The forecast is ominous: Sometime on Wednesday, the massive Hurricane Beryl, currently a category 4 storm, will likely hit Kingston, Jamaica with sustained winds of more than 145 […]

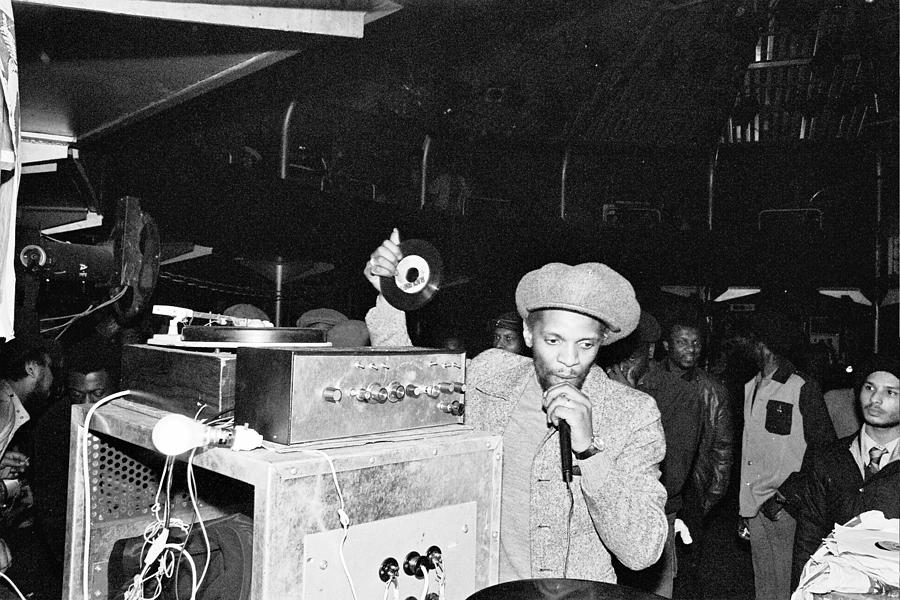

Zulu Warrior: Jah Shaka and His Spiritual Dub Soundsystem

A look into the great Zulu Warrior, legendary dub soundsystem operator and producer Jah Shaka.

“It’s something like seeing the Wizard of Oz for the first time; all that mighty, awesome thunder and noise of great rushing waters, then a faint start when you realise the tumult is coming from one man. All sound system followers have their favourites, and there is a certain section of the population who love only Shaka.”

So writes Vivien Goldman, British journalist, cult musician, former Flying Lizard, and dub aficionado. Most significant quotes detailing the experience of Jah Shaka and his mountainous system are similar: That Shaka seems to present the most profound connection to Rastafarian sound system culture, both its spiritual roots and essence; and that his all-consuming, chest-rattling system, combined with his messages of love, unity, and spirituality, converge to reveal a profound depth of sound.

Shaka remains a bit of a mystery. Few know his real name. Clues, though, reveal that Shaka was born in Clarendon Parish, Jamaica, an area synonymous with numerous roots reggae stars: legendary acts including Toots Hibbert, Everton Blender, Barrington Levy, and Freddie McGregor all rose from the neighborhood. Responding to an ad in the paper offering free transport to London for work, his family relocated to southeast London in 1956. Shaka was a teenager, and arrived during a time of rampant racism against black immigrants. His family and contemporaries were a part of the “Windrush generation,” named after a ship that had first docked in England in 1948 from Kingston.

Shaka recalled during an interview, “In the Windrush time, in London, on the doors of the houses, there were signs saying ‘no blacks, no Irish and no dogs.’ Growing up, our parents would tell us, ‘You have to work very hard to overcome such a system, such a regime.’”

Like many others embedded in this experience, families turned to building their own sound systems and throwing house parties as a means to escape their bigoted and impoverished reality. He further explained saying, “In the 1950s and 1960s in London, there were house parties – 50, 60 people with only record players. It helped families know other families, which was important at that time because the people were so forced to be segregated.”

Around this time, Shaka started studying under Freddie Cloudburst, a local speaker builder who hired him to polish his system and keep it pristine and presentable for his weekly shows. It soon led to him taking care of it – making sure the tube amplifiers and stacked walls of speakers were spotless and functional for every Cloudburst event. After years of maintenance work, Shaka had learned enough to know to build his own system, and was eventually granted permission to play some records at a bourgeois dancehall where Cloudburst had a residency.

