Read a very long, very fascinating interview with Ralf Hutter and Florian Schneider from Synapse Magazine, 1976. In 1976, Kraftwerk sat at a strange, newly powerful crossroads. Autobahn […]

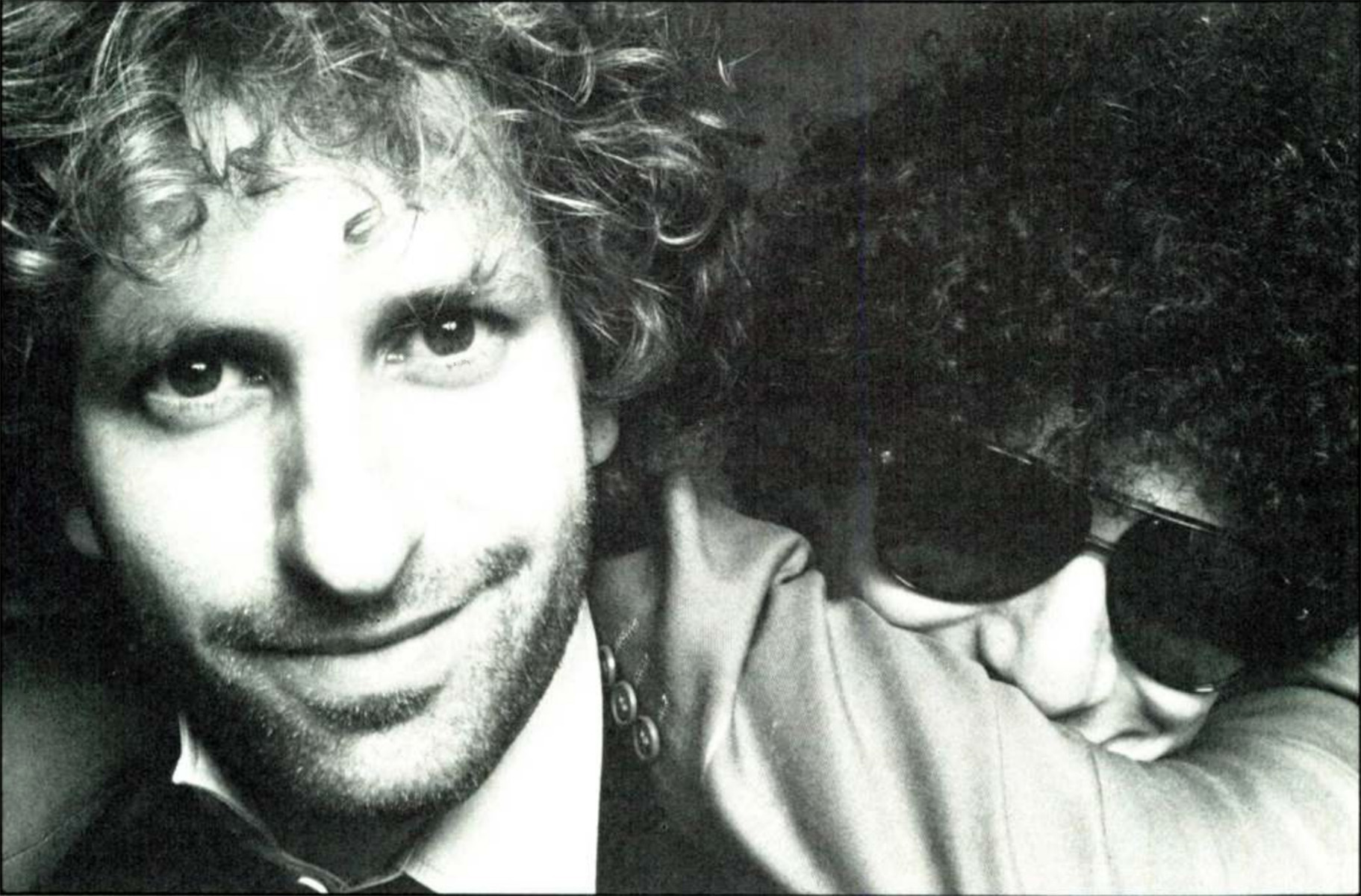

Was (Not Was): All Over the Road with Two Motor City Outcasts in a Studio Tornado (1984)

Read an archival 1984 Musician Magazine interview with cult favorite Detroit mutant funk duo Was (Not) Was.

