Good Smooth Jazz from Pat Metheny, 101 North (George Duke), Craig T. Cooper, Ben Tankard, and more! One of the most hated and controversial genres around, Smooth Jazz […]

The Colours of Eberhard Weber

In celebration of his 82nd birthday today, here is a retrospective on Eberhard Weber, the eminent bass innovator, ECM mainstay, and ISC favorite.

It’s hard to define the anomalous bass icon Eberhard Weber. He’s not necessarily a jazz bassist nor a classical composer per se, nor is he a flamboyant improviser regardless of how you classify his work. But one way to define him is by his sound. With innovations in bass design itself, Weber helped create electric instruments with extra strings, often fretless and upright, and used techniques found in modern classical to develop his own richly textured musical voice. With these skills, Weber has had a large hand in manufacturing ECM’s sonic identity.

Born in Stuttgart, Germany as the son of a music teacher, Weber was raised with classical music and training, which later shaped his compositional approach to structure. By the late 1960’s he had already collaborated with many of the best in Europe’s jazz scene and was considered among the continent’s finest bassists. It wasn’t until his solo recordings that his unique sound came to the forefront. Often showcasing his low-ranged slithery slides, and a technique of using contrasting ostinato patterns in different voices (a trick he had learned from Steve Reich), Weber applied it to his melancholic jazz context to uncover music that was uniquely Weber-ian. The brilliant Pat Methany in liner notes described Weber as “an individual who had a visionary sense of what music could be, totally of his own design.”

Since the 1970s Weber has released 15 studio albums and collaborated with many ECM-ers, including Jan Garbarek, Ralph Towner, Gary Burton, and Pat Metheny – and held a longstanding collaborative relationship with Kate Bush. In 2007, however, Weber suffered a severe stroke that put an end to his playing career – though not his musical activities. He continues to produce music by combining older session recordings with new keyboard treatments and overdubbing.

Like the man himself, Weber’s music is undefinable. Many critics at the time labeled his work “European Chamber Jazz.” Today it’s often called “ambient jazz,” and from a compositional perspective, his work could easily be filed in the “wavy modern classical” section if such a genre existed. However you label him, Weber occupies a sonic world of his own, creating visionary music rich in ethereal beauty and full of radiant colors.

Here are some of our favorites from the double bass maestro:

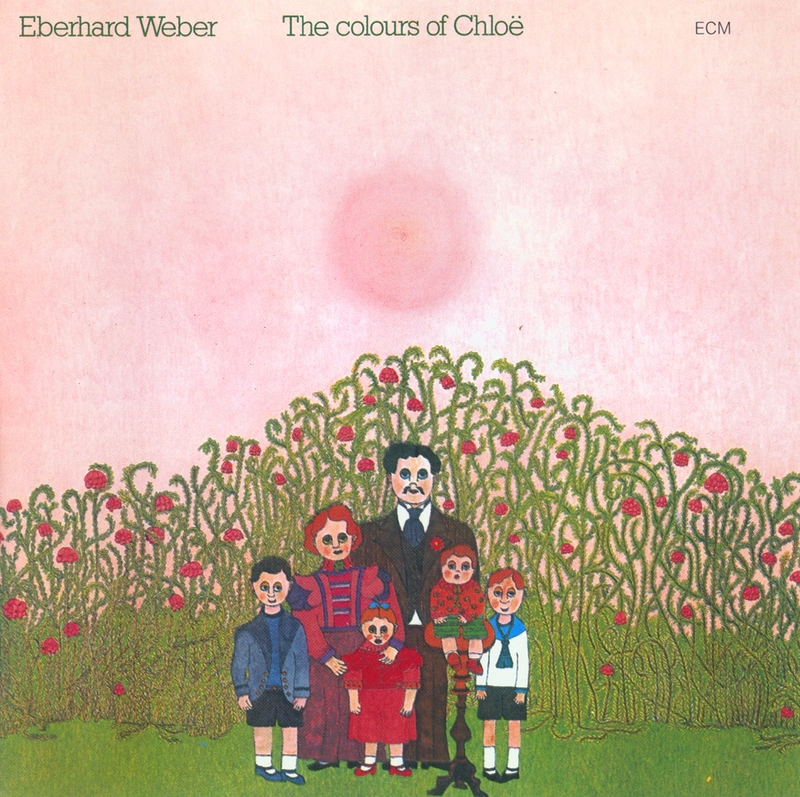

The Colours of Chloë (1974)

