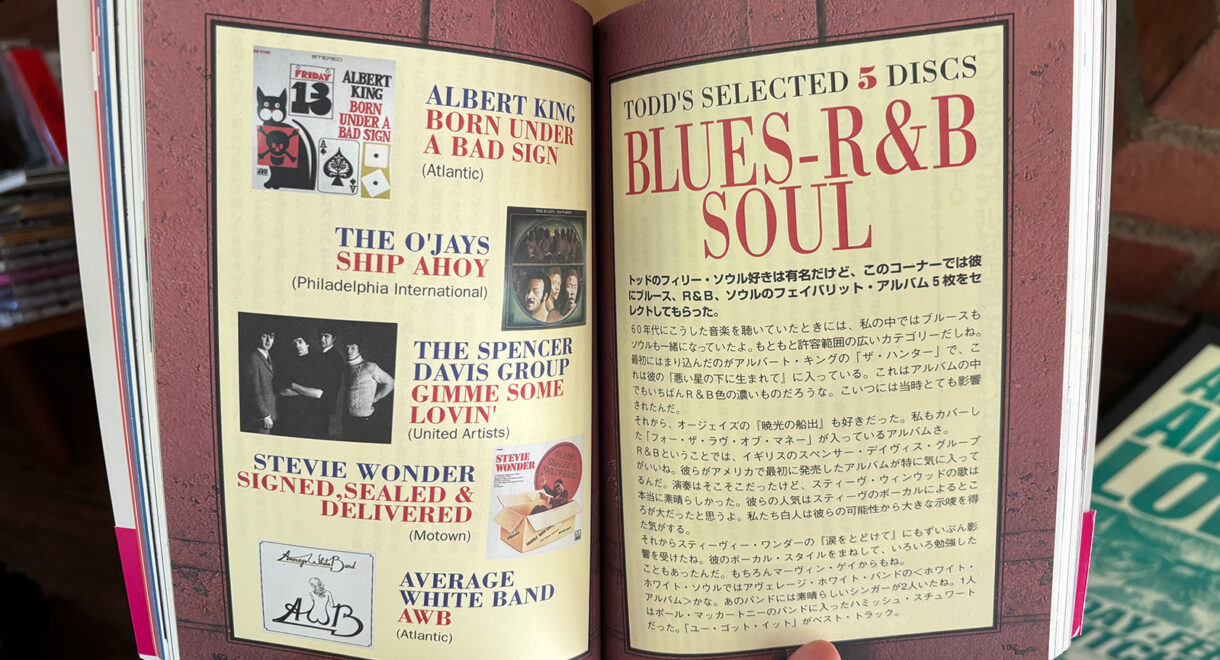

“Dubwise but not exactly dub, rich in ambience but not exactly ambient music.” With three of the classic Sade albums (Promise, Diamond Life, Stronger Than Pride) recently repressed […]

Celebrating the Luther Thomas Human Arts Ensemble’s Essential 1973 document ‘Funky Donkey’

A new reissue by Wewantsounds brings back a raucous free jazz, soul funk session recorded in an empty St. Louis sanctuary.

In 1973, the late alto saxophonist Luther Thomas convened eleven players to record a funk/jazz free-for-all at a mostly empty Berea Presbyterian Church in the Laclede Towne neighborhood of St. Louis. The 1977 record that came out of that session was called Funky Donkey. Two side-length pieces of structured, percussion- and brass-driven improvisations, it hits like spiritual spontaneous combustion.

The consistently spot-on Paris-based label Wewantsounds just reissued the album, originally released on Thomas’s private press label Creative Consciousness Records, in conjunction with the respected Chicago gallery-label Corbett vs. Dempsey. It’s the first vinyl pressing of the album since it originally came out.

Funky Donkey was reissued on CD in 1999 by Chicago’s Atavistic label and their Unheard Music Series, curated by John Corbett. The brilliant curator, collector and label head formed Corbett vs. Dempsey in 2006 and has supported the city’s scene for more than 40 years.

Before cofounding that imprint, the Unheard Music Series was a crucial bridge connecting listeners with obscure new and old music in the pre-streaming, pre-YouTube 1990s, and issued recordings by, among others, Peter Brötzmann, Fred Anderson, the Rova Saxophone Quartet and Joe McPhee. As a young would-be music writer, I actually wrote a feature about Funky Donkey when that Atavistic/UMS reissue came out, and some of that story has been adapted for this.

Corbett told me back in the day that the impetus for the Donkey reissues was a chance encounter with some works in his collection. “I had a copy of the record and had sort of been looking through my collection, wondering, ‘What’s next? What are we going to work on?’ I’d always loved this record, and I stumbled across it in my collection, and I thought, ‘It would be fantastic to do this.'” After tracking down Thomas, who, though from St. Louis, divided his time between New York City and Copenhagen, Denmark, Corbett received the masters in the mail.

On Funky Donkey you can hear eleven St. Louis musicians overwhelm both a tape deck and a church with a remarkably intense, riff-heavy blend of free jazz and funk. Think Pharoah Sanders’ gutbucket version of “Love Will Find a Way” from the recently reissued 1977 record Pharoah.

