By the time The KLF released The White Room in 1991, they had already proven two things. First, that the charts were a system to be gamed. In 1988, as The […]

Two Decades On, ‘Techno Rebels’ by Dan Sicko Still Maps the Movement

A fresh look at the 1999 book that traced Detroit techno from Belleville basements to Berlin dance floors and the artists who carried it there.

Looking to add to your knowledge base? Chasing your next obsession? Read on.

First published in 1999, Techno Rebels: The Renegades of Electronic Funk by the late Detroit journalist Dan Sicko is one of the foundational texts on the birth of techno, written from inside the culture rather than at a critical distance. Although currently out of print, it’s worth tracking down if you’re interested in going deep on electronic beat music, or you can check it out through the Internet Archive. Editor Nathan Brackett explains the aim of the book, published when there were few on the topic.

“The demand for thoughtful, informed writing about techno is now greater than ever,” Bracket writes in the preface. “The music is over fifteen years old, and the entire sweep of the first part of its history is beginning to take shape. At this moment in the late 1990s, it’s as if techno is catching its first real breath: books are being written, and there’s even a whiff of nostalgia in the air for the music’s early days. It is comparable to 1977, when Charlie Gillett wrote Sound of the City, the first definitive history of 1950s rock’n’roll, or 1989, when Greil Marcus started talking about punk’s ‘Big Picture’ — enough time has passed to take a long view, but the landmarks and characters haven’t yet faded into distant memory. If the first draft of music history is whatever journalists are writing as something is happening — the first reviews, features, and such — now is the time for the second, more careful draft.”

Sicko’s draft remains essential because he reported extensively on the rise of his city’s techno scene, and became a central documentarian of it. Writing for The Detroit News and immersed in the community he covered, Sicko didn’t treat the movement a local music story but an international movement with roots in Black futurism, postindustrial geography and the peculiar tension between Midwestern isolation and global ambition.

He’s particularly prescient when discussing the independent streak that has long defined Detroit techno, especially Underground Resistance and the city’s second wave in the 1990s. When Sicko speaks to UR’s Mad Mike Banks about UR and major labels, their foresight is worth noting.

“We had a college kid call us from a major saying “You guys looking to get a deal?,” Banks told Sicko. “Jeff [Mills] told him, ‘No, we’re a record label.’ Then the kid says, “I know. I know, but do you want a deal?” [Banks laughs.] A real asshole! These labels just don’t understand that there’s a whole generation of people out here that are tired of being prostituted by major record companies. [Companies] are real frustrated that basement labels are placing way higher in the charts than they do.”

Techno Rebels arrived at a moment when the first generation of Detroit producers had already transformed dance floors from Berlin to Tokyo, but the story of how it happened remained fragmented, passed along in Urb and Jockey Slut interviews and liner notes and word-of-mouth. Sicko gathered those threads and gave them structure. He traced the arc from Belleville High School to European megaclubs, from radio shows and basement studios to labels like Metroplex and Transmat, anchoring the narrative in the work of the so-called Belleville 3, Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson, without reducing the movement to a tidy origin myth.

What distinguished Sicko’s approach was tone. He wrote with the clarity of a daily journalist and the patience of someone who understood that scenes calcify. His “second draft” ambition wasn’t about canonizing heroes so much as situating them: connecting the music to Kraftwerk, Parliament-Funkadelic, Chicago house, local radio and the economic hollowing out of Detroit itself.

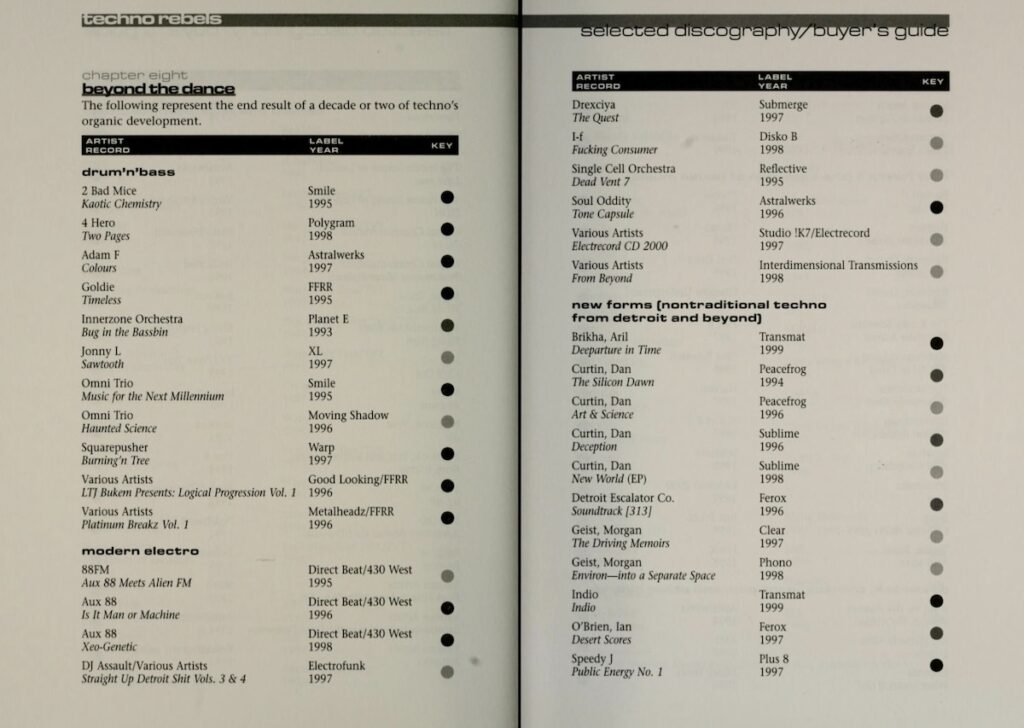

Sicko died in 2010 at 41, but the book endures because it captured techno at that precarious hinge, old enough to historicize, young enough to still feel volatile. Perhaps best are the recommended listening lists near the end of the book. Dividing the sounds by decade, he paints the picture of a movement in motion, one that shifts from early electro experiments and Belleville minimalism into harder European strains and the sleek futurism of the 1990s. The lists function as guided pathways, an invitation to hear how ideas mutated across labels, aliases and continents.