Transparent clarity, deep bass, and “Invisible Sound” from German audio company ADS. Background: One of the lesser known hi-fi brands of the ’70s, ADS (Analog and Digital Systems) […]

Want to channel better sound into your hi-fi system or headphones? Buying a DAC will change your listening life

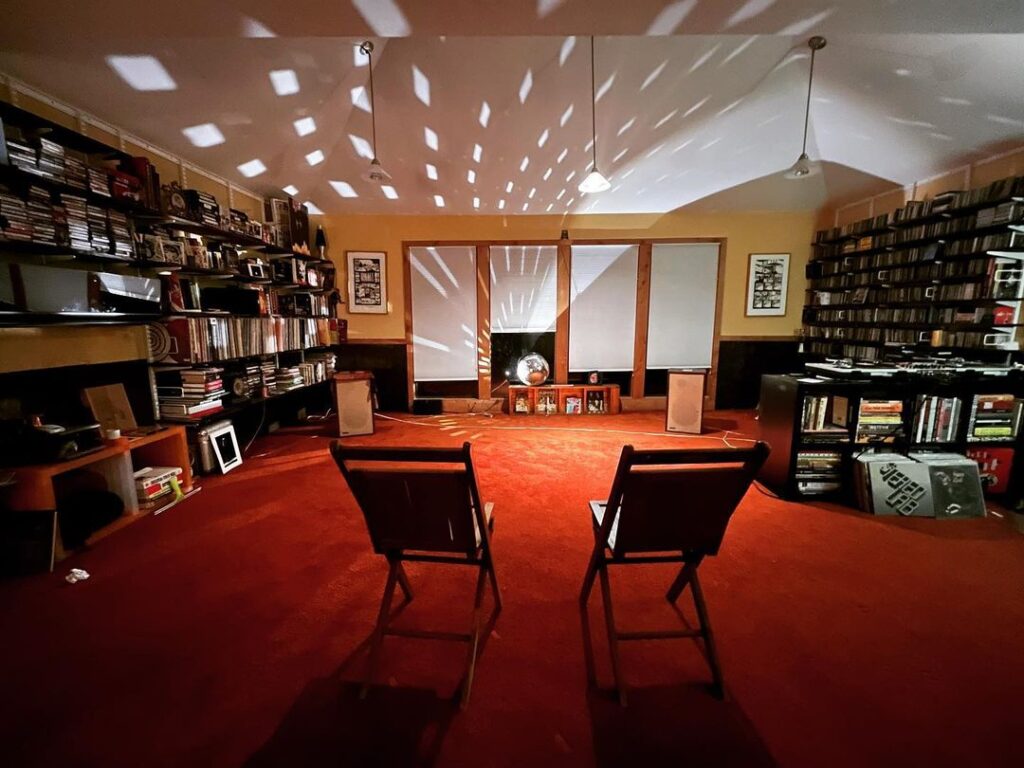

One listener’s experience having his sonic mind blown…

Getting lost in music is an act of vanishing, and if the ultimate goal of high-fidelity sound, vinyl culture and deep listening is to establish the clearest possible connection between the soundwaves that musicians made in the studio and your wide-open eardrums, it should hardly matter whether those waves arrive through analog, digital, carrier pigeon or some mystical signal generated by God herself.

As long as they make their way to the pleasure receptors, these missives in their purest form are format-neutral.

One convincing argument goes that embracing vinyl and hi-fi culture shouldn’t require a whole-hog dismissal of digital music, especially considering that high-definition streaming and download services offer sound quality that greatly surpasses the dull, compressed thud of MP3s in the days of yore and the tinny sibilance of pre-2000 compact discs. Vinyl will always reign supreme for reasons too many to enumerate, but the truth is, if the sole intent is to allow your favorite artists’ recordings to overtake you, when deep inside your favorite Lee “Scratch” Perry, Autechre or Karen Dalton song you won’t be thinking about the “hows” of its source but so absorbed in the wonder of it all as to forgot such non-cosmic concerns.

Before we go any further and in the spirit of full disclosure, this post is about two products created by the British company Cambridge Audio, and was commissioned, in part, by them. ISC agreed to this effort, though, because long before the company reached out, the Cambridge Audio DACMagic 100 had already changed the way I think about 21st century listening and sound, and its machine expanded my world when the pandemic hit. Regardless, armed with the DAC, I found myself spending hours in my music room time-traveling to sonic realms in ways I’d not before imagined.

One reason why LPs, cassettes and CDs are being snatched up by generations reared on music streaming, MP3s and instant YouTube gratification might be because this time three years ago we were collectively faced with many, many hours of free time while starved of what to many of us was our lifeblood: live music. An experience that we all took for granted –– spending uninterrupted, intentional time getting lost inside music at concerts or on dance floors –– disappeared.

Seeking alternative ways to scratch that itch, we rediscovered an endeavor that had faded with the rise of Walkmans, boomboxes, iPods and other portable music disrupters: sitting around and spending serious, uninterrupted time with physical music and committing to the intention that comes with dropping a needle or flipping the side. Not in the background. In the foreground. So it overtakes you and, ultimately, carries you away to some ethereal everywhere.

One vinyl clerk recently noted a trend that’s apparent across the country: “I was working at a record shop during the pandemic, and once we reopened, there was a whole new group of people who were like, ‘I just got turned on to records. I’m getting a soundsystem.’”

