One final list to close out the year… Our personal favorite discoveries of 2025. We don’t often share our faces here at In Sheep’s Clothing. Whether it’s due […]

Labels We Love: Ansonia Records

A conversation with Ansonia’s Liza Richardson and Souraya Al-Alaoui about the label’s history, revival and future, tracing a catalog of merengue, jibaro, bolero and salsa that has anchored Latin music since its founding in 1949.

Ansonia Records was founded in 1949 by Puerto Rican émigré Ralph Peréz, who built the label to serve the growing Caribbean communities of New York. Instead of chasing crossover hits, Ansonia pressed merengue, jibaro, bolero and charanga as lifelines for the diaspora. Across four decades the label issued some 5,000 recordings — roughly 400 albums — featuring figures like Daniel Santos, Cortijo, Myrta Silva, Trío Matamoros, and early appearances by Celia Cruz and Ismael Rivera. Though Spanish-language radio spins and record sales were never tracked by the industry, the music endured, echoing in family gatherings, on dance floors, and now in TikTok trends and Bad Bunny shout-outs.

Today the label is steered by Liza Richardson, longtime KCRW DJ and acclaimed music supervisor for series like Friday Night Lights, Parenthood, Narcos and Watchmen. She first discovered Ansonia while sorting promos at the KCRW library and later befriended Mercedes Peréz, Ralph’s daughter, who ran the label after active recording ceased. After Mercedes’s passing, Richardson worried Ansonia would vanish into a corporate vault. In 2018 she bought it herself, moving boxes of tapes, negatives and session notes into a Venice office and enlisting archivist Souraya Al-Alaoui to help bring order to the chaos.

Richardson and Al-Alaoui have since reshaped Ansonia as both archive and living imprint. They’ve relied on historians and writers to frame the catalog’s cultural weight, and in recent years folded in contemporary voices like Meridian Brothers, Rita Donte and Miramar. The result is a label that bridges eras, honoring the history of Latin music in America while ensuring that these recordings remain part of the present.

In Sheep’s Clothing Distribution is proud to be working with Ansonia, and we’re genuinely excited to help bring their new releases into the world. We caught up with Liza and Souraya to talk about Ansonia and its revival. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ansonia Records titles are available now through In Sheep’s Clothing’s online webstore. Shops can reach out to [email protected] for wholesale pricing!

Can you each tell me a bit about your backgrounds — what you were doing before Ansonia and how you came to work together?

Liza Richardson: Through my years of fascination with music from all over the world, as a DJ on KCRW, I got to know this label called Ansonia Records. It was, or is, a US-based label that started in 1949. It’s always been independent, and they made records from 1949 to about 1989. It was started by Ralph Peréz. He moved to New York from Puerto Rico during a time when there was a lot of migration from the Caribbean – the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Cuba.

Ansonia started as (and still is) an independent label. It was meant to appeal to the diaspora. It was never meant to crossover. I mean, you know how for instance, Nat King Cole made an album in Spanish, those songs were kind of crossover-ish and meant to appeal to a broader audience? Ansonia wasn’t like that. It was meant to serve specific communities.

Although Ralph Peréz was from Puerto Rico, most of the first recordings on Ansonia were Dominican. We have so many amazing, beautiful merengue records from that era, from the early 50s. That’s what got Ansonia going.

At KCRW, when I first started I worked in the library with Jason Bentley and Chris Douridas, we received packages every day, as you did in the 90s, boxes and boxes full of CDs. Opening them and going through them, I discovered this label, Ansonia. It looked cool. I picked up the phone and reached out and got to know the woman who owned it. She was the daughter of Ralph Peréz. Her name was Mercedes Peréz Glass.

She ran the label after they stopped recording. It became a distribution company in the 90s and into the 00s. But they didn’t really have a website or a Facebook page, or anything online. So it got a little lost as the age of digital music took hold. But I still always kept in touch. Throughout my years as a music supervisor working on projects that required Latin music, I’d always go back to Ansonia. I felt it was a secret resource. Mercedes and I built a good friendship through licensing her music.

