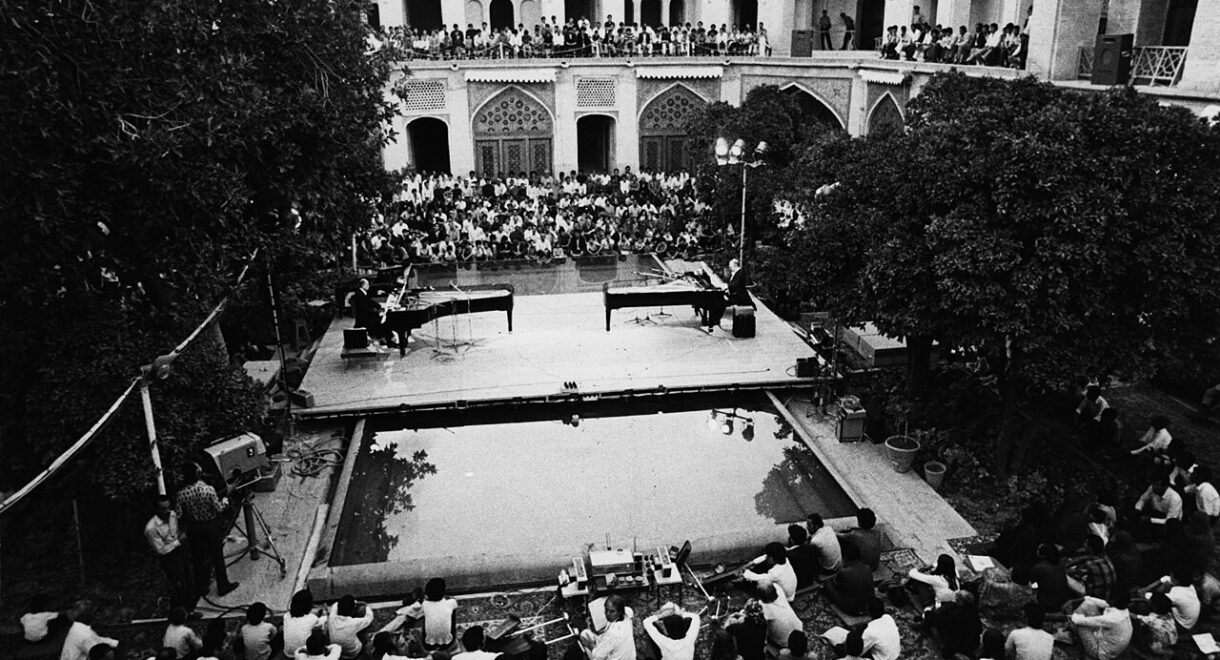

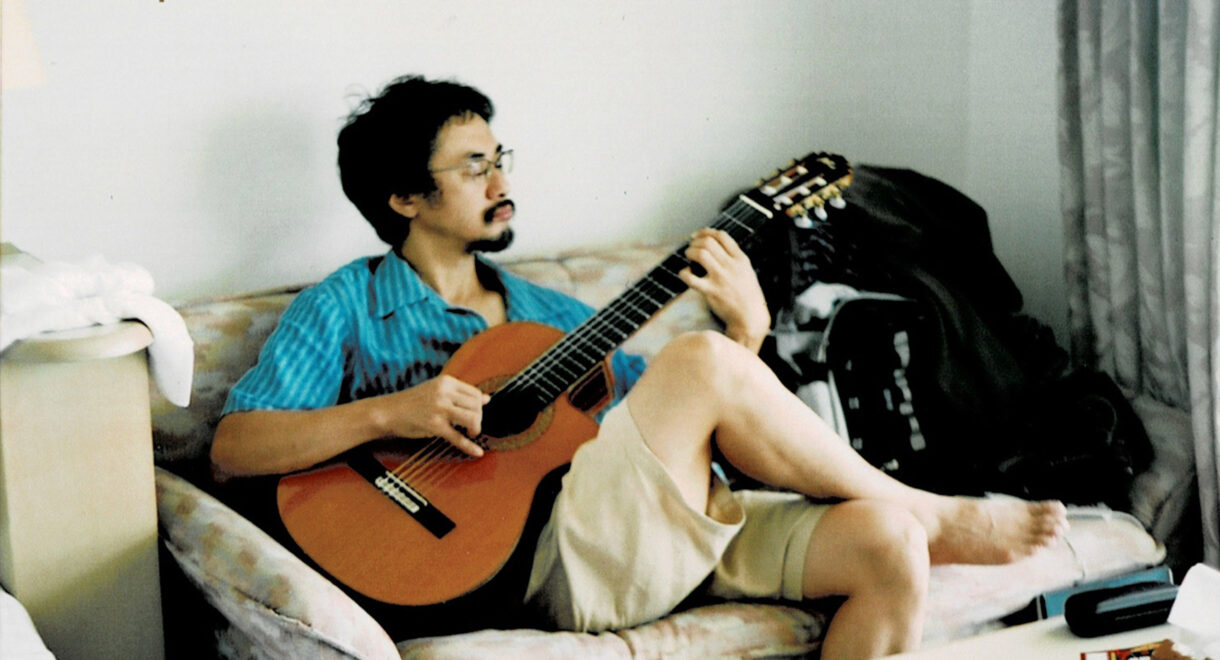

Anthology Of Persian Experimental Music is now available on Bandcamp as a pay-what-you-want download. When Italian curator Raffaele Pezzella began researching experimental music scenes for his label Unexplained Sounds Group, […]

