In conversation with Small Medium Large, a new quintet from the burgeoning new West Coast jazz & improvised music scene. In 2018, LA-based jazz and post-rock guitarist Jeff […]

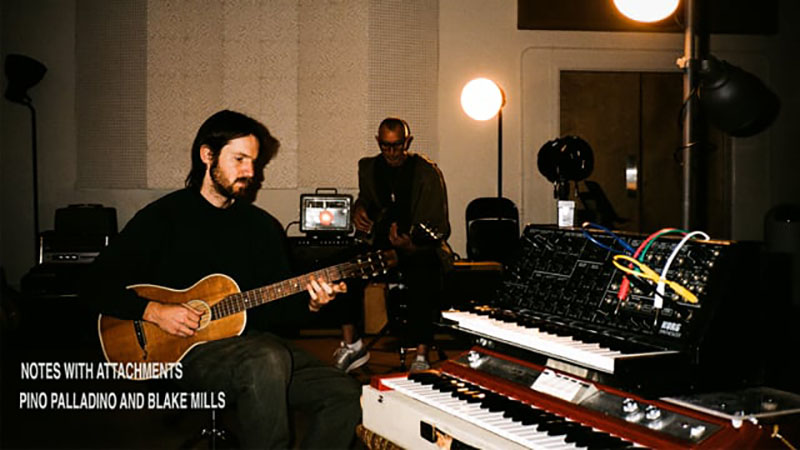

In Conversation w/ Pino Palladino, Blake Mills, Sam Gendel

Pino, Blake, and Sam’s ‘Live at Sound City’ is out today via ISC Hi-Fi Selects.

Generations apart, Pino Palladino, Blake Mills, and Sam Gendel are in many ways an unlikely trio. Palladino came up in the early ‘80s as a studio musician and earned worldwide acclaim in 2000 for his work on D’Angelo’s Voodoo. Mills received multiple Producer of the Year Grammy nominations in the 2010’s for his work with Alabama Shakes, John Legend, Laura Marling, and Perfume Genius. Gendel’s critically lauded Music For Saxofone & Bass Guitar landed just a few years ago on LA-based experimental all-genre imprint Leaving Records.

In 2018, the trio came together live for the first time to play one of the only shows at the In Sheep’s Clothing hi-fi bar. It was an intimate affair with clear chemistry among the three musicians. Three years, one pandemic, and countless studio sessions later, Palladino would release his first ever solo album Notes with Attachments in collaboration with Blake Mills featuring Sam Gendel on saxophone.

Today, In Sheep’s Clothing is proud to continue the story with the release of Live at Sound City. In anticipation of the release, ISC’s Editor-in-Chief Phil Cho spoke to Palladino, Mills, and Gendel about their inspirations, playing as a trio, and the influence of Sound City studios on the record.

Musicians always talk about discovering their voice on the instrument. Pino, people know your voice on the bass, but what was the process like finding your voice as a songwriter?

Pino: I guess I’ve got a lot of different styles as a writer. This album developed through the course of working with Blake and realizing some of my ideas. The compositions evolved through that process. Each song has a different identity, so there’s no kind of recognizable sound from track to track and that was very enjoyable for me.

I heard this album was developed over twenty years. Do you feel like you were pulling bits and pieces of your whole musical story to form this album?

Pino: Definitely. At least a percentage of it anyway. Probably like 15 or 20 % of all the stuff that I like. Maybe more. I guess the ideas that resonated with myself and Blake are the ones that you hear on the album. There’s of course other directions I like as well…

West African, Cuban, jazz, funk, and folk have all been mentioned as influences. Were there specific records or artists you shared with each other during the writing process?

Blake: I don’t remember us ever talking about what kind of record it could be based on other artists, but I think we might’ve had certain musicians in mind to play on it. This was an opportunity for me to introduce Pino to Sam. I think the first time I got to play with Pino was also the first time I got to play with drummer Chris Dave. Pino sort of opened my world to what he could do. There were instances where we would talk about songs with the excitement of who we could have play on them.

For me, that was a huge thing just hearing Sam’s interpretation of some of the tunes. All of a sudden I realized, “Wow, this music can exist live.”

pino PALLADINO

There are quite a few pieces of interesting gear used on the record, like the Magnatone Hurricane bass. The instruments feel like a key part of the story here. How did you choose which instruments to use on the album?

