One of the scariest film scores ever was the product of a gift placed under a Christmas tree. “My father bought me a pair of bongos for Christmas […]

I Believe in Music: An Introduction to Ikutaro Kakehashi, Creator of Roland

A brief primer on Ikutaro Kakehashi, the revolutionary engineer who built the world’s most widely used electronic equipment.

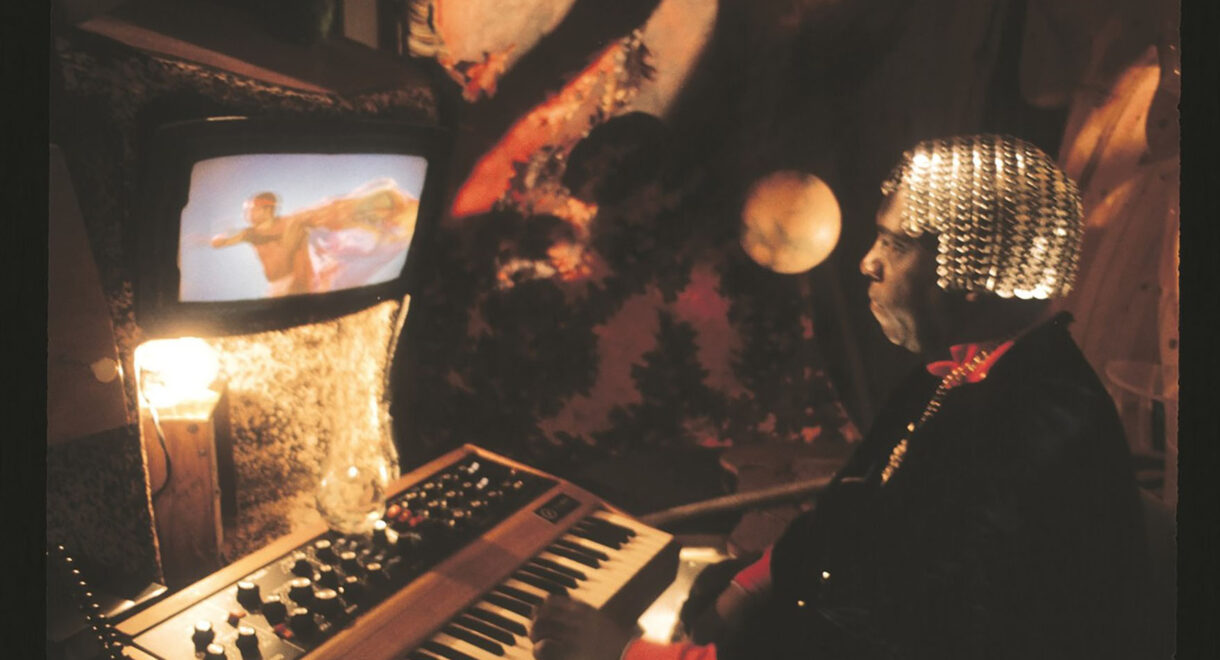

At 28, a young engineer named Ikutaro Kakehashi began a pursuit for innovative and affordable electronic musical instruments, machines that were accessible to amateurs and professionals alike. Simple, intuitive, easy to program but intricate and complex enough to produce magical futuristic sounds.

Ideally, what Kakehashi envisioned was something he — someone with absolutely no musical skills or training — could play himself . This ambitious goal led to a long life of discovery and, in his company Roland, iconic music-making machines. With these creations, whole new genres were born.

As is the unfortunate case with many of our deep dives into the lives of Japanese innovators, Kakehashi survived a harrowing past. Born in Osaka in 1930, both Kakehashi’s parents passed away when he was a child due to the 20th Century tuberculosis surge in Japan. His grandparents raised him, and while the city around him was experiencing a chaos of rapid industrialization, massive modernization and urbanization, “Taro” found solace in listening to his radio.