Weber’s bandleading debut, The Colours Of Chloë, showcases the upright bassist’s mastery of composition, space, ambience, emotion, and his instrument itself from the get-go. Paul Olson (allaboutjazz.com) called it “a near-perfect album by an artist whose creative vision seemed completely mature.” This is fusion in the fullest sense but, unlike most music in the genre, there’s no showboating here: Weber only takes the lead when the track calls for it. Describe it as “ambient jazz” if you want (there’s one YouTube video out there with that exact text), but there’s a beauty here that doesn’t require genre distinctions. Check the original review in our collection here.

Mal Waldron – The Call (1971)

Prior to his ECM debut, Weber paid his dues in the studio playing with many of jazz’s greats, from Baden Powell, Joe Pass, Dave Pike, Gary Burton and Wolfgang Dauner to this appearance on Mal Waldron’s little-known and sorely underrated fusion effort The Call. Composed of two captivating side-long jams, it’s incredible to hear Weber in one of his earliest recordings – and Waldron, for that matter – in a more late-night funk vein.

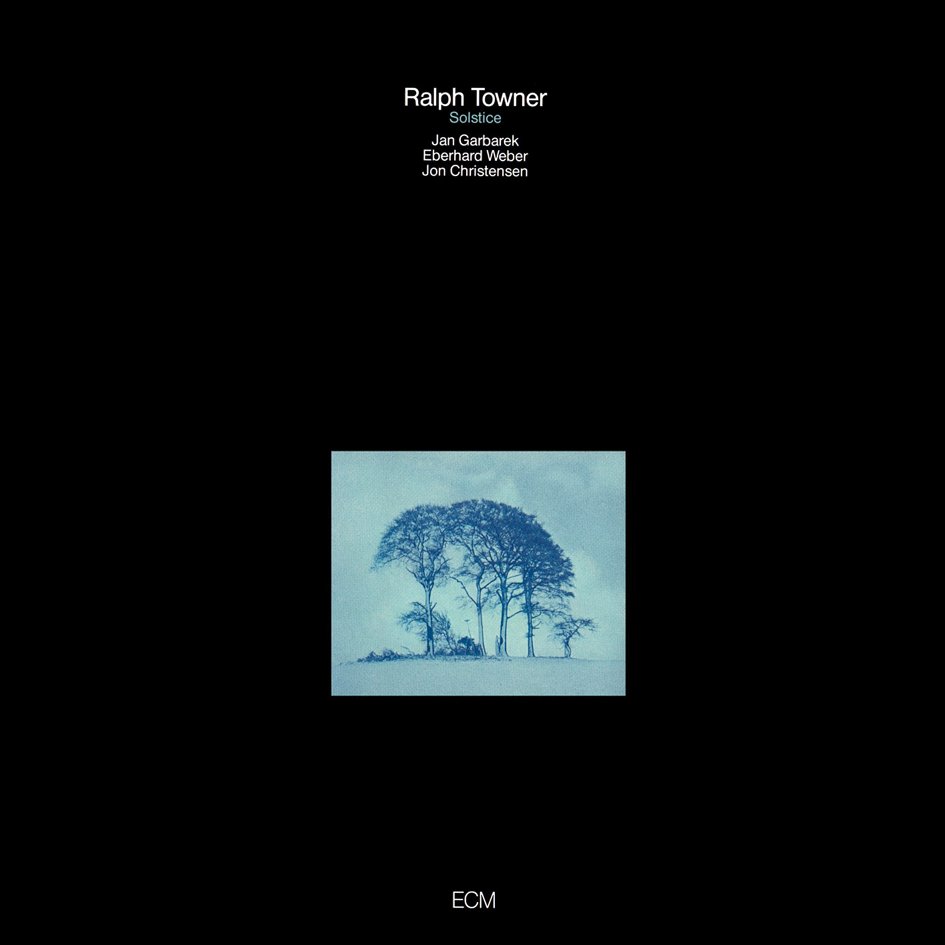

Ralph Towner – Solstice (1974)

Though Weber’s a sideman here, Ralph Towner’s The Solstice was a monumental piece and tidal-shifting moment for the sound of ECM and it’s players. The breadth of sound on this record is quite remarkable given that it’s just a quartet, as proven on Nimbus, one of Weber’s best known tunes.