The KLF’s Lost White Room Film: Desert Road Trips, Ice Cream Vans and Rave Mythology

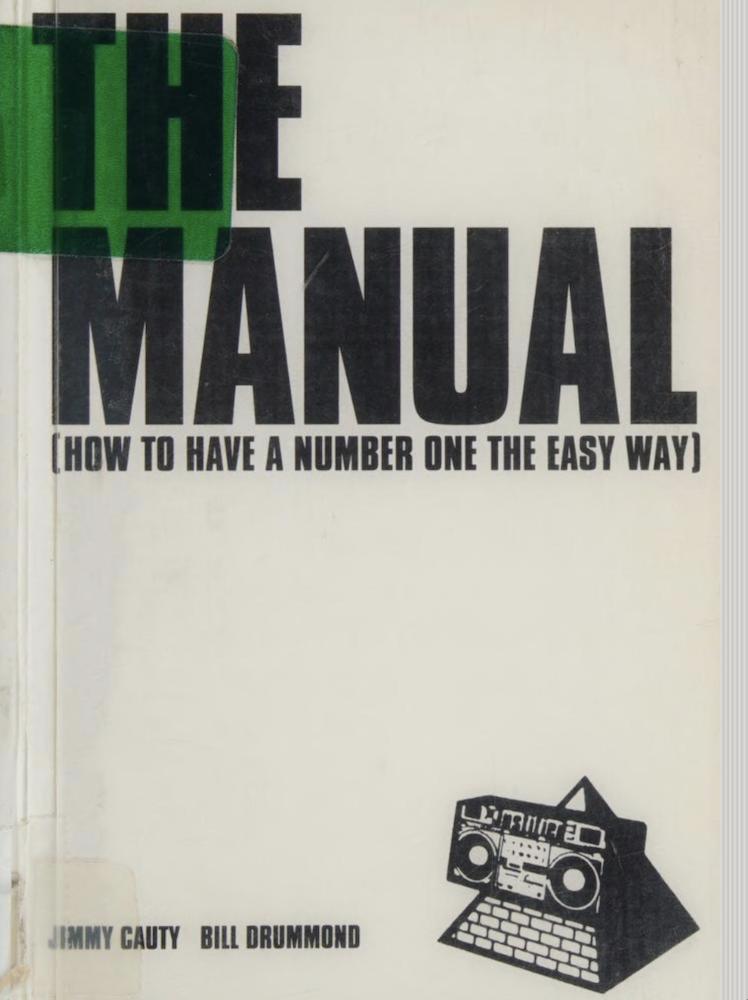

By the time The KLF released The White Room in 1991, they had already proven two things. First, that the charts were a system to be gamed. In 1988, as The Timelords, they published The Manual (How to Have a Number One the Easy Way), a straight-faced blueprint that promised to “reveal their Zenarchistic method used in making the unthinkable happen, a day-by-day, step-by-step guide for anyone who wants to have a number-one single in the official UK charts — no previous musical experience necessary,” as the back cover copy put it. They followed it with “Doctorin’ the Tardis,” which promptly went to No. 1. It read like satire and functioned like proof.

Second, they’d shown they could abandon pop structure entirely. Their 1990 album Chill Out unfolded as a single, continuous nocturnal drift, built almost entirely from unlicensed samples, radio fragments, and found sound. Precisely because of those uncleared samples, it has long remained unavailable on major streaming services, existing in a semi-legal haze that only reinforces its mystique. In fact, we’re not even able to embed it. Here’s a link to it.

That record became foundational for chill-out culture, even as Drummond and Cauty were preparing to swing back toward something engineered for maximum impact. The White Room would pull from both instincts, the mystic sprawl and the calculated hit.

A film came first. Flush with cash and momentum, they decided to bankroll a movie before the album fully took shape. Drummond later recalled the pivot: “Driving down the Marylebone Road, thinking what we were going to do with all this money… we knew we wanted to make a film anyway. We thought if we don’t make a film now, we’ll never make a film. So we started, we made a film called The White Room… and we haven’t finished it yet.”

That impulse produced a surreal, roughly 50-minute road movie shot in Spain. The grand cinematic statement stalled, but the title and much of the ambition survived. What couldn’t be resolved on screen was rebuilt as a pop record engineered to hit with precision. Below is the film itself, the artifact that set the chain reaction in motion.