’90s era trip-hop blues and Japanese exotica from guitarist Shunji Mori. The seemingly endless well of ’90s CD-era Japanese downtempo bands continues to reveal new secrets… Our latest […]

Cracked Loops and Collapsed Cities: The Story of Illbient in 5 Tracks

DJ Olive, We™, DJ Wally, DJ Spooky, and others turned dub, decay, and sample science into something stranger than genre.

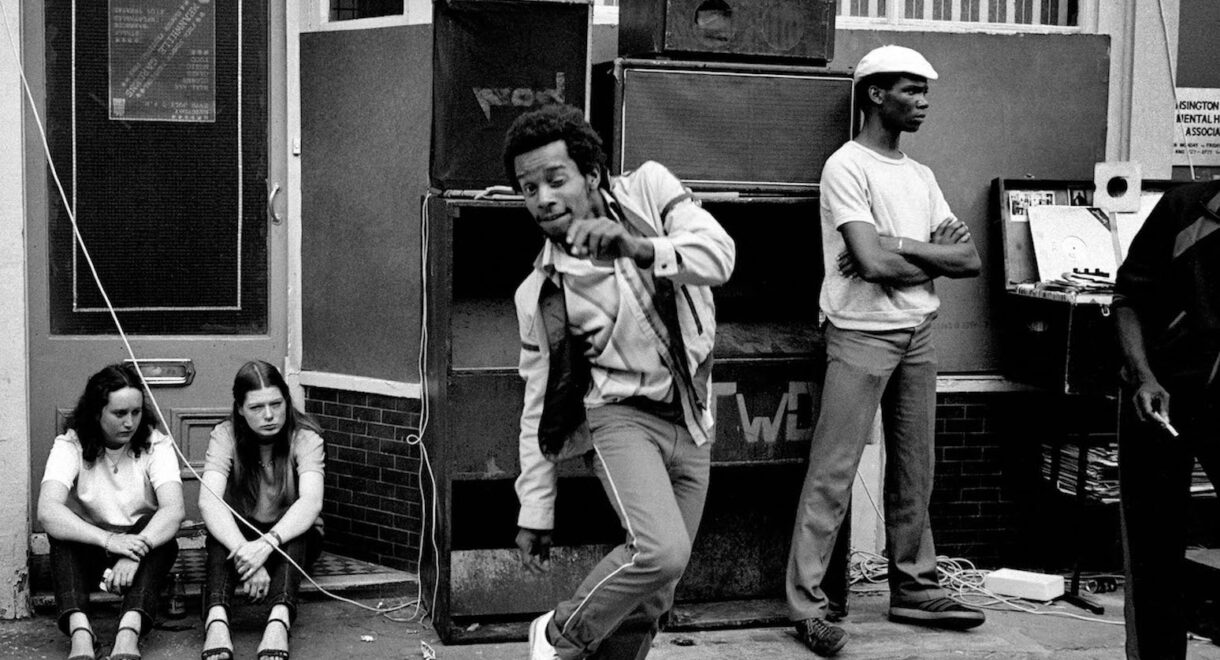

In the twilight of the 20th century, before streaming, algorithmic curation, and genre tags hardened into digital cement, a shadowy, bass-heavy strain of electronic music boomed to life in the warehouses, art lofts, and back rooms of downtown New York and Brooklyn. It didn’t have a clear name at first, but it had an atmosphere. Dense, foreboding mood stitched together from ambient drift, hip hop’s skeletal rhythms, dub’s sense of vastness, and the sonic detritus of a wild city surrounding them. It was too heady to dance to, too beat-heavy to ignore, and too strange to fit neatly anywhere. Eventually, someone called it illbient, which seemed to work.

“The term illbient was a joke I told a reporter, English guy,” Gregor Asch of We™ said in an oral history of Illbient published by Red Bull Music Academy. “We were at a party called Molecular at the Gas Station listening to Akin Adams, from Byzar. He was playing bass on a chair in a puddle of water through some effects and two amps to the surrounding bleeding sound from the other people playing in the room. The reporter asked, ‘Is this ambient?’ and I replied, ‘No, man, this is fuckin illbient.’”

Others remember it differently: “After graduating, I moved to New York and started writing for The Village Voice and The Source,” Paul D. Miller, a.k.a. DJ Spooky, said to Red Bull. “Illbient was a term I was using at the time for fun and kicks. I didn’t think anything of it, but I was using it actively.”

Regardless of the genesis, centered around a loose, shape-shifting crew of producers, DJs, and conceptual troublemakers, illbient emerged as a conscious friction between sound and noise, structure and sprawl, the club and the gallery. Artists like DJ Spooky, Spectre, and DJ Olive had ideas beyond music, constructing haunted cities out of samples and space.