“When black people hear our music,” proclaims Don Fagenson, “they know we’re white. Even our funkiest stuff. I think it happens to be a plus. I’ve seen black kids pause and say, ‘Where the heck does that come from?’ It’s a perversion of their culture…and I think they’re entertained by it.”

Don Fagenson, a.k.a. Don Was, and his partner David Weiss, a.k.a. David Was, are the principals behind Was (Not Was), auteurs whose music, like their name, thrives on the tension of meeting opposites: black/white, Detroit/L.A., art/commerce, fun/funk, and even—sacre bleu— Ozzy Osbourne/Mel Torme. All may be appreciated in abundance on the Wasbros.’ second, thoroughly audacious album Born To Laugh At Tornadoes, an LP which has sent writers, critics and press agents falling over their word processors in attempts to define the pair’s unique melting pop. It’s an approach which may well court commercial suicide, but for the moment Fagenson and Weiss have at least lent new meaning to the term AOR: All Over the Road.

“When I was growing up,” Fagenson explains, “I really liked the Beatles White Album’, never was there more of an anthology, from ‘Revolution #9′ to ‘Martha My Dear,’ and yet it made perfect sense. Our albums come from that sensibility, that this is more exciting than a band playing two singles and then eight more songs that sound like singles but aren’t as good.

“My fear,” he goes on, “is that if you really homogenize everything and come up with this combination that aims for mass culture, you wash out the extremes. I would hate to have a coffee colored thing happen—you end up with Lionel Richie and Kenny Rogers everywhere. I think it’s much healthier to have your choice of country stations, jazz, rock, public, a news station…and they all stand for something. I like to view the radio dial as a whole.”

“While my contemporaries were memorizing song lyrics, I was thinking that the real call of the wild was in jazz and classical. I’d blow stuff like Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and sit there crying…”

David Weiss

That vision may well be the most cogent explanation for the perverse panstylism of the Was brothers’ records—music which cuts across the pop spectrum from deep funk to cocktail jazz, yet never dilutes or homogenizes the “roots” music which is ineffably Detroit’s. At the same time, Weiss’ consistently weird lyrical characterizations, fused with Fagenson’s imaginative production and cameo castings (which in addition to Torme and the Oz include such Detroit homeboys as Sweet Pea Atkinson, MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer, Doug Fieger and Marshall Crenshaw, lend Was (Not Was) the veneer of a street level Steely Dan. “I suppose David would be more the poet and I’d be more the clown,” Fagenson muses. “But it’s not that defined. We grew up together, a couple of blocks apart—he’s been my closest friend since we were about twelve. We’ve been doing this for a long time—writing music, playing with tape recorders….”

David Weiss remembers the beginning, at Clinton Junior High. “I saw him in the eighth grade talent show, playing acoustic guitar and singing ‘Midnight Special’ and something by Dylan. I thought he was the greatest; he was radiating something special, and was probably a little cooler than any other of my peers.”

For one thing, he had a tape recorder. “It only cost $130,” Fagenson amplifies, “but you could bounce track on it. We used it until I was about twenty, then we moved up to a Revox.”

“We were doing stuff like the Firesign Theatre—skits and things—and some music, too,” says Weiss, whose parents had indulged his meandering musical interest as it moved from piano to guitar to saxophone to flute. “We painted our names on guitar cases and pretended we were important,” he recalls with a wink and a grin. “We were going to Montreal once, and the customs guy came on the bus as we crossed over into Canada, and said, ‘Open the guitar case.’ There was no guitar in there—only my socks and underwear. Didn’t have a guitar.”

For Weiss’ part, “While my contemporaries were memorizing song lyrics, I was thinking that the real call of the wild was in jazz and classical. I’d blow stuff like Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and sit there crying, because I’d read that Berlioz sat on a park bench writing this stuff with no piano, crying. I identified with him sitting there, wrenching his guts out writing a symphony.