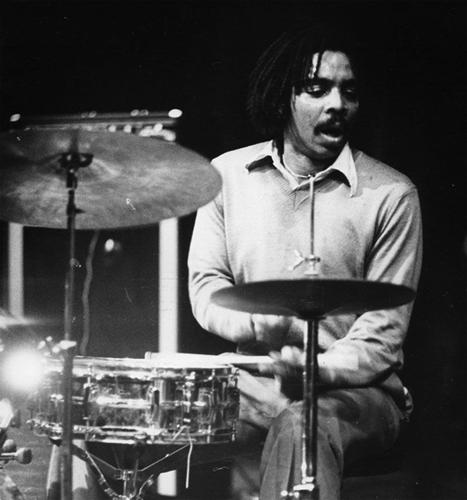

The session’s musicians were not only aces in the area (many were members of the legendary Black Artists Group, the jazz musicians’ collective) but also some of the most original voices of the international jazz scene at the time: Thomas (alto saxophone), Lester Bowie (trumpet), Joseph Bowie (trombone), Charles “Bobo” Shaw (trap drums) and J.D. Parran (reeds), along with Floyd LeFlore (trumpet), Harold “Pudgey” Atterbury (trumpet), Abdella Ya Kum (percussion), Rocky Washington (percussion), Marvin Horne (guitar) and Eric Foreman (Fender bass).

If you’re counting at home, that’s three drummers, five brass players, a reed player and a bassist. The group members’ credits over the years are something to behold, including the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Defunkt, World Saxophone Quartet, Stevie Wonder, AACM, Anthony Braxton, and the Contortions.

The title track begins with a moan from Thomas’ alto, a wobbly clarion call that indicates no direction but out, making you wonder where they’re headed. Where they’re headed doesn’t seem to be, judging from this little cry, into the funk, but within moments a messy horn section — the Bowie brothers’ trumpet-and-trombone attack, along with the two other trumpets — crashes smack-dab into a pure-funk guitar riff spit out by Horne that sounds like a drunken Meters outtake, and immediately the 11 are deep in the funk. They’re riffing heavy, and although the players are ensconced in jazz, they’re also revealing their collective roots in St. Louis’ blues and rhythm & blues scenes. The sound is huge, and you can hear the echo of the cavernous Berea Presbyterian Church, which, at the time, was a Movement church that doubled as an arts center.

“I remember it quite well,” Parran told me when the Atavistic reissue came out, of the performance. “My mama came! [Laughs.] I felt so sorry for her. She came in the door and Bobo and them were mashing — and you know how loud those churches are. I don’t see how my mama took it, the volume alone. She acted like — she didn’t let on that there was anything funny about it. I thought, ‘How is she going to take it?’ The volume alone was so great. I just said, ‘Damn!’

“I don’t remember there being hardly anyone there other than my mama,” he laughs. “I think there was more cats onstage.”

That title track burns; that riff continues unabated for eight glorious minutes, building up a wild momentum that seamlessly melds the freedom of BAG improv with the sturdiness of James Brown funk. Then, out of nowhere, all hell breaks loose as the musicians descend into the improvisational abyss, and a (relative) silence ensues. All 11 players are examining, blowing, respecting; guitarist Horne somehow lands on Howlin’ Wolf’s evil “Killing Floor” riff, which drummer Shaw latches onto immediately and pounds into the ground. Solos are taken, and the whole thing, all 18 minutes of it, is over as quickly as it’s started.

What’s most surprising about the document is the funk. The record stomps, and those familiar with BAG’s output will be surprised at the solid structure within “Funky Donkey.” Parran said that this was the direct result of the influence of Miles Davis. “Miles didn’t just influence the people that were playing the trumpet. He kept influencing so much what kind of music they actually played. Miles had taken over everybody’s consciousness at that time. Bobo and them, they — this was a funk record.

“We were all pretty much steeped in the funk tradition anyway,” he added. “Some of the guys grew up playing with Little Milton, as well as, of course, Albert King, Ike and, of course, Oliver Sain. We were pretty much steeped in the blues. We were getting our early experience in the blues and rhythm & blues. But this funk thing was different, the way Miles put it out there. It was extended performances; it wasn’t vocally oriented, you weren’t backing up singers per se, and the instrumentals were right out there. It was basically coming in with a free form — those guys had some [riffs] they knew, but they didn’t make a big deal out of it. You just came in and played. It was fairly free-form.”

Free-form it obviously is, but it’s free-form coming out of the imaginations of artists at their peak. You can hear it on the second track (side two of the original release), “Una New York.” It’s a more restrained examination of a song written by Shaw, and it illustrates the depth of feeling within the collective. Lester Bowie tosses off a Mexican trumpet line that seems stolen straight from a spaghetti Western, echoed in spirit by guitarist Horne. They uncover another riff, this one less raucous, more restrained — though containing enough energy to power a 747 — that they proceed to celebrate for another 18 minutes. Lester in particular is highlighted here, and the listener is treated to remarkable glimpse of a master.

Says Parran: “The stature of the band — Lester Bowie was no small potatoes, even in ’73. He had already come back from Europe and had appeared on the cover of Downbeat magazine along with Don Ellis and Freddie Hubbard. Lester Bowie had made it, and he was on the gig, so it was no little deal.”

Corbett called it “this important part of the puzzle that’s all but forgotten and rarely mentioned, even by the people who were there. The World Saxophone Quartet guys rarely mention it; my experience is that they never really talk up the BAG heritage that much.”

More information on Funky Donkey can be found at We Want Sounds.