A fresh look at the 1999 book that traced Detroit techno from Belleville basements to Berlin dance floors and the artists who carried it there. Looking to add […]

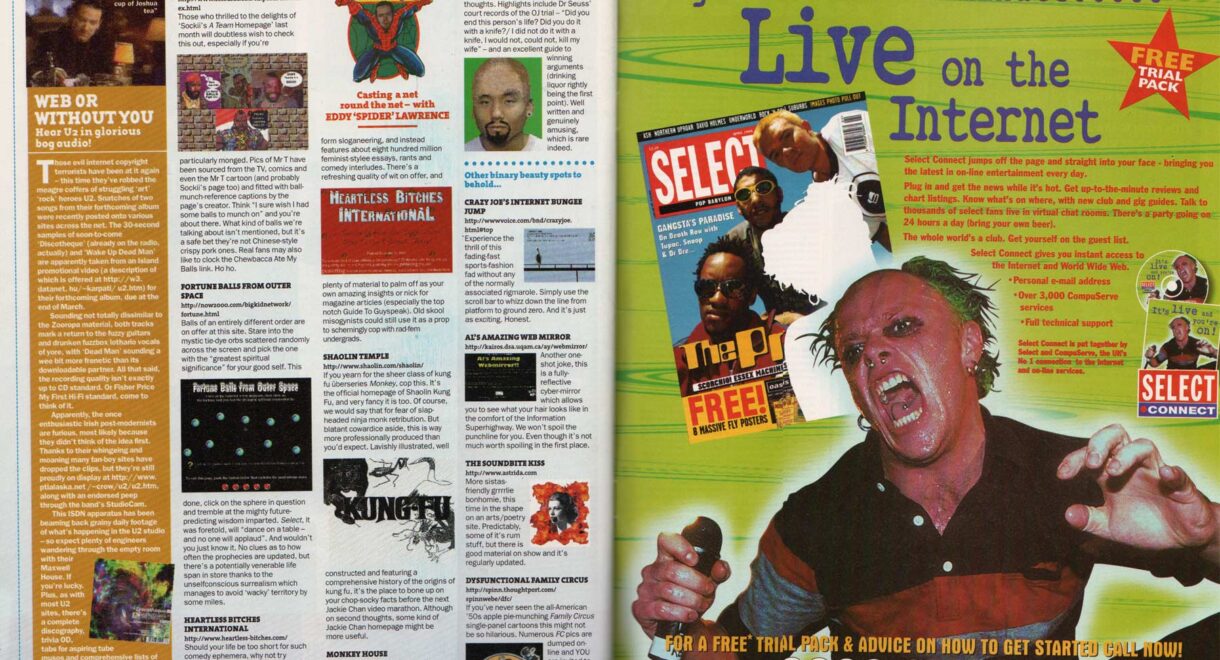

The Sound Projector: Experimental Music Meets Underground Design

The magazine’s bold layouts, illustrations and collage were as radical as the music it covered.

The Sound Projector is one of the strangest and most exhilarating music magazines to come out of Britain in the 1990s. Edited by cartoonist and ResonanceFM broadcaster Ed Pinsent, it first appeared in 1996 and ran like a stubborn beacon for nearly two decades. Its pages are unmistakable: hand-drawn headings, oddball cartoons, bold, in-your-face type.

Where other magazines lean on authority or scene reporting, The Sound Projector focused on obsession and personality. It reads like a diary of obsession, a listening journal disguised as a magazine. Decades after it first published, it remains a brilliant consumer guide. Although it hasn’t issued a new issue one since 2022, Pinsent remains a force who has maintained a radio show for more than two decades.

In its first issue, Pinsent made the mission clear. “Put it down now if all you want is obsessive trainspotter information, or 100% authentic facts,” he wrote. Instead, the magazine promised to be “personal, speculative, humourous, eccentric, and discursive” — a space where music could short-circuit your brain and open up new ways of listening. It was a manifesto against the marketplace, a call for curiosity. The Krautrock Kompendium in Kolour is an essential, and beautiful, journey.

Nowhere is that clearer than in its filing system. “Our ‘subject headings’ reflect nothing but the Editor’s eccentricity and his love of taxonomy,” the manifesto explained. Issues divided reviews into categories with absurdly liberating structures. It advocated wandering.