I never met her in person, unfortunately. One time I called her — I think it was 2016 — and her son called me back saying that she had passed away. That was obviously sad. A year or so later, a light bulb went off. Since it’s an independent label, I was afraid it would get sold to a major or a VC company and it would get lost.

I had the idea — what if I could be the person to steward it? It was actually my accountant’s idea. I didn’t even think anything like that would be remotely possible, but my accountant, who’s one of my best friends, heard me talking about it a lot, so he kept pushing me to try.

Eventually I brought it up to Mercedes’ son, Gerry Glass. At first he said no, they weren’t planning on selling it. But a year after that he called me and told me they were. There were a few offers but I convinced him to accept my proposal. So I felt so lucky, Randall. It seemed like such a long shot for me at the time, it was. I feel incredibly lucky to have been in that place at that time. Now it seems so natural. An odd pairing, me and Ansonia, but I was ready to put everything into it.

Around 2018 I was able to purchase Ansonia and move the label to Venice, where we have a little office in the Venice/Mar Vista area. If you come back and visit sometime, you’ve got to check it out. We have all the old tapes, catalogs, notes from the sessions, accounting records, album art, negatives.

Oh my God, that sounds like heaven on earth. I would love to.

LR: It’s really cool. We even have multitracks on some of the records from the 60s and beyond. So in 2019 my accountant kept telling me, “I’ve got the girl who can run it for you.” I’d say, yeah, yeah, I’ve got this, I know people. But I had all these unmarked boxes and a full time job and I had sort of a panic attack and I needed to hire somebody immediately. I called Arnie and said, “Who’s that girl you mentioned?”

So Souraya came over, met with me, and I hired her on the spot. She seemed perfect and I just went with my gut. One thing that impressed me was that she had some experience in college working in an archive, and she just seemed like a nerd like me.

Souraya Al-Alaoui: I got really lucky, to be honest. I didn’t have any record label experience. The closest was working at a music tech startup during the early days of streaming. It was focused on figuring out the best way to make money for artists. The whole idea was to stream music based on what was playing live near you.

Then I went back and got my masters in broadcasting. I was interested in working in radio. But as soon as I graduated, my father had a stroke. I literally took two, three years off where I wasn’t working, just taking care of him. Eventually I thought, okay, I need to get back to my life, I need to find work.

My brother started asking around: “Hey, my sister needs a job.” He’s really good friends with Liza’s accountant. That’s how I got mentioned, and when I finally met with Liza and she told me about the label, I thought, oh, that’s so interesting — but I don’t think it really sank in until I got to the office. Everything was in boxes. I saw the tapes and thought, whoa. Then I started looking at papers and researching.

I was learning about the label as I unpacked the boxes. It put me in a really good position, because I got to know everything. At first I didn’t understand. I thought, why do they have so much Ramito? Who is this guy? Only to find out he’s one of the most important figures of folkloric Puerto Rican music.

At that time, merengue all kind of sounded the same to me. But then I kept listening. I realized this is the kind of music that takes time for your ear to adjust.

LR: A lot of types of music, when you don’t know it yet, at first can sound samey. Jibaro for instance, which Ansonia has so much of, it has a form or formula and to the uninitiated ear, all sounds very similar. Now it doesn’t at all.

SA: Yeah, that’s exactly it. As I was getting to know the catalog, I was discovering music I’d never heard before. I didn’t have experience with it. I knew salsa and the obvious things, but this was new.

I thought, wow, we’re in an interesting position. We’re trying to reach people who are like us — people who may have never come across this music. How do we reach them? How do we make it interesting to them in the way it became interesting to us?

So early on, we leaned on writers, reviewers, historians, to bring more context. We didn’t just want to say, “Here’s a Dominican merengue.” Positioning the music historically and socially was important, and we knew we had to include experts.

When you look at the catalog, can you quantify it a little bit first? Like, how much is there?

SA: You mean the numbers?

Yeah. How many records were released?

