In conversation with Small Medium Large, a new quintet from the burgeoning new West Coast jazz & improvised music scene. In 2018, LA-based jazz and post-rock guitarist Jeff […]

Triángulos De Luz Y Espacios De Sombra: In Conversation w/ Antonio Zepeda, Eblen Macari and Rolando Chía

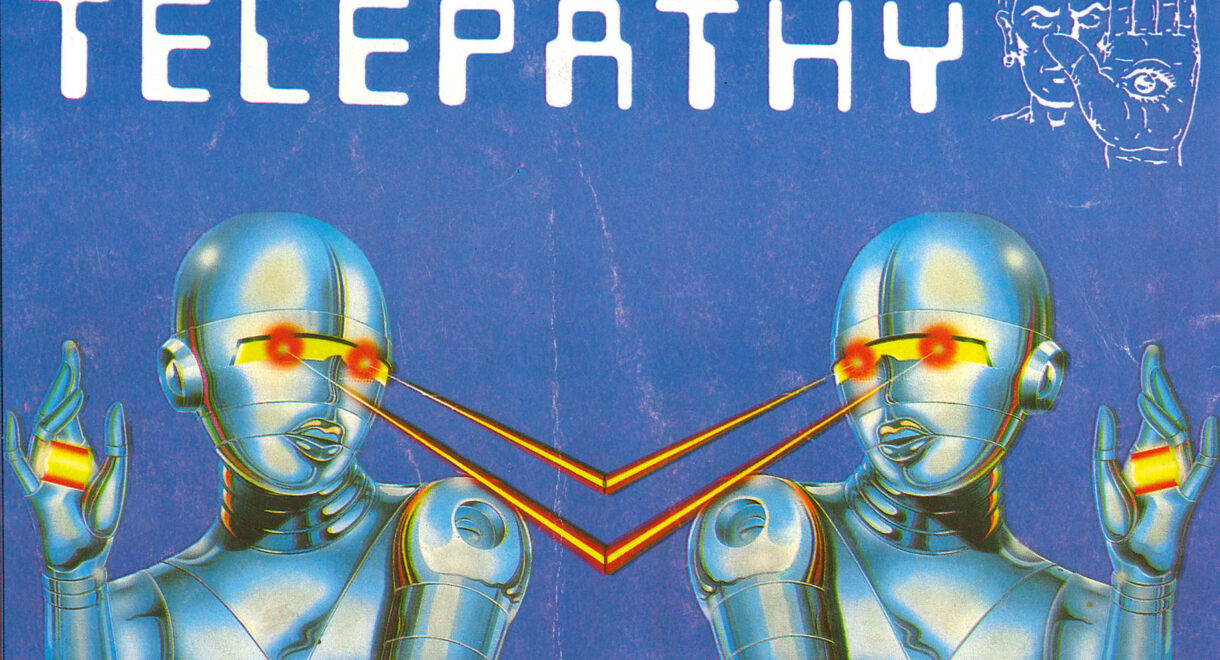

Pre-Hispanic instruments meet synthesizers, drum machines, jazz, and progressive rock on Séance Centre & Smiling C’s latest cosmic meeting.

Earlier this week, in perfect alignment with the solar eclipse, Séance Centre & Smiling C released Triángulos De Luz Y Espacios De Sombra (Triangles of Light and Spaces of Shadow), a collection of visionary Mexican electronic music sourced from obscure cassettes, CDs, private pressings, and personal archives. Tracing a line through time, the compilation deftly recalls the “Concierto del Eclipse” that occurred in 1991 when Mexico City was in the path of the totality. Featuring many of the same artists, like Armando Velasco and Rolando Chía, both the compilation and concert cast a light on a vibrant community of underground musicians “who created a unique speculative cosmology, forging Mesoamerican mythologies with innovative sonic technologies.”