Pino: The Magnatone Hurricane bass was an instrument I had always been looking for. My friend in Japan had one and long story short he wouldn’t sell it, but I eventually found one. I was really pleased to find that it had an adjustable damper where the bridge is. I was listening to a lot of West African music at the time and experimented with trying to make the Magnatone sound like a ngoni or a djurkel. It was fun to make a sound that didn’t sound like a regular bass guitar.

I also see that in the credits there’s listed “Gamelan Fretless Bass.” I googled that and nothing came up. What’s the story behind that?

Blake: A lot of the documentation of the instruments on the back of the record was a response to the music sounding almost like a big band composition. Sometimes we’d be working and then we’d add a part, then another part, and it would become this orchestrated thing. When you just have two guitar players there’s a lot of redundancy sonically if you just keep putting those parts on stringed instruments. It forces you to get a little inventive and playful in the same way somebody might do a prepared piano by putting paper clips or cotton balls in there. There were things that we’d do to guitars and basses to try to get them out of the palette of the instrument. This was before we had Larry, Sam, and other people bringing in other instruments. We were kind of trying to cover as much ground as we could on our own.

Pino: The gamelan thing you mentioned was Blake and I both playing fretless instruments more percussively with short notes and slides. Blake actually came up with that name to describe the sound.

There seems to be so many complex, layered elements on the album version. How did you break all that down to be played live as a trio?

Blake: I remember us getting together and having the record playing through some PA speakers. (engineer) Joseph Lorge was in the control room with the sessions open. He’d hit play, we’d be listening, then we’d tell him to stop and solo certain parts so we could identify what we were doing. More than anything, it was just to refresh our memories on how the different parts lined up.

There was a sense of the composition within all the layers. At the end of the day, you’re left with this thing that’s pretty meticulously crafted and orchestrated. The sense of the composition comes from all of those things together, it’s not just the one melody anymore. In some cases, it was about trying to figure out if we needed to represent the totality of the song, or if there’s something cool about going back down to just the element we wrote this from and then finding a new instrumentation around that with just the trio.

Pino: I think Sam’s role in the live performance really enabled Blake and myself to take a step back. Sam gave us such beautiful harmonic beds to work with that filled out the sound to such a degree. For me, that was a huge thing just hearing Sam’s interpretation of some of the tunes. All of a sudden I realized, “Wow, this music can exist live.”

How was this process for you, Sam? Hearing the music as a whole and then re-interpreting those parts?

Sam: I feel like we’re still working on it even now. It’s kind of a living thing. It keeps evolving because there are so many handoffs between everyone. Usually everyone is doing two things at once, but the two things can be referenced back to the original music from a totally different place. I’ll hear some drum part and then I’ll want to dip into that on the sax. Pino might be thinking melody. The fun part is bringing all these uncommon flavors together.

Blake: There was a thing that happened on Instagram around the time the record came out. Someone posted a video of them playing the guitar and the bassline to “Just Wrong” together in one part. If you watch the live video, it’s not how I ever played the guitar part. The part I’m doing is just the chords with Pino doing the main melody. Somebody must’ve thought that it was all in one thing, or just figured that’s the composition or how the song is played. Another person replied with their own video and it became this sort of thing on Instagram where people were learning how to play their own interpretation of the song. It’s actually really similar to what we’re doing with our own record. We’re just listening back for ways of combining different elements into different instruments and roles. It’s fascinating.

Together it forms “the thing” instead of forcing it through these linear hierarchical formats that you’d expect from even just that specific instrumentation. It’s all flipped upside down.

SAM GENDEL

Listening to the record with your eyes closed is interesting in that way. You can almost imagine it being six or ten players versus just three like you see in the video.

Pino: I would say listening to the live version without the video is such a different experience. You don’t know who is doing what or what each instrument is doing. It actually sounds bigger to me just listening to the record versus watching the video. It works great as just audio.

Groove is obviously a huge part of the group’s sound. Compared to the album, there’s no drummer on Live at Sound City. Can you speak a bit on the groove as a trio versus a full group?