LR: It’s about 5,000 sound recordings — around 400 albums — Discogs shows more like 500 but those include some of the music distributed by Ansonia, not necessarily part of the catalog. Publishing-wise, Ansonia has about 800 copyrights. The rest are famous songs owned by other publishing companies — Peer Music, Sony, Warner, etc.

SA: The label started in 1949, so a lot of the early releases were on 78s. Many of them were reissued on LPs. A lot of the early LPs were basically “greatest hits” collections of those 78s. Especially with the merengue material — compilations of earlier releases, reissued as the technology advanced.

And just so I understand — when you bought the label, did you buy their dead stock as well? Was there stock on hand?

SA: Yeah. Whatever the label had, came with. It was all together — tapes, 78s, 45s, LPs, and a little dead stock but not much. And of course, the rights.

I see. Okay, so when you look at the catalog, which artists or recordings feel most central to the story?

SA: In terms of commercial success, it’s hard to pin down. Like Liza mentioned at the beginning, the goal was to reach the diaspora, not the broader US charts.

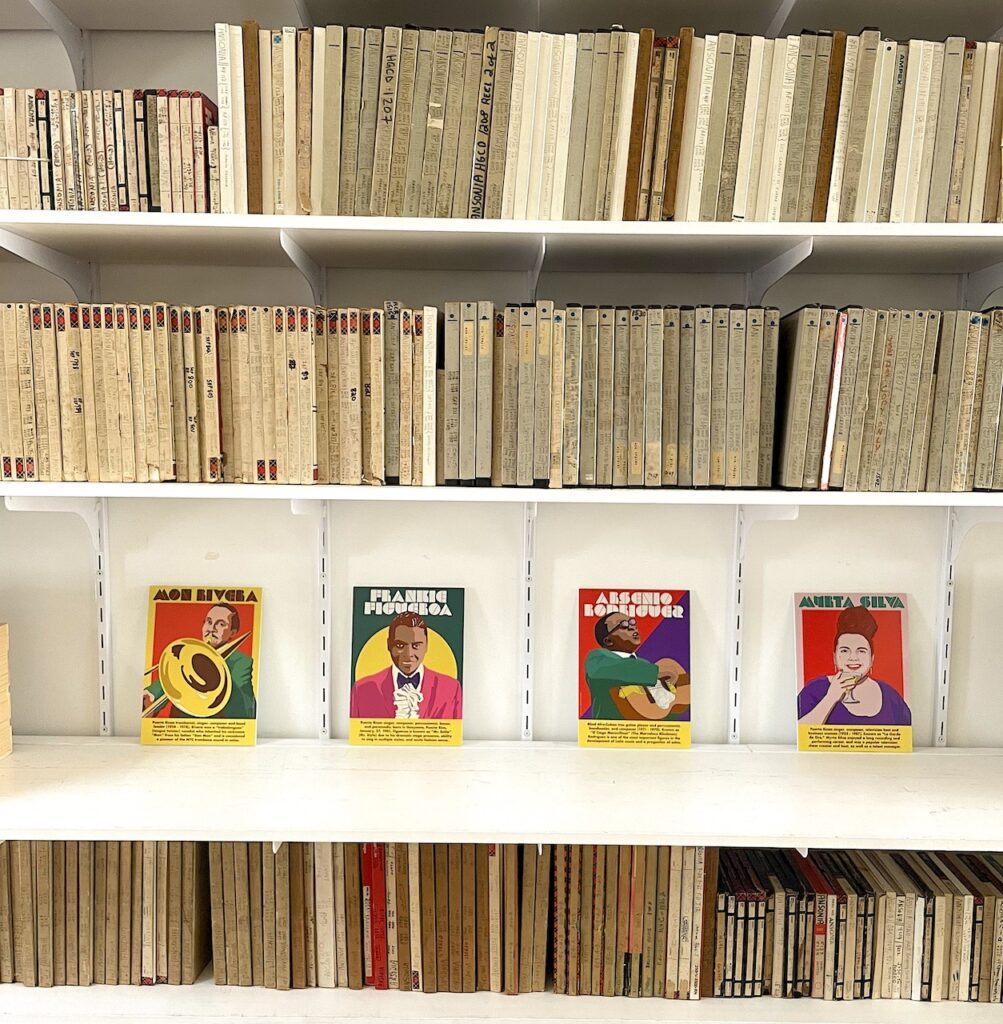

Noro Morales — we have only one album by him but it’s the one that’s really influential. It does well for us on streaming. Arsenio Rodríguez only had two releases with Ansonia, but because he’s such a giant, those are important. Belisario López — his charanga album has one song, En casa de estanislao, that has a lot of dances on TikTok. Myrta Silva — huge in her own right, so just having her recordings is amazing. And Cortijo — I don’t know how much commercial success those albums had at the time, but he’s so important that I’d count him as a major artist. We know the merengue albums were popular, but were they commercial successes? We don’t know.

That makes sense. Spanish-language radio stations weren’t being consulted on spins, so it’s not like we can count rotations.

LR: Exactly. I also want to mention Daniel Santos — we have a lot of albums by him, and he was a big star. Trío Matamoros too — a really important Cuban group. And to bring it to today, Bad Bunny has name-checked both Cortijo and Chuito as inspirations for his latest album, which is amazing — very emotional for us.

SA: We also have early recordings of Ismael Rivera, who’s a huge figure in Latin music. He was part of Orquesta Panamericana, and a few of the songs he recorded there are on Ansonia. El Charlatán especially — that one I know was a commercial success. People know that song even if they don’t know Ansonia. And we have four Celia Cruz songs from very early in her career.

Can I ask you a little bit about strategies for getting this music into the ears — and onto the phones — of younger generations? How do you work social media? Can you talk a little about that?