Many of the tracks collected on the compilation, including Armando Velasco’s “Dafne” and Eblen Macari’s “Clarion,” even have a cosmic sound quality about them with traditional instruments alongside synthesizers collectively building expansive sonic textures through reverbs that seem to reflect the vastness of the cosmos. “The synthesizer era inspired a bunch of artists to blend synthesizers with pre-Hispanic elements,” recalls Macari. “Picture this: playing at ancient Mexican archaeological sites. And the cherry on top? A mind-blowing concert during a total solar eclipse in Tula, Hidalgo, back in ’91.”

Available now: https://insheepsclothinghifi.com/product/various-triangulos-de-luz-y-espacios-de-sombra-2lp/

Release notes capture the spirit of the endeavor:

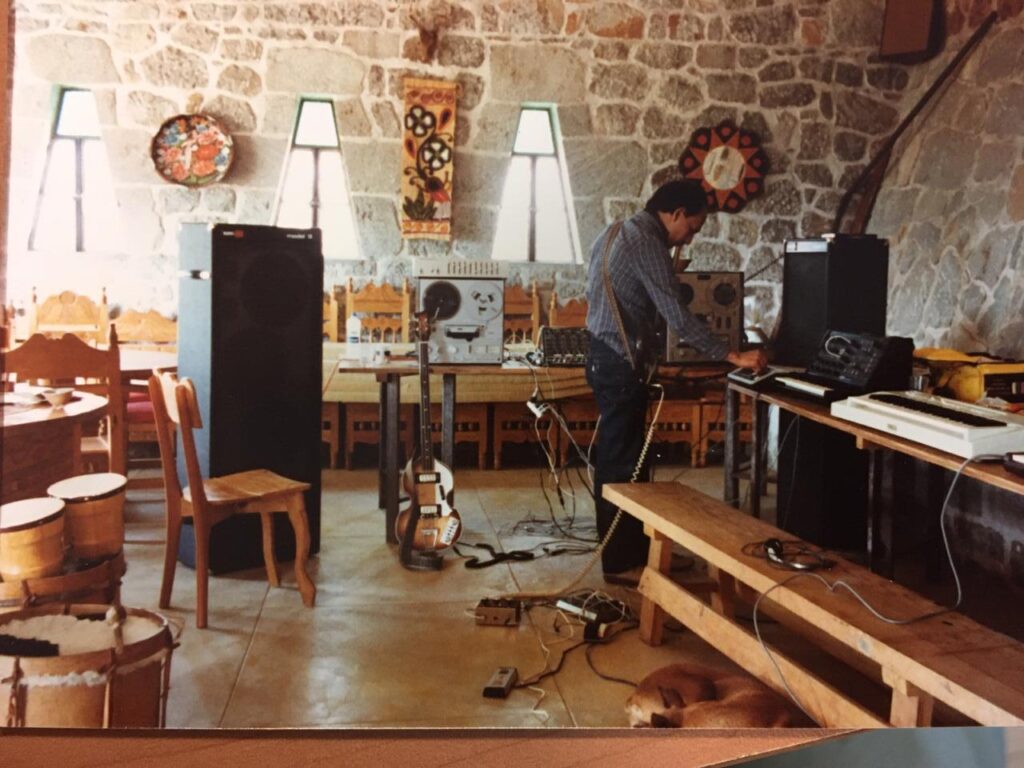

From the mid-80s through the 90s, a network of Mexican musicians embarked on a journey to craft a musical expression distinct from the mainstream musical culture that dominated the airwaves and record industry. Based around practices of collaboration, ethnomusicology, electronic experimentation and home-recording, these artists traversed territories at the very edges of genre and musical form… In an attempt to situate themselves within a culturally and historically complex landscape, many of the artists on the compilation reactivate ancient Mesoamerican music traditions, those of the Aztecs, Maya, and Olmecs. Their electronic compositions are intricate tapestries woven with the haunting melodies of pre-Hispanic flutes and ocarinas, resonating alongside the echoes of ancient percussive marvels like the teponaztli and huéhuetl.

