A look into the young label behind the first-ever official reissues of Les Rallizes Dénudés and Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Surround. Temporal Drift is an independent record label launched by […]

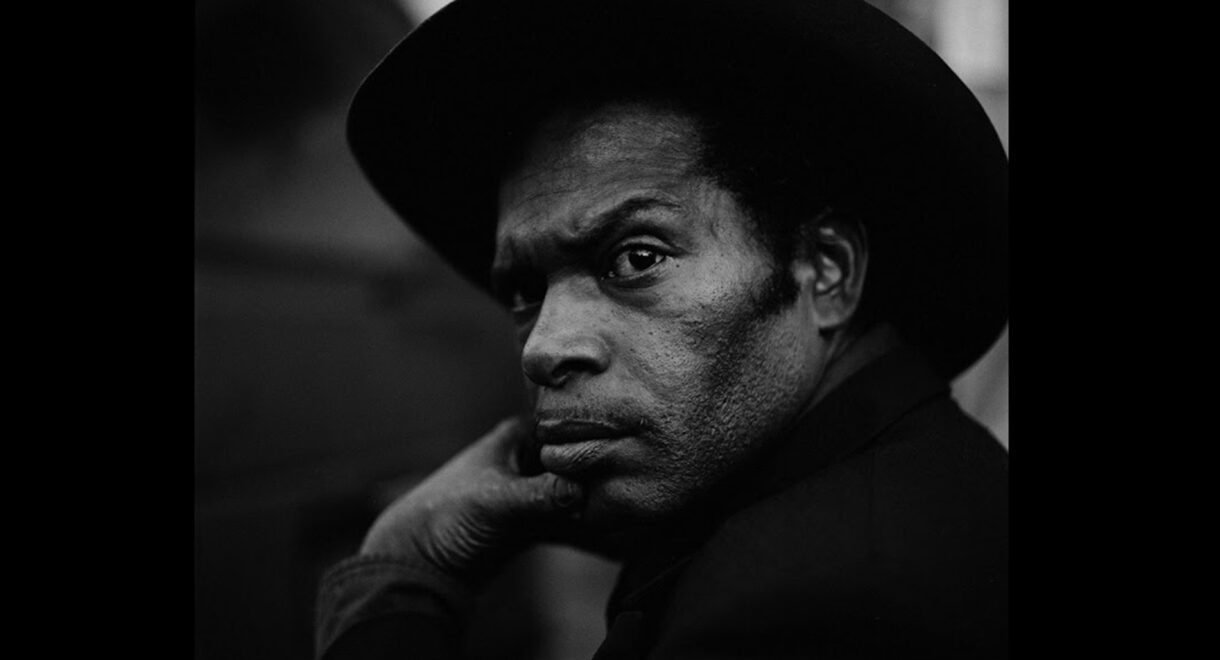

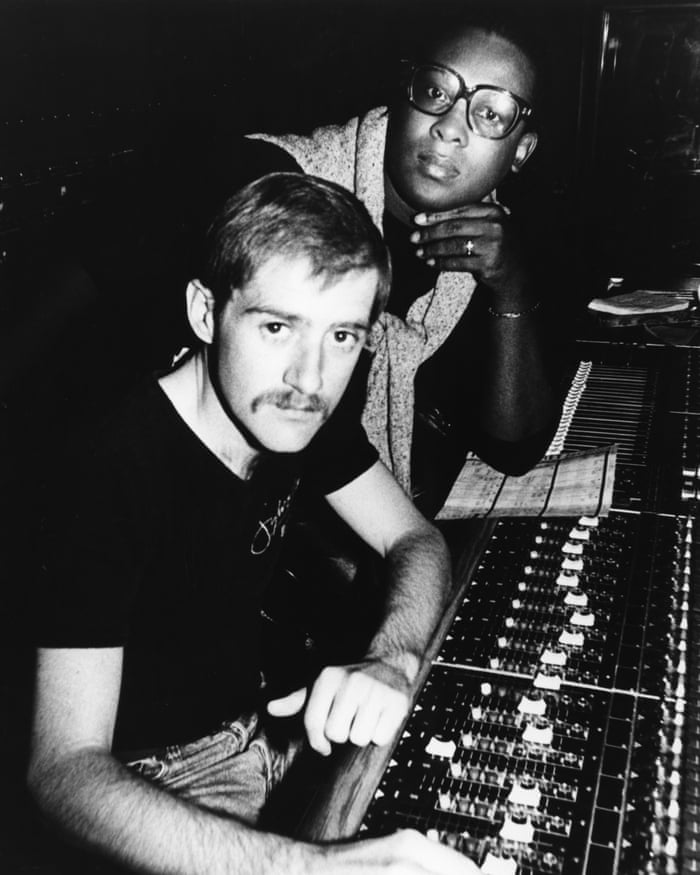

In Conversation: The Lost Tapes of Patrick Cowley with Dark Entries’ Josh Cheon

Tana Yonas speaks to the Dark Entries label boss on Patrick Cowley and the importance of archiving.

Music archivists and researchers often work in the shadows. For some, their sole intent may be to captivate audiences, and for others it’s to keep the soul of brilliant pieces of music alive. Josh Cheon is guided by both, and since he founded Dark Entries in 2009 he’s worked to new layers to the stories of each release. Josh started the label a few years after joining Honey Soundsystem, a DJ collective responsible for the contemporary disco revival in San Francisco.

Together they stumbled across a piece of San Francisco history that would change their lives: an unreleased record by Patrick Cowley, the iconic synth player and hi-NRG innovator. It was Catholic, a new wave/synth pop masterpiece recorded 1976.

Below, we talk to Josh about how he ended up involved with the legacy of Patrick Cowley, and how Patrick’s unapologetically gay dance floor anthems inspired the British new wave movement though artists like New Order and The Pet Shop Boys.

When you started Dark Entries, was it something you were thinking about for a while, or did it just happen by accident?

It had been something I’ve been thinking about for quite a while. The inspiration was to reissue underground, out of print, unreleased music from the ’80s as well as contemporary music that references the ‘80s synthesizer-based sounds that I love. My initial goal was to put out a reissue and then follow it up with a contemporary record. But I had so many reissues that it became my focus with a splattering of contemporary stuff along the way.

What made the ‘80s so special musically?