By the 1970s, the “Shaka System” was in full effect, and Shaka had become a key figure within the British dancehall and dub scenes. Along the way, London turned into a hotbed for reggae culture, thanks to visionaries Shaka, Aba Shanti-I, and Channel One. Simultaneously, Downbeat The Ruler pioneered sound systems across the Atlantic in the United States.

Shaka’s system quickly gained a large and loyal following due to his unique mix of profoundly spiritual content, high-energy rhythms, and unmatched, sonorous sound. All of this was further complemented by Shaka’s dynamic personal style. Notably, that loyal following included many post-punk pioneers: Public Image Ltd, the Slits, and writer-musician Goldman among them.

The below video features a short interview with a local news station, where Shaka preaches his message as high-res footage shows his local dub party.

From a sound perspective, Shaka’s system could be so overwhelming that it induced transcendent states. To further cite Goldman’s beautiful writing on the ‘spiritual dub warrior’ and his expansive system, she recalls her personal experience:

“Then come certain sounds, the sounds that mark out Shaka. A keening sound cuts you, trailing a tail like a comet. Shaka playing his harp, then syn-drum; he hits it with a drumstick or plays it with his hands, the abstract texture melodies that race like liquid neon through each vein. This is a music, a great improvisation, that goes beyond reggae or any other musical division. Almost beyond physical music, into the mystic; sheets of energy shooting from the barricading standing store speakers.”

She continues, “Some people complain, say Shaka carries too much weight, too much distortion. It’s true it can verge on pain when Shaka shakes a sound by the scruff of its neck till it gives up its secret. But he is an extreme artist. Unlike most sound system organizers, he stays alone at the controls, speaking only when the spirit says so, choosing the music that will re-charge the people’s batteries like an orgone accumulator. If Shaka’s sound sticks needles in your ears, it’s like acupuncture, shaking up the sluggish circulation of the blood. He is a serious and dedicated man, who will only play inspirational music.”

Shaka was among the rarified few who could conjure this meeting of two extremes – mighty sound matched with an equally compelling message. His events attracted a diverse audience, and his dub parties brought in numbers previously unimaginable for the genre – a testament to the message that he expounds, his choice of music, and his deeply felt Rastafarian beliefs.

Because of this, his influence would be largely felt by a range of genres to come, from Jungle to ghetto-style dub that would soon follow. Christopher Patridge, a professor at Lancaster University, interviewed and sat in on a panel with Jah in 2012, who has this to say of his influence, style, and message:

“Shaka played down to earth, heavyweight, ‘warrior style’ dub that conveyed a certain charismatic integrity. Although I have no doubt that there are a number of sociological and musicological reasons for this perception of integrity, it seems to me that it has always had something to do with his approach to dub. Shaman-like, he seemed to operate at the nexus of this world and some other elusive, Rastafarian reality. Like a worshipper before an icon, his focus was not on the art as such, but on that which lay beyond it. Dub was a gateway to the sacred; a window on Zion; a channel of the divine. Consistently articulating his vocation in terms of consciousness raising, he has always been clear about his desire to increase the general level of ‘overstanding’ about Rastafari, social justice, education, the promotion of peace and the celebration of unity. The fact that listening to his music happens to be a pleasurable experience is important, not only because he genuinely wants people to enjoy themselves, but, more significantly, because this makes it an effective medium for the message of Jah. His music is, therefore, integral to his mission. Having borrowed the name Shaka from a revolutionary, early nineteenth century Zulu warrior, he developed an understanding of dub as a weapon in the service of Rastafari, of Africans (particularly the African diaspora), and, finally, of all humanity. Whereas other media can be suppressed and controlled by Babylon, Shaka’s sound system is direct action against oppression, misinformation and ignorance. Powerful stepper’s riddims and sonorous floor-shaking bass call for revolution—peaceful revolution.”

After 50 odd years, the enigmatic Zulu Warrior continues to travel with his epic “shaka system.” Uncompromisingly spreading his music, messages of love, and spirituality to this day.

Below, watch Shaka himself informatively break down the history of UK sound system culture at Red Bull Music Academy.