To learn more about the origins of this forward-thinking Mexican electronic sound that in many ways paralleled the alternative scenes highlighted in Music from Memory’s landmark Outro Tempo – Electronic And Contemporary Music From Brazil 1978-1992 and the Spanish studio project Música Esporádica, we connected with a few musicians featured on the compilation: Antonio Zepeda, Eblen Macari, and Rolando Chía of Vistas Fijas.

Note: The interview below has been edited for clarity.

The music featured on this compilation is distinct from the mainstream sounds

coming out of Mexico during the mid-80s. Can you describe the musical landscape during this time and what led you to explore these more experimental, left-field sounds?

Rolando Chía: During the eighties, the music scene in Mexico City was heavily influenced by the media that promoted music based on tradition and marketability. Alternative musical expressions were then forced into scarce, clandestine spaces, mostly in certain suburban areas. The “tocadas,” as they were known, took place in open-air venues and were promoted through flyers, photocopies, and mimeographed sheets. The media would describe this underground music scene as violent, dangerous expressions, absent of social or aesthetic sense. Within such an environment, creating music was a challenge and daring adventure, to which was typically met with a sea of generalized indifference. My experiences as a musician, in context of bars, coffee shops, restaurants, and social events, finally made me know that the popular sounds, in those years, would not lead to anything that would please me musically. Thus, during the last years of the seventies, I began to study, in a self-taught way, different forms of alternative guitar playing.

Antonio Zepeda: There was a time in the mid-seventies when I had the opportunity to work as a music programmer in the radio station of the Secretaría de Educación Pública. The radio station became a sort guide of trends by programming music from all over the world and all eras. In other words, it was possible to program music that was entirely unknown to the masses, accompanied by small informative texts about the music and its authors in order to educate the public when introducing a genre too obscure for most listeners.

We would play almost any type of music that had quality, from ethnic music from all over the world, to abstract contemporary creations. We also programmed a lot of innovative music that was being produced at the independent level, particularly in Mexico City. There was a musical revolution brewing at that time with a lot of new and entirely independent groups emerging that did not necessarily follow the musical parameters of the past. That was the creative landscape in which I began to develop myself as a performer of pre-Hispanic woodwinds and percussions. In my case, composition was a product of discovering that magical ritual sound space.

What spaces were important to this musical movement? El Chopo, the outdoor flea market dedicated to rock and experimental music, seemed like an amazing cultural meeting point for this community of underground musicians. Can you share some of your experiences?

RC: El Tianguis de discos del Chopo was the urban catalyst of many different social expressions, including music. Its existence constituted a lifeline in the face of cultural and musical stagnation, and it stirred up the city. Since its establishment in 1980, it has gradually grown to become a point of convergence of ideas, cultural movements, and the axis of musical diversity of the last decades. With the launch of the Tianguis de discos del Chopo as a meeting point, slowly different venues began emerging where soloists and bands of the most varied styles performed. Forums, cafeterias, bookstores, bars and cultural centers began to appear in different places of the city; often surviving through hardship, improvising the spaces, and trying to find the best conditions to perform. As a soloist interpreting my guitar compositions, I developed a passionate activity playing in cafés, bars, universities, and cultural houses in the interior and in the city, in public festivals, and in the festival of the eclipse at Templo Mayor of Mexico City in 1991.

What else were you listening to at this time? The liner notes mention some influences coming from electronics, jazz, post-punk, and even pop.

RC: During the seventies, eighties and early nineties, I tried to pay attention to a wide variety of expressions, genres, performers, and ideas about musical practice. I had access to experimental, progressive rock, improvisation, noise, electronic, musique concrète, among others. By virtue of my musical interests, abilities, and skills, I was included in a few DIY alternative music compilations, which were distributed around the world. In short, I believe that my musical interests were not focused on a single genre, and my published works showcase my interest in experimental forms.