Pino: I think the groove doesn’t have to be stated, but you feel it. Working as a trio, we’re all aware of the individual pulse of each song, but it’s not necessarily stated in an obvious way. That was the fun part trying to find a way for it to be grooving, but the groove isn’t stated in the way of a backbeat, or a bass drum figure, a hi-hat or whatever. I think that’s something we all felt which is why it works as just three people.

Blake: I think each one of us plays in such a way where the listener starts to imagine the pulse. Then there’s this fun game going on where on every bar or beat the listener gets to see how close they are to our internal, unspoken groove. It’s almost like telepathy between the band and the audience.

Pino: It’s different. It’s really fun now because Abe Rounds has joined us to make it a quartet. Even though he’s providing beats, it’s still not overstated. It’s left quite ambiguous, and that’s the beautiful part of what we do.

Sam: Everyone is contributing equally to a sort of circle. Everyone is always providing ever-shifting information from their instrument that contributes to all the aspects of the music. Together it forms “the thing” instead of forcing it through these linear hierarchical formats that you’d expect from even just that specific instrumentation. It’s all flipped upside down. Together it creates the whole picture.

Pino: That’s the challenge that we enjoy when we all play together. It’s changing in microseconds. You just react to something you hear. If you feel something to make that groove a little stronger, you just do it. We all trust each other to make the music work.

I think all of us are also people who have a pretty healthy dissatisfaction with the sounds of our own instruments and how they’re typically used.

BLAKE MILLS

You all have such unique approaches to your instruments. Are there techniques, methods, ideas that you’ve picked up from each other that you’ve applied to your individual playing?

Blake: I’ve probably learned and stolen more from Sam and Pino in the last three years than anybody I’ve heard or played with before. In record making and producing, I’m so used to being the one who’s meticulously scrutinizing the groove and how things are playing together. I’ve never experienced someone with as sensitive an ear to timing as Pino. It’s just on another level the relationship he has to the kick drum and the snare and how he can hear where his notes are falling and stopping. That transcends beyond bass into just the way everything is playing together.

Sometimes we’d be working on a song with 30 different instruments playing and he’s hearing this one thing. Sometimes people can trip in the studio and fixate on some little detail. I learned really quickly that’s never what’s happening with Pino. He’s always hearing something in there that could be better.

Pino: Yeah, I think all three of us are pretty ill. It’s OCD and then some. We can get so tuned in to tiny details. It’s a good illness.

Sam: Pino, you got that crazy feel man.

Pino: Yeah I don’t know. It’s hard for me to be able to hear things as other people hear them. It’s always a challenge.

Blake: I think all of us are also people who have a pretty healthy dissatisfaction with the sounds of our own instruments and how they’re typically used. Sometimes we have a little envy for other timbres and other instruments. With Sam’s playing, he was somebody who I immediately recognized had that kindred sort of cynicism, but with a really imaginative approach to an instrument you’ve heard a million times. That’s something I’m constantly inspired by: The ways in which he circumvents what the wind instrument is supposed to do. He creates something that’s purely imaginative and spontaneous. It makes me excited to go back and approach my own playing that way.

Sam: Pretty much every time I’ve showed up at Blake’s studio, we’ve never recorded something the same way twice. Even if it’s the same instrument across multiple meetups. He’s never treating something from a formulaic place. Once I experienced that with Blake, it got me to throw out so much in my brain and just start approaching playing music from that place every time. Just being present and allowing yourself to follow instinct. Not everyone is that courageous, and that’s something that’s transformed my entire vibe ever since.

With Pino, I’ve listened to so much of his playing for so long that I feel like it’s deeply informed my sense of music through time. It’s just his sense of sound in time with other sounds, how they interact, and the feeling that can evoke in a person emotionally. You can take it technically, but it’s really just an emotional thing. Pino is such an emotional, soulful musician.

Pino: Just being around Blake and Sam in the studio and hearing them play my songs is just a dream. I couldn’t be happier.

There’s a song on the album called “Man from Molise” where my original version was so different to the one that ended up on the album. Blake’s response to the original idea was so interesting. He said “how about we slow this down?” We actually ended up slowing it down to half speed. It was such a radical thing for me. I was open to it, but I didn’t expect it to work. That sort of openness to taking a tune in a different direction both harmonically and rhythmically has been really impactful.