Powering up the DAC and hearing high-def streaming for the first time was, to a certain extent, akin to cleaning smudged eyeglasses to reveal a forgotten, longed-for vibrancy.

In his epic book Ocean of Sound: Aether Talk, Ambient Sound and Imaginary Worlds, writer and musician David Toop contemplated the secret realm that reverberating soundwaves can create, one which many of us now visit on a regular basis and as often as possible. He noted that “whether the echoes are synthetic or natural –– Jamaican dub, a North African call to dawn prayer shattering the early morning silence as it blasts out of a tower-mounted loudspeaker, Elvis Presley’s ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ or a Javanese gamelan recorded under the high roof of a royal palace –– there is no escaping their power to suggest actual, virtual and fantasy spaces.”

The post-punk band Mekons called it “that secret place that we all want to go: rock and roll.” David Berman of Purple Mountains described said “virtual and fantasy spaces” this way:

Songs build little rooms in time

And housed within the song’s design

Is the ghost the host has left behind

To greet and sweep the guest inside

Stoke the fire and sing his lines.

As long as you’ve got keys to the “rooms in time,” it makes little sense to reject non-analog sound signals that seek only to gratify you. And so-called “deep listening sessions” certainly don’t require primo turntables and cartridges, tube amps or $10k speakers to have an effect, though we’ll always argue that they can be remarkable enhancements.

Though I already had a decent vintage set-up before the pandemic, in the thick of it I decided to use some government money to buy said digital to analog converter (DAC). After doing a ton of research and reading countless reviews, I settled on a $200 DACMagic 100. At that point it was the only DAC I’d ever used, though I’ve since sampled a number of others at various listening sessions.

Powering up the DAC and hearing high-def streaming for the first time was, to a certain extent, akin to cleaning smudged eyeglasses to reveal a forgotten, longed-for vibrancy. Where formerly I’d outputted my Powerbook through a cheap digital-to-analog converter and plugged that via RCA jacks into an auxiliary input on my amplifier, the DACMagic spirited the digital signal of the Sun City Girls’ formerly tinny Torch of the Mystics stream past the laptop’s sound card, amplified, clarified, enhanced, beefed-up –– pick your steroid-suggestive verb –– the sound coming from Qobuz, Apple Music and Spotify to reveal recording depths otherwise only suggested. It was one of the best audio investments (about $200) I’ve made in years.

When, a few months ago, I raved about my DACMagic experience to Cambridge Audio’s Matt Reilly, he graciously offered to ship me the company’s luxurious DACMagic 200. Its main upgrade, among others, is a headphone jack that has enhanced my (Audio Technica) headphone experience just as the DACMagic 100 did with my vintage system (for reference, a Harman Kardon 730 twin powered amplifier and Large Advent speakers).

During our call, Reilly discussed the company’s range of offerings, all of which he described as meeting a current cultural desire to “get us back in touch with the magic within music.” He echoed that idea during a conversation with our friends at Aquarium Drunkard, describing “the escapism that can happen when you’re taken away to another time or memory by a melody. This can only happen when you fully embrace a song with no outside distractions. I imagine we will soon see lots of studies which show a ritualistic take of ‘quality sound’ as therapeutic exercise and a key well-being trend.”

It stands to reason, because the thrill of being carried away is that ultimately you end up in a kind of Utopia. Here’s Ryuichi Sakamoto talking to Toop about his version of this place:

“One of my friends, he’s a philosopher and critic. He made a word: outernationalism. Internationalism is still based on nationality. Being outernational is like Moses in the desert. There’s no country. There is just trade, transportation, communication and merchants, but there’s no nationality. It’s a utopia and I like it.” Though he forgot to mention art and/or music, he added, “I don’t want to be Japanese. I want to be a citizen of the world. It sounds very hippie but I like that.” During that time (the late ’80s or early ’90s), Sakamoto would include a then-new-fangled technology among his performance gear and send border-penetrating missives in real time.

Witnessing one of these concerts in the ’90s, Toop realized that “technology can reduce live performance to an anachronism. In the past decade, computers have delivered cybernetic music into realms which reach beyond human capabilities. For example, a concert stage in London: Ryuichi Sakamoto is faxing messages to friends around the globe during ‘Rap the World,’ a song in which machines do more of the work than the humans.”

(To riff on Toop’s thought, it’s not just technology that can upend live performance. A pandemic, we now understand, can also reduce live performance to an anachronism, or at least reconfigure it.)

To conclude on what may or may not be a non sequitur about the act of receiving clear messages from That Secret Place, Pauline Oliveros recalled the genesis of her phrase “deep listening” in Toop’s book, one that resonates on any number of levels when discussing the transformative nature of both recorded and live performance. She recalled in 1988 recording in a “big cistern” in order to release a compact disc of the music.

“When I was trying to write the liner notes, I was trying to come to some conclusion about what it was we were actually doing in there. The two words came together – deep listening – because it’s a very challenging space to create music in, when you have forty-five seconds reverberation coming back at you. The sound is so well mirrored, so to speak, that it’s hard to tell direct sound from the reflective sound.”

She continued of experiencing sound in a cistern, “It puts you in the deep listening space. You’re hearing the past, of sound that you made; you’re continuing it, possibly, so you’re right in the present, and you’re anticipating the future, which is coming at you from the past.”

May we all luxuriate such a heavenly place.

In Sheep’s Clothing is powered by its patrons. Become a supporter today and get access to exclusive playlists, events, merch, and vinyl via our Patreon page. Thank you for your continued support.