Music, and especially the little device that transmitted it, soon became his passion and drew him to engineering at a very young age. In his free time, he began building shortwave radios and repaired organs and watches. He had his own clock repair store at age 16. Soon after, Kakehashi would endure a series of traumas: his home was bombed during World War ll; he was rejected by universities due to “health grounds”; and, ultimately, he contracted the same disease that killed his parents.

The condition caused him to spend the next several years almost bed-ridden in a sanitarium. It was an unimaginably painful period, but he emerged from the experience with motivation and the decision to dedicate his life to music.

When we think of the innovators and architects of popular music, we tend to think of the faces, the stars on stage, the people on the album covers. But Kakehashi was responsible for the sounds, and laid the foundation for the artists to build on. Without him, who knows what hip-hop, techno, or any synthesizer-based music would sound like, or if it would even exist?

Below, we’ve shared some of Kakehashi’s most historic devices and innovations.

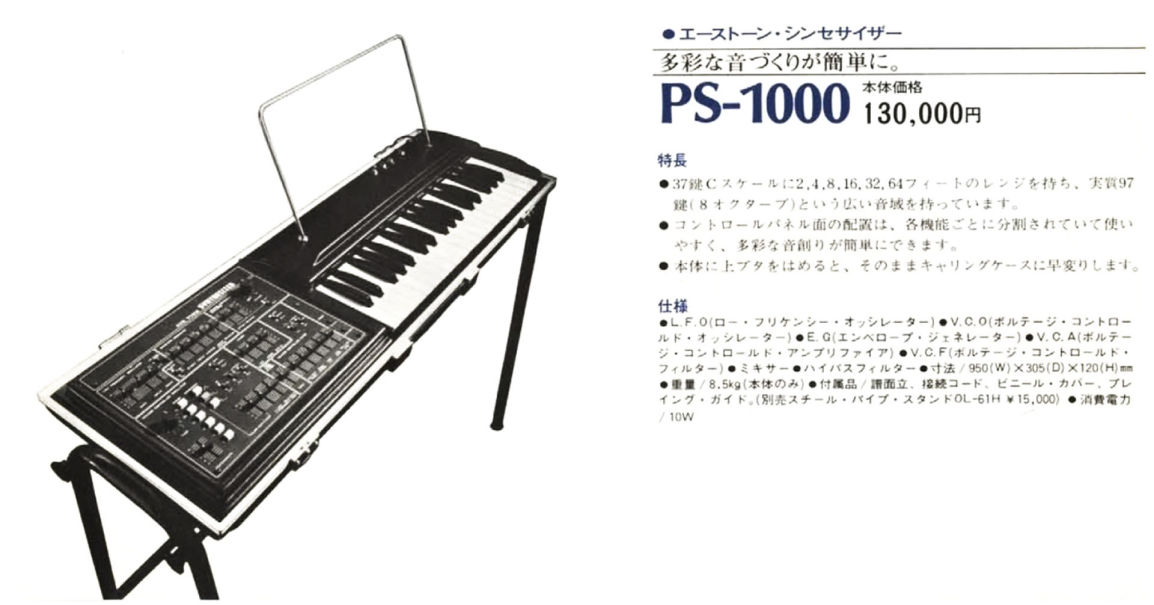

Ace Tone

In 1960, after making a few organ prototypes by hand, Kakehashi founded his first instrument manufacturer, Ace Electronic Industries. Many cite it as an early incarnation of Roland. Focused primarily on electronic organs and pianos, Ace soon expanded to effect units, amplifiers, a few monosynths and, eventually, early analog rhythm generators. These were precursors to the coveted drum boxes of Roland’s future.

If you trace it back, you can hear the roots of Roland’s futuristic tones start to form through these early 1960s models, with similarities primarily found with Roland’s CR-78. The most notable Ace-era Kakehashi products are the Rhythm Aces. The Ace Rhythm FR-1 introduced the world to the first transistorized drum machine and was the gateway box for Sly Stone before he graduated to the Maestro Rhythm King, AKA the “funk box.” The FR-1, which Hammond later picked up and implemented as a backing module in all its organs, also made history via Bee Gee Robin Gibb’s 1970 hit single “Saved by the Bell.” The first major pop song to utilize a drum machine instead of live drums, it was made possible by the FR-1’s “Slow Rock” preset.