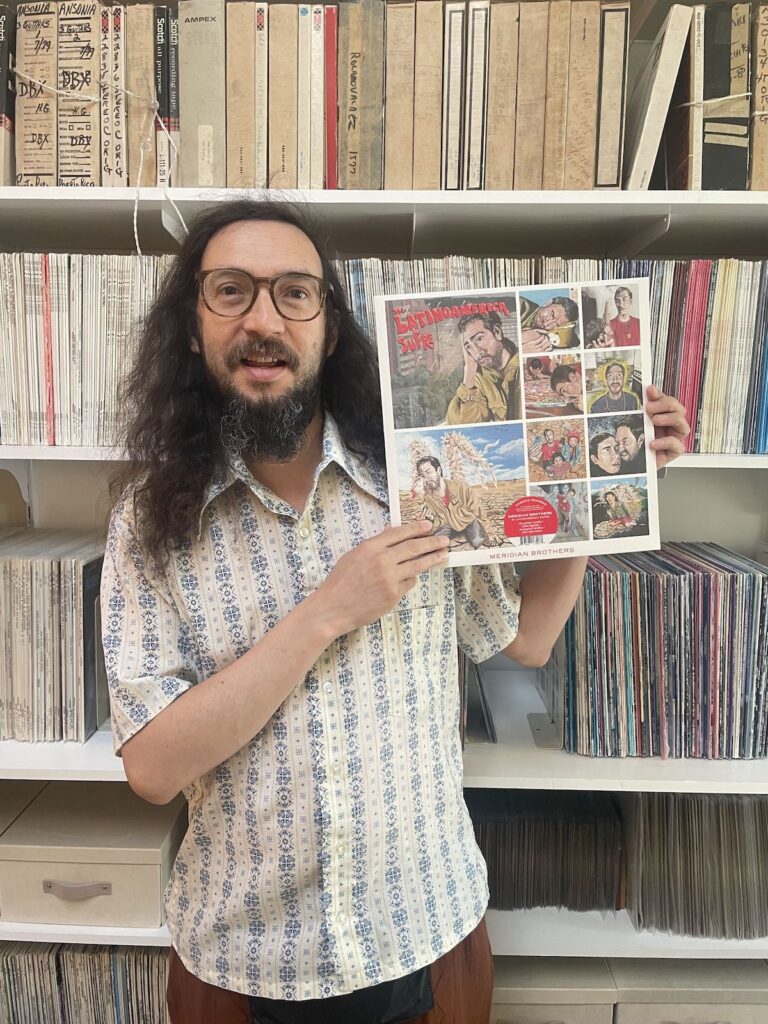

LR: Souraya can answer that. But this also brings us to our new music. I wouldn’t say we have a specific sound, but there’s definitely strong DNA. When we look for new music, we think about that. We’ve released music from three modern artists in the last couple years, so we hope the new music brings attention to the catalog. Meridian Brothers, Rita Donte and Miramar are the three so far. Next year we’ll have another artist, but that’s a secret for now.

Tell me about your contemporary signings.

LR: Meridian Brothers came to us through Camilo Lara of Mexican Institute of Sound. He introduced us to Eblis Álvarez. I already knew the music and was a fan, but to hear that he was a fan of Ansonia and wanted to be on the label — that was huge. Done deal.

Then journalist Beto Arce shared one of his favorite artists with us — Rita Donte, a Cuban singer-songwriter living in Mexico. Because of his introduction, we discovered her and absolutely adore her.

And Miramar came to us through Pablo Yglesias, a journalist who’s written books on Latin American album art and is a major authority. He writes a lot of our bios for Bandcamp and such. He introduced us to Miramar, who live in Richmond, Virginia, and have Puerto Rican and Latin American roots.

So we take tips from friends and connections. We do get sent things now and then, but haven’t found anything that way yet. Mostly it’s friends saying, “You’ve got to hear this.” We resist at first, saying we can’t afford to do another record right now — then we fall in love with it, and we have to.

SA: It’s funny, the Meridian Brothers were the first new artist presented to us. At the time, Liza and I had said, “Let’s focus on the catalog.” But when Meridian Brothers came up, we couldn’t say no. One, we were both already huge fans. Two, they already had a reputation and a solid fan base. Not to mention, a very well defined aesthetic. We saw it as a great opportunity to collaborate with an artist we admired.