With Sam, I sort of don’t even think about other saxophone players anymore. I just think, “I want Sam.” He provides “that spot” with his approach to harmony. The choices that he makes always make me smile.

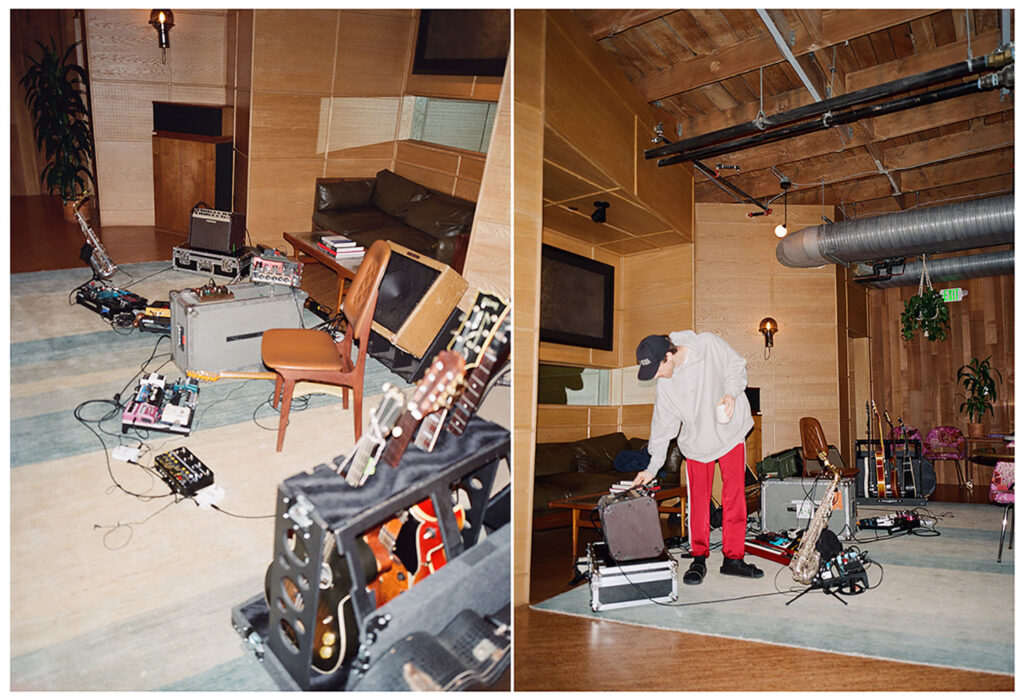

Sound City obviously has a very storied history and place in music and this EP is aptly titled “Live at Sound City.” What’s special about this place and how did the studio contribute to the recording?

Blake: Sound City has been my home base for almost five years now. When I moved into the building, it was right around the time when Pino and I were starting to work on the first songs on the album. Learning and experimenting in the studio went hand-in-hand with discovering the music together. In a lot of ways, they informed each other. A lot of the sounds on the record were the result of discovery in a new space. There’s some magic going on and beginner’s luck.

The feeling of Sound City being a clubhouse with a sort of open door policy makes it a good place for us to go and be vulnerable and experiment. Half the time we don’t expect it to work, but it’s worth exploring and imagining.

Pino: Sound City is definitely our base camp. It feels very comfortable, like you can suggest any idea, try anything, go down any rabbit hole and find a way out. It gives you that secure feeling.

The hi-fi community loves Notes with Attachments. I remember even seeing Klipsch post it. For each of you, what’s your listening practice at home? Is hi-fi or deep listening a consideration?

Blake: I fantasize about that kind of setup. The control room at Sound City is where I do most of my listening. The setup there is the George Augspurger designed speakers as the mains and the classic NS-10 studio monitors. That’s our “hi-fi setup.”

Pino: Same for me. Sound City is my home camp for listening to music. That’s my ideal environment – those big speakers in the control room.

Sam: I got this little cassette boombox at home. I love it. There’s something special about it. It’s actually my preferred way of listening to music.

Join us in-store tonight March 25th to celebrate the release: https://insheepsclothinghifi.com/event/ischfs-001-record-release-party/

Purchase the album in our webstore: https://insheepsclothinghifi.com/product/pino-palladino-blake-mills-sam-gendel-live-at-sound-city-ep/