Well, there were a lot of new instruments that were becoming more affordable for people. There were synthesizers in the ‘70s but they were really expensive and massive so they weren’t accessible or portable. Only really big bands and studios could afford them. As the ’80s progressed, it was much easier to get a synthesizer, or even build one yourself. They got more affordable and portable, and I think it really changed the whole landscape of music. They’re all new sounds musicians were able to make, and new drum machines were also coming out on the market. It was a really fertile time. Now, everything that is being made is still using those same core instruments, even if it’s the software-based stuff.

It seems like there has been a renaissance of like reissues, and each label has its own style and vibe. After following you for a while, it seems like your releases really speak to you individually as a person. Is that right?

Yeah, I don’t reissue anything I don’t love or am passionate about. I just don’t reissue things just for the sake of reissuing it. It has to have a story or call to me and resonate with me in order for me to start the journey of the reissuing process, which is sometimes really long and a lot of work.

And yeah, it’s always a bonus if I find out that they’re gay. It has always resonated with me because I’m gay too. I get to tell a history that’s part of me, and one that has been swept under the rug. A lot of times these musicians were in the closet or they’re no longer with us because they passed away for various reasons, whether it’s AIDS, drugs or whatever. They’re definitely the marginalized stories that are lost to the ethos. I don’t even think they make it into the history books.

I think this, in a way, is preserving these stories and keeping these

histories alive and showing them to a new generation. A lot of these underground queer bands couldn’t get a record deal back then, and so a lot of it just never was released, or it might have come out with only 500 copies on a very underground label. So it’s nice for these bands to have a second chance in a way.

Was there a unique musical perspective the gay community cultivated in the 80’s?