Yellow Fields (1975)

Weber’s Colours follow-up band featured Charlie Mariano on saxophone, shehnai, nagaswaram; Rainer Brüninghaus on piano, synthesizer’ and Jon Christensen on percussion. The highly regarded jazz directory The Penguin Guide to Jazz considers Yellow Fields to be his best, writing, “Weber’s masterpiece is essentially a period piece which nevertheless still seems modern. The sound of it is almost absurdly opulent: bass passages and swimming keyboard textures that reverberate from the speakers, chords that seem to hum with huge overtones. The keyboard textures in particular are of a kind that will probably never be heard on record again.”

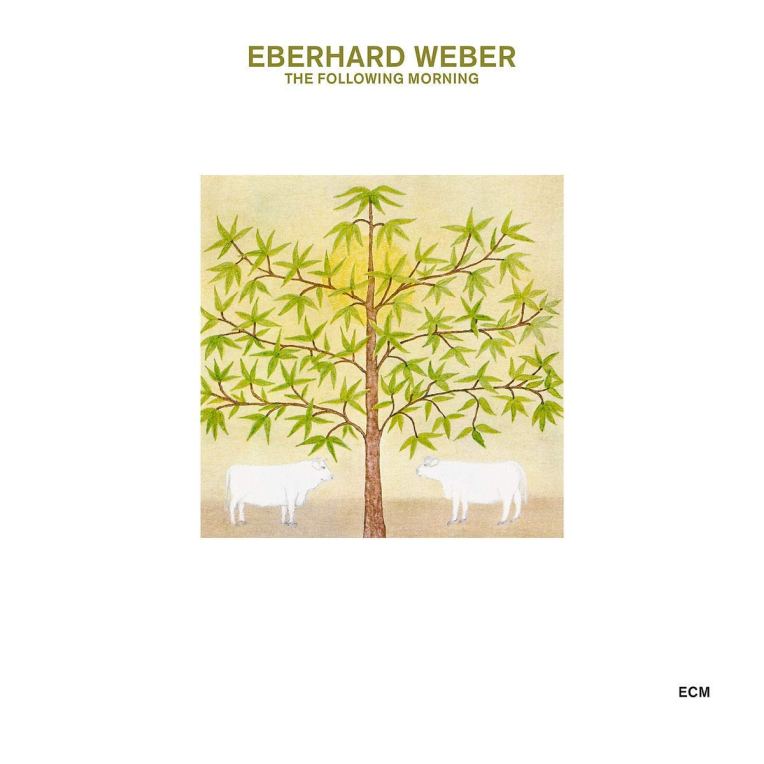

The Following Morning (1976)

On his third release, Weber eliminated drums and percussion in favor of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra. Minus a solid rhythmic drive, The Following Morning is Weber’s most “ambient” work. Contemplative and seemingly infinitely layered with tonal shades and shifts, the album is a highly recommended “deep listening” experience, whether the transportive opening notes of “T. On a White Horse” or the spacy cinematic close in “Moana ll.”