Roland

After Ace Tone’s success and its introduction of early electronic drums and synthesizers, Kakehashi created Roland in Osaka in 1972, launching it with its first product, the TR-77. The TR series (TR standing for his established “Transistor Rhythm”) would lead to the development of the undisputed greatest drum machines of all time.

As forms of electronic music became widespread, these grid-programmed drum boxes found enthusiastic users and spawned entirely new genres. Hip-hop, house, techno, chillwave and synth-pop all owe huge debts to these now almost unattainable Roland devices. The 808, specifically, is the holy grail, an instrument that has influenced so much of music’s past, present and future.

The 808 was given the complete documentary feature treatment in 2015, which we highly recommend, but where it all began for this iconic 1980 instrument, the “big bang” so-to-speak, was Afrika Bambaata and the Soul Sonic Force’s 1982 hit “Planet Rock.” Only 12,000 were ever made and the 808 was discontinued in 1983. But they eventually found their way into the hands of artists who would use it in service of an endless amount of 80’s greatest hits, from Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing” to the Beastie Boys’ “Paul Revere.”

Back then, drum machines and synthesizers, in general, were made to replicate live instruments, but the 808 was made with transistors that made them sound different by modulating the drum sounds they were originally programmed to “replicate.” Kicks, snares, and hi-hats, as a result, feel not quite like the real thing. Instead, the waves come out sounding completely, well, electronic.

It’s difficult to fathom how many revolutionary Roland products were made in the 1980s. The entire company could be satisfied with the legacy that is the 808. But three years later, they dropped a sequel: the TR-909. First released in 1983, the 909 has powered more house and techno tracks than you can name and can easily be dubbed the key ingredient in the genesis of electronic dance music.

Roland’s website describes the design process like this: “For the TR-909, Roland was still pursuing the idea of an analog ‘drum synthesizer’ rather than a machine that played back digital samples of ‘real’ drums. The analog approach gave the user extensive control over the sound — for example, you could de-tune the kick drum or toms for some very creative results. But it was decided that the hi-hats and cymbals of the TR-909 should be digital recordings of their acoustic counterparts, as the engineers felt a more realistic sound would help the TR-909 feel like a substantial upgrade compared to the all-analog TR-808.”

Under Kakehashi’s leadership, not only did Roland make now-essential drum machines but pioneered synthesizer technology. He introduced the first compact synthesizer in 1973, the SH-1000, and spent the next two decades creating future classics.

In 1981, Kakehashi released the flagship and pinnacle of Roland synthesizer engineering, the Jupiter-8. A robust eight-voice polysynth with deep programming abilities that Kakehashi would use as a blueprint for more affordable future models, it was the ancestor of all Jupiter and Junos. These iconic feature-rich synths would cement the sound of the ’80s, from pop hits by Madonna and the Pet Shop Boys to the lush underground club sounds of house pioneer Larry Heard.

Complete in-depth literature could be written about any one of the Juno and Jupiter models, but some other noteworthy Roland classics to celebrate are the JD-800, an ambient and new age staple; the TB-303, a rubbery bassline sequencer synonymous with the acid house sound; and the SH-101, a monosynth heavily used in dance music that’s great for bass and lead lines.

Here’s a fun video of A Guy Called Gerald playing all Roland gear at a pool party. Featuring those mentioned above: A 909, an 808, a Juno 106, two SH-101’s(!), and a 727.