Weiss can quote German philosophers and psychoanalysts to explain himself and his partner now, but when pressed, he’ll admit that “the real reason we started making records was we couldn’t get girls. We’d go down to Woodward Avenue, roll down the car window, and some girls would roll down their window. You’re on the spot, y’know? You just have time to get one thing out over the din of the engines.”

“We had some great lines that failed,” Weiss adds with a rueful laugh. “We thought of some non-sequiturs like, ‘Would you like to buy a house?’ Then we’d come home frustrated and make tapes.”

While David was finishing college, Fagenson—having dropped out in his first year—was paying dues playing bass in a cocktail lounge and working in a Tascam-equipped 8-track studio located in what he describes as a rather treacherous neighborhood: “The studio was on top of a warehouse. The machines were mounted on shipping crates—very funky. We had a live echo chamber and a vault downstairs, and sometimes when we turned up the echo return we could hear people breaking into the building. We’d just lock the elevator and stay upstairs….”

Jack Tann, an “early patron saint” of Fagenson’s (according to Weiss), got a job booking time at the Sound Suite and brought him along. “He saw Don’s potential,” says Weiss, “and it was a good thing, too: Don was going nuts playing in this bar and being a hack in the studio producing everybody’s copycat sounds.”

By this time both men were married, which cooled their partnership to a certain degree, and Weiss had moved to Los Angeles and gotten a job as jazz critic at the Los Angeles Herald Examiner. He was still sending back lyrics for Fagenson’s various projects when Don’s restlessness reached a crisis point. “He called me in California, desperate, saying he was totally broke and sick of cutting all these one-off, make-abuck deals. He said, ‘Let’s get together and do something that counts.’ Otherwise, he said, he was about to rob a drycleaner to get some money. He had the place picked out; there was a teenage girl at the counter.

“Here was a guy who couldn’t have picked a flower from someone’s garden, and he said he was going to rob a cleaners.” Impressed with his brother’s desperation, Weiss returned to Detroit, borrowed $400 from his father to pay for studio time and musicians, and—“Voila! Was (Not Was). We recorded ‘Wheel Me Out’ and a B-side, ‘Hello Operator…I Mean Dad…I Mean Police…I Can’t Even Remember Who I Am,’ and we sent them to Michael Zilkha at Ze Records. Michael listened,” says Weiss, “and the rest is histoire.”

“I used to worry about ‘growing up’ in the music business, because I hadn’t learned to adapt to time restrictions. But you don’t have to do that —you can totally bypass that whole method of working.”

Don Fagenson

The name Was (Not Was) was coined by Fagenson’s son, Anthony, who was one-and-a-half years old at the time and just discovering the concept of oppositeness, according to his dad—”that something like could be and not be,” says Fagenson. “He was saying things like, ‘Long, not long,’ and one night it just came out: ‘Was, not was.’ “The best thing about a good non sequitur is that is seems like it means something,” adds Weiss. “It’s got that suggestive ring to it.”

Fagenson is now very much at home in the Sound Suite, which he says, “looks like a bombed-out dentist’s office buried in the middle of Detroit.” The neighborhood is funky, Fagenson admits, “but the studio itself is really nice. It’s got a great street vibe, and the room is unbelievably accurate.” Fagenson works alone much of the time, and admits that if it weren’t for some creative booking agreements, Was (Not Was) wouldn’t be able to afford to work the way they do, recording a song at a time from start to finish. While making Tornadoes, for instance, Fagenson had the Sound Suite booked “from midnight on, every night. If there isn’t a session booked for the next day, I’ll stay in and work straight through.

“I used to worry about ‘growing up’ in the music business, because I hadn’t learned to adapt to time restrictions,” he observes. “But you don’t have to do that —you can totally bypass that whole method of working.” The principal players on the Was (Not Was) projects are professional musicians, but they also happen to be friends. “You pay them fairly, but it’s not based on three hours going by. Most of the people who work for us hang out after their sessions are finished. It’s loose—and it’s fun. I can’t work any other way.”