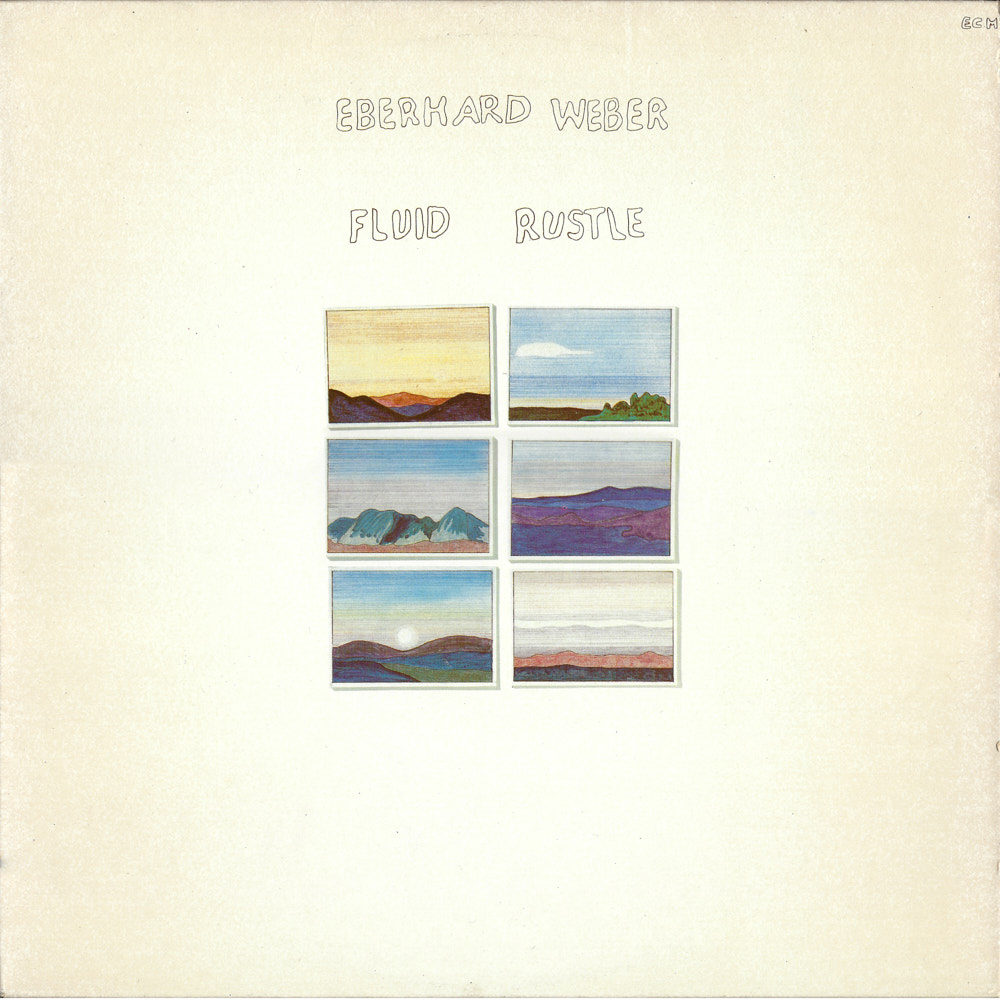

Fluid Rustle (1979)

If you visited our listening bar in the Arts District in the early daylight hours, there was a good chance you’d walk in to Fluid Rustle. Hands down the most played record in that room and remaining to this day our collective favorite, it’s the one that set it all off. Featuring a stellar lineup that includes Bill Frisell on guitar and balalaika, Gary Burton on vibes and marimba, and colored by the stunning euphoric harmonies of Bonnie Herman and Norma Winstone on vocals, Fluid Rustle is an indescribable masterpiece of ethereal beauty – and Weber at his most butterfly-wing delicate.

Pendelum (1993)

Pendulum is late-period Weber primarily playing solo bass with an echo effect unit, freeing the instrument to shine at its absolute best. Paul McCandless sprinkles some wind instruments here and there, but this is all Weber. Like Arthur Russell’s World of Echo, Weber’s approach in this beautiful stripped-down setting sounds as richly textured as his more collaborative recordings.

Kate Bush Collaborations

Finally, it’s worth noting Eberhard’s 30-plus-year musical partnership with Kate Bush, beginning with The Dreaming and across every subsequent album (minus The Red Shoes): Hounds Of Love, The Sensual World, Aerial, and Director’s Cut. This is their very first collaboration, “Houdini,” from 1982. Fun fact: Kate Bush got drunk – then downed a pint of milk and two chocolate bars – to achieve that gravelly, guttural vocal that appears throughout the song.