His idea was to revisit 70s salsa, which fit perfectly with us — kind of like Ansonia’s rebirth. He created a fictional salsa group for the project, another kind of rebirth. It felt perfect. We also saw it as a chance to reach a younger audience that’s into current Latin American music.

My wife and I were in Kansas City a couple weeks ago. There’s a great listening bar called XO, and they were playing a Meridian Brothers record when I walked in.

LR: Amazing! My dream is to walk into a restaurant and hear our music.

I had to Shazam it. This place has a beautiful sound system, playing it at proper volume. People really heard it.

SA: Nice. So cool.

I know you can’t share everything, but can you talk a little about upcoming plans?

SA: We’ve put so much energy into the new artists. The Miramar release, the Rita Donte release — they were back-to-back. Now we want to shift focus back to the catalog. Liza mentioned we do have something new coming out next year, so that will be happening. But we’re also really thinking about catalog.

We did the Salsa Con Estilo compilation in 2024. We obsessed over that — put our heart and soul into it. That was in collaboration with Pablo Yglesias, who’s a salsa expert. It was really well received, and it reintroduced the salsa from the catalog. We want to do more compilations, reissues.

We have a reissue coming later this year — In Sheep’s Clothing will carry it. Bad Bunny, as mentioned, has been referencing Chuito and Cortijo. The whole ethos of his latest album is: “Check out the history of Puerto Rican music. Salsa is great, but look at bomba, plena, jibaro — this is just as important.”

If this is our chance to piggyback on that and tout that history while it’s being celebrated, we’d be stupid not to. So we’re re-releasing a great album by Chuito by Christmas time this year.

Did you see any data upticks when Bad Bunny started mentioning those names?

SA: Yes. So, like Liza said, me and Charlie have been doing the social media. One of the videos we did for Instagram was about Chuito. That video, we didn’t promote it, didn’t boost it, just posted it. And it did crazy numbers. For us, anyway. We’d never seen numbers like that before.