“I’d use tape wire to make the tone arm skip so as to imitate a sampler,” Asch said. “Play house records at 16 RPM, using these fucked up granny turntables with speakers on the side, and skip them to get different sounds. Repeat that with other records and you’d get a weird synch. Once you got five going, it was pretty psychedelic. I would also make grilled cheese sandwiches while DJing, which at 4 AM was pretty great.”

Labels like Wordsound (New York) and Asphodel (San Francisco) acted like cryptic dispatch services, pressing records and CDs that sounded like pirate radio beamed from a dystopian future. Rooted in dub and hip-hop but animated by collage, performance art, and Afrofuturist poetics, illbient was less a genre than a weather system: humid, unstable, and always on the verge of breaking into storm.

Below, some portals for you to enter.

We™ – As Is (Asphodel, 1997)

A record as vaporous as it is rhythmic, As Is comes from the trio We™ — Gregor Asch (aka DJ Olive), Lloop, and Once11 — who approached illbient not as a genre but as a process: layer, erode, repeat. These weren’t club tracks so much as sedimentary forms, built from dub pulses, broken vinyl loops, and incidental noise. “By combining samples that sounded cool to us,” Asch said, “we achieved something greater than the sum of its parts.” The trio drew from hip-hop, acid, musique concrète, and stray artifacts — Varèse, King Tubby, early Air Liquide — mixing them until things got strange. “Some people would get a kind of vertigo from it.” As Is remains one of the genre’s most refined statements: meditative but grounded, beat-based but barely tethered. Listening feels like walking through a city at 4 a.m.

DJ Spooky – Songs of a Dead Dreamer (Asphodel, 1996)

DJ Spooky (Paul D. Miller) brought theory to the turntables. Songs of a Dead Dreamer isn’t just a debut — it’s a manifesto, a beat-driven essay on memory, technology, race, and the collapsing boundaries of genre. Sampling William S. Burroughs one minute and tweaking a dusty break the next, Spooky treated sound as raw data for cultural recombination. He called his method “illbient,” but also “rhythm science” — a practice as informed by Deleuze and Barthes as by Kool Keith and King Tubby. The record flows like an academic mixtape: cryptic, moody, overstuffed, and full of friction.

Not long after Songs of a Dead Dreamer, Spooky teamed up with UK sound artist Scanner for The Quick and the Dead, a tense, flickering dialogue between American collage and British surveillance aesthetics. Where Spooky sampled theory and jazz, Scanner embedded intercepted cell phone conversations and electronic static. The result feels like an espionage film melting in a lecture hall: disorienting, cerebral, and stitched with dread.

DJ Wally – The Stoned Ranger Rides Again (Liquid Sky Music, 1996)

DJ Wally, aka Keef Destefano, came at illbient sideways — less from theory, more from record store intuition and stoner instinct. The Stoned Ranger Rides Again is his most iconic release, and the one that captures his sly, unhurried approach: hip-hop drums left half-limp in the pocket, loops that crackle like they’ve been recycled too many times, and jazz samples warped just enough to feel off-kilter. Compared to Spectre’s paranoia or Spooky’s philosophy, Wally was looser, funnier, a little more daydreamy — but no less strange. The result is an album that’s intimate, weed-fogged, and deeply textured.

Sub Dub – Dancehall Malfunction (WordSound, 1997)

Dancehall Malfunction is the most agitated entry in Sub Dub’s small but seismic catalog. Where other illbient records smolder, this one shudders. Built from raw drum machines, cavernous bass, and blown-out delay, it sounds like a sound system devouring itself in real time — dancehall riddems pulled through a filter of industrial static and spiritual unrest. John Ward and Raz Mesinai keep the mix unstable, constantly ducking between hard groove and dub disintegration. The result is tightly wound, physical, and off-center, like Lee Perry scoring a sci-fi film with a broken MPC.

Badawi – Bedouin Sound Clash (Roir, 1996)

Before illbient had a name, Sub Dub’s Mesinai was already tracing its outlines. Music for Meditation 1988–1993, recorded while he was still a teenager, captures his early experiments with hand percussion, tape looping, and long-form ritual—music intended more for trance than for tape release. That foundation gave Bedouin Sound Clash, his first album under the Badawi name, a depth and authority few peers could match. Where others leaned on collage, Mesinai built from lineage: Middle Eastern modes, heavy dub, and industrial grit woven into something at once ancient and electrical. Bedouin Sound Clash isn’t aggressive so much as possessed, like sacred music overheard through a cracked speaker. It stands not just as a landmark illbient record, but as a personal mythology rendered in rhythm.