AZ: By the 1950s, Mexico City was an important Latin American cultural center. The greatest exponents were bolero, rumba, tango, danzón, mambo, and cha-cha-cha. Many extraordinary Latin American commercial artists sought recognition in Mexico as a prelude to success in Latin America. On the other hand, swing, jazz, and rock music were also present during those times and were very popular in Mexico. It was common to hear inspirational romantic Mexican ranchera and folk music from many parts of the country. Cuban and Brazilian music also had an important place in our hearts. In those times (1940-1980), the people of Mexico City were also fond of French and Italian music and cinema. The touch of Hollywood style and its music also left a deep mark on popular taste. European classical music had its own niche, but it was not very popular.

Since my childhood, I was always discovering music for myself within this enormous musical range. Above all, there were a lot of dance parties where knowing how to dance was vital to be able to develop on a friendly and loving level. If one did not know how to dance, one did not exist, one was nobody… Dance has always been as much a part of my being as music. I am a dancer who plays instruments and is touched by music; someone where body and spirit merge, moved by the emotion and sensations that music produces.

“Adjacent to the mainstream, there was an intellectual and creative community that had its own ideas and was in contact with cultures and trends beyond national geography and the merely Mexican or Latin American.”

Antonio Zepeda

Antonio, I'd love to know more about your practice with pre-Hispanic instruments. How did you approach combining these sounds with modern instruments?

AZ: The pre-Columbian instruments that I have been using since the beginning of my career are clay breaths: conch shells, flutes, ocarinas, and whistles. Some are up to 3,000 years old, while many are faithful replicas of original instruments of the past. For the past century, I have also played the classic instruments of pre-Hispanic percussion: Mayan, Nahua and Tarahumara drums, wooden and bamboo teponaztlis, turtle shells, clay pitchers, musical bows, and butterfly cocoons, as well as an endless number of scrapers and rattles of pod, guaje, and horn. In the pieces collected for this anthology, I use a combination of Mexican traditional instruments with ethnic instruments from other geographies, thinking above all about the musicality of the instruments and the possible combinations that I can offer to other collaborators to establish a musical dialogue.

It was a very interesting creative process since it was necessary to think about which spaces the other composer could expand upon. In general, one composer would provide the base and the other would complement it. It is marvelous how you can create new bridges that guide you by simply suggesting the direction of a piece. It is also extraordinary that something totally unexpected turns out to be perfect.

Besides the instruments themselves, are there other aspects of pre-Hispanic culture (philosophy, rhythms and customs) that have influenced you or inspired your music?

AZ: We know that pre-Hispanic music was closely linked to the religions of the past and that the surviving instruments are deeply connected to nature. Many replicate birdsong and speak to us of the optimism and candor of those who played them. They believed that music had been a gift from the gods to bring joy to the world. There are also breath instruments used in ritual settings related to the nine levels of the pre-Columbian underworld. Consequently, their sound is somewhat ghostly, metaphysical. Naturally, my practice of these instruments has gone hand in hand with my study of the cultures that generated them, their customs, their beliefs, their philosophy, their poetry, and their ethnographic, archaeological, and architectural legacy.

Eblen, your musical style also seems to be influenced by music from beyond Mexican or Latin American cultures. Can you share a bit of your musical background and guitar style?

Eblen Macari: My guitar style? Well, I’ve been honing it since I was young starting out with the classics from the ’60s: the Beatles, Simon and Garfunkel, Donovan, Cream. Then, I dipped my toes into the classical guitar world. But the real magic happened in the ’70s. My sister Janet and I participated in a university program that mixed European Renaissance pieces, Mexican tunes, and some of my own creations. It was a wild ride! As time went on, I got into musical fusion and started tinkering with electronics on my acoustic guitar, following avant-garde musicians like Ralph Towner and Pat Metheny. Later on, I would also soak up influences from World Music, Indian tunes, and the Middle East, especially Lebanon (where my ancestors hail from). All tied to my wanderlust for other places.