Most members of the Was repertory are old acquaintances —Fagenson knows Marshall Crenshaw from the days when that songwriter was fronting a local band called Astigafa. But Fagenson isn’t averse to taking a flyer either; the appearance of Ozzy Osbourne came about about because he and Fagenson share the same attorney. “We were having trouble finding the right singer for ‘Shake Your Head,’ and Ozzie…it was so absurd we had to try. He was perfect! I couldn’t believe it, but like any artist, he’s tired of being locked into that one thing. He’s definitely the real item, too,” Fagenson notes admiringly. “This is definitely the guy who pissed on the Alamo.”

Fagenson is an exponent of a practical, seat-of-the-pants production philosophy which, he calls “Zengineering,” the essence of which is that “the best way to engineer is not to engineer at all.

“People are concerned about distortion from a tape machine or a mixing board, but the worst distortion I’ve ever found comes from stopping a session for half an hour to figure out whether you should use an SM58 or an RE-20 on the foot (or kick, if you’re on the West coast). Stick the microphone in the drum and cut the song* As long as the feeling is there, it doesn’t really matter what a record sounds like.” It does matter, of course, but Fagenson says, “If it came down to a clear-cut choice—which it rarely does—I’d take a track that’s distorted if it had the inherent feeling to it.”

Consistent with the principles of Zengineering, Fagenson says that while he rarely wastes hours searching for the perfect place to put ambience mikes on a drum kit, on occasion he’s crawled around looking for a “stupid” place to put one. “We’ve dropped a mike down a garbage can and put it across the room, then had the guy play the sax facing the mirror. That was for ‘Someone Could Lose A Heart,’ on Sweet Pea Atkinson’s album,” says Fagenson. “The saxophonist, David McMurray, and I, just got sick of hearing it the same way all the time!’

Zengineering also has a lot to do with throwing the book out the window and playing by ear. “That’s the only way you come onto new things.” The trumpet solo on “Empire Brain Building,” for example, was originally played (by Hannibal Petersen) on Tornadoes’ opening cut, “Knocked Down, Made Small.” “We wild-tracked it onto quarter-inch tape, VSOing it to match the pitch of ‘Empire Brain Building,”‘ Fagenson chuckles.

“Then we cut the middle in about thirty pieces, tossed thim into the air and reassembled them at random, and bounced it back onto the new song. It was a great solo on Knocked Down,’ but we needed one for ‘Empire Brain Building.’”

But the biggest kick in making Tornadoes, both Was brothers agree, was getting Mel Torme to sing their cockeyed ballad. “Zaz Turned Blue.” Once the song was written it was evident that the Velvet Fog was the only man to sing it, “but,” says Fagenson, “we were prepared for him not being able to get into the lyric. It’s clearly not his usual song—I don’t think he ever sang a line like, ‘Steve squeezed his neck.’ And it’s not something he needed to do, having won a Grammy the week before we called him. But David knows him from being a jazz critic, and they’ve become friends.”

Torme agreed to give the tune a shot; the Was brothers sent him a tape, and “he lived with it for two and a half weeks before the session. On the drive to the studio he said, ‘Tell me more about this guy Zaz.’ He wanted to know everything about the situation.”

Torme “found nuances—both musically and lyrically—that David and I didn’t even know we’d written into the song,” says Fagenson. “His accompanist. Mike Renzi, played piano and wrote the string charts. They have a great chemistry between them, and they transformed the song. It was a real thrill! He killed us on the first run-through! We cut four takes, but we ended up using the first one.”

One can only imagine the looks on the faces of the Miami Beach retirees who witnessed the spectacle of two grown men—Fagenson in mirrored shades and a disreputable grey suit—walking along the sand repeatedly slapping five while their blaster played that familiar voice. “We must have listened to it fifty, sixty times,” Weiss chuckles. “We couldn’t believe it—‘He sang it!’ It was one of the gases of my life.”

This article was originally published in 1979 for Musician Magazine and has been posted here digitally for archival purposes. Check a scan of the entire publication here.