s a cool way to listen to it. Listening to it closely with headphones works too, because then you notice all these little things that you wouldn’t notice when it’s being played as environmental music. One person told us that they play this music to wake up and get the day going, but then we’ve also heard from other people who say they play this music when they want to fall asleep. It goes both ways, and it works both ways. I think that’s what’s really interesting about Hiroshi’s music. Every person has a different reaction to it, and everyone has their favorite Hiroshi album, and different reasons for liking it.

P: Like Yosuke said, you can listen to it while you’re making breakfast, having dinner, or while you’re working and the phone’s ringing. It’s just a part of the everyday sounds of your environment. I’m partial to having the AC off and getting into the sound because the sounds are just so beautiful in the way they interact and flow. There’s such a simple palette of sounds, but there’s expression in it with the type of melodies and the way they rise and fall. It’s masterful music. Personally, I first heard Surround back when we started working on Music for Nine Postcards. That was my first introduction to the music of Hiroshi Yoshimura. I’d say the majority of times I’ve listened to it on headphones because I’ve been doing predominantly critical listening to try to find pops and tape noise. When you cut reference lacquer, you’re listening to how certain frequencies respond on a turntable, especially with some of this music where you have digital piano and stabbing keyboard sounds. Sometimes in lacquers, you can hear pre-echo, where you hear frequencies slightly before they sound. I spent a lot of time listening for stuff like that. How does the sound change over the course of the record compared to the original?

Any interesting or unexpected things that you’ve learned about him during this whole process?

Y: Last summer when Patrick and I went to Japan, we went to an exhibition of Hiroshi’s works that included both music and also the visual work that he did. That was really eye-opening to me seeing how much of a multifaceted artist he was. He wasn’t just a musician. His creative mind could go anywhere. That part of Hiroshi’s life as a visual artist is something I don’t think too many people know about.

P: For me, that exhibit was truly mind-opening. I knew about some of his visual work from working on these projects, but seeing all the sound sculptures and his video work first hand was something else. His art is so playful, but it’s also very deep. He didn’t seem to take himself too seriously, but he took his work very seriously. That was really evident in the selection of work that was presented. He cared about people’s experience of sound in the world, as evident in his public environmental sound works for tube stations, museums, cafés, etc. He once said in an interview that your stroll to the train station or to the park should be complemented by sounds. There are natural sounds, but then there are also sounds that are created to complement and contrast that space. Some of his subway sounds have this invigorating positivity. It’s so cool.

His video works are very meditative.There were five or six old CRT-type screens with these really zoomed in videos of water. It had such a focused quality to it. It’s clear that he spent a lot of time deeply thinking about his palette, whether that was in his sculptures, video work, or scores. His physical scores are also beautiful with the way they turn into birds and clouds. One of the craziest things I learned was that he was commissioned to write music for the Los Angeles transit system. There was a conversation with him about doing that. He came out to LA, but it would have required him living here for a while, and I don’t think he was able to do that. What a different story he would have had if that had happened. He would have been so much more known here, and it could have opened up his work beyond Japan. In Japan, so much of his public work is still in use. You can still go to the subway station and hear Music for Nine Postcards.

Y: One cool thing I found out through the exhibition is that he really liked drinking beer. He kept all these empty beer cans, and then made instruments out of them. They had a display of all the instruments that he had made from empty beer cans, like kalimbas. Some of his early sound sculptures were made from beer cans. He’s such a fascinating person the more you learn about him. He had a lot of respect from people outside of Japan, even in the ’80s, when he was doing some of his most pinnacle work. It found more people, but it just took a long time. We’re trying to bring over that exhibit they had in Japan, but I think it’s going to be a while before that can happen. There’s definitely a lot of interest. I’ve talked to people that have flown to Japan from America, Ireland, and other places in Europe just to go to that exhibit.

Temporal Drift launched in 2021. What’s coming up next for the label?

Y: We continue to work on Les Rallizes and Yoshimura stuff. This year, we’re really working on putting out more contemporary artists and just more releases. We worked on a bunch of compilations at Light in the Attic, and I think that could be cool because it can be something more unique that you made as a label. We’re looking into that.

P: It was kind of a rapid fire for the first three years. Things have slowed down a bit in the sense that the archives are being dug into and explored. There are things on the horizon that we’re working on. We’re finally about to ship the first official translations of Mizutani’s lyrics that were published in Japan. It’s a super beautiful deluxe box with lyrics in English, Japanese, and French, and some great photos. We want to do some other events; some Les Rallizes events; maybe a show with some of Takehiko Nakafuji’s photos that were exhibited in Chicago last year. As Yosuke mentioned, there’s some contemporary stuff. It takes a lot of time to do these things. I wish they could happen faster, but it takes as long as it needs to take. There’s really no rush in that way. I think the fans are always going to be there.