That wandering made the magazine a kind of proto-recommendation engine. Each issue ran to hundreds of reviews, pointing out tapes, CD-Rs and small-press LPs you were unlikely to find anywhere else. Long before algorithms told you what to try next, The Sound Projector handed you lists of obscure, overlapping worlds.

The interviews catch that same energy, offering not just background but a sense of how music was being made in real time. One of the most revealing came in issue #8 (2000), with the late Peter Rehberg of Mego Records. Rehberg, born in London in 1968, had moved to Vienna as a teenager and spent years DJing, working in record shops and contributing to ORF radio before helping launch Mego in 1994 with Ramon Bauer and Andi Pieper.

The label quickly became a home for radical computer music, issuing work by Rehberg, Bauer, Fennesz, Tim Hecker and others at the moment laptops were emerging as instruments. Rehberg himself, performing solo as Pita and in collaboration with Bauer as General Magic, was among the first to demonstrate how portable computers could transform live electronic performance.

In this conversation he explains, with a mix of practicality and defiance, how laptop music functioned in the mid-1990s:

Ed Pinsent: How do you make your music? This may be a silly question… I know vaguely that you use the laptop…

Peter Rehberg: Yeah, laptops for playing live. Basically, like any form of electronic music using DATs, computers, samples… sample-based… it’s like doing tracks. Everyone… there’s been no real development, apart from the software, since Techno times — you know, the sequencer, the sampler, with which you created tracks. Nowadays it can all be done on one computer, you don’t need all these extra, peripheral units.

EP: So it’s better to do it on a laptop than to buy a separate sequencer…

PR: Yeah, we don’t need to. Everything’s built inside the software now. It’s not really necessary. Those people who want to have more analogue feeling… there are certain sounds which you can’t create on a laptop. But there are sounds which you can only create on a computer. We’ve chosen to go the computer way, because of practicability. And just general convenience, really.

EP: So how does it work when you play live?

PR: You’re running a patch, whether it’s Supercollider or Max, and this is… you have your own instrument. Ramon and me have our own Supercollider patch, which has a double loop reader where you can load four samples, make sequences and patterns, and it’s all real-time. So it’s like you have your own individual instrument on some machine. Machines which are all the same, so people who are against it say it was just something you bought in a shop! But it’s not. It’s all on the screen, it’s all… faders, and pushing buttons, and just like you would if you had a synthesiser — a handy package.

EP: And do all the Mego people use these laptops?

PR: Yes, Fennesz has a laptop, Hecker, Farmer’s Manual… basically, yes, everyone’s got laptops. I can’t think of anyone who doesn’t.

Rehberg’s answers now read like a hinge between eras, when laptop music was still new enough to require explanation.

The Sound Projector showed a particular devotion to Japanese experimental music, regularly carving out space for artists like Merzbow, Otomo Yoshihide, Masayuki Takayanagi and Sachiko M. Sections titled “Japanorama,” “Onkyo” and “Music From Japan” made clear that this wasn’t a passing fascination but a sustained effort to connect readers to one of the most vital avant-garde scenes of the era.

And then there was the look. The Sound Projector didn’t resemble anything else on the shelf. Its mix of cartoons, handwriting, typewritten text and collage gave the impression of a fanzine gone feral, but the density of its coverage was closer to an archive. That design wasn’t decoration — it is a statement. The pages reminded you that criticism could be idiosyncratic, playful, even unruly, yet still serious in intent. Each issue was both a guide and an object in itself, a map of listening drawn by hand.

The Sound Projector now lives on at Pinsent’s Sound Projector site and in the digital stacks of Archive.org, where the full run of the magazine can be read. From its launch in 1996 to its final edition in September 2022, Pinsent produced twenty-six issues, each one a dense, hand-built atlas of marginal sound. Seen together, their odd subject headings and cartoon frames form a complete vision. What once seemed impossibly esoteric — entire sections on Onkyo minimalism or Reynols’ Argentinian noise experiments — now reads like a roadmap to entire regions of music that remain vital and strange.

That spirit continues through The Sound Projector Radio Show on Resonance FM, which Pinsent still hosts with the same voracious curiosity. The broadcasts echo the magazine’s sensibility: sprawling playlists, rare finds, segues that only make sense in the moment. More than a continuation, the show demonstrates that The Sound Projector was never bound to print. It was always about listening in public, about turning discovery itself into an art.