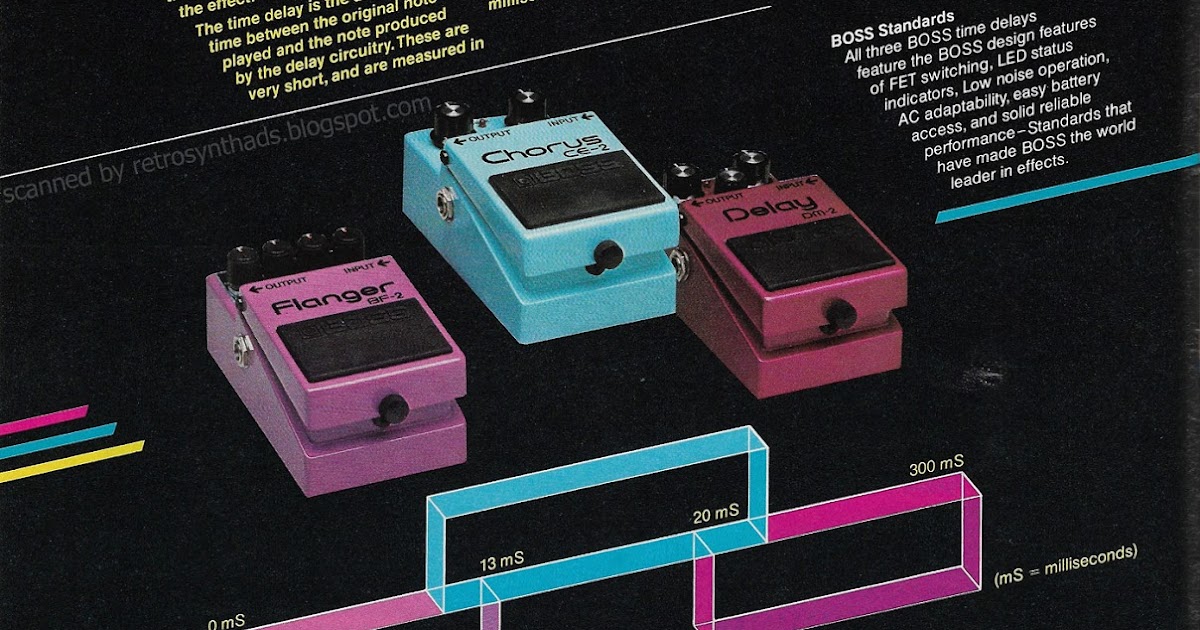

Boss / Effects

Although Kakehashi might be remembered more for his 80s synths and drums, he also significantly impacted rock music in the 1970s. Ikutaro was at his core a music lover and often traveled to the UK in the early 70s to witness the classic rock explosion.

While there, he gained respect for the UK’s creative engineering for amplifiers and effects and was often found frequenting London music shops to test out new gear. He founded Boss in 1973, and it soon became the gold standard for guitar effects. The company created classic pedals for guitar and bass, including the CE2 Chorus pedal, the DD3 digital delay and the DS-1 Distortion box.

There’s a lot more to mention here in terms of Roland and effects units, like the iconic RE-201 Space Echo, but we’ll leave that for another piece.

MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface)

The growth of electronic music would also reveal a significant weakness in producing it: communication. It’s hard imagining what a world without MIDI would be like, but that was the reality in the early 1980s. There were no standardized means of syncing instruments by different companies.

Kakehashi saw this as a massive roadblock in the growth of electronic devices, so in 1983 he and Dave Smith of Sequential Circuits proposed an industry standard. Kakehashi solicited the Japanese companies Yamaha, Korg and Kawai while Smith handled the American producers Moog, Oberheim, etc. Initially received with a lot of opposition, a standard was eventually agreed upon.

The announcement was made by Robert Moog in the 1982 edition of Keyboard Magazine. Using Roland’s DCB early sync technology as a basis (Digital Control Bus), Smith and Kakehashi devised a universal interface to allow communication between any piece of electronic equipment.

In the words of Perfect Circuit, the event was “an unprecedented act of bipartisan collaboration between competitors [that] heralded perhaps the most important musical technology of the century: a common language available for all electronic instrument developers.” The revolutionary sync capability opened the floodgates for electronic music, earned Kakehashi and Smith a Technical Grammy award, and to this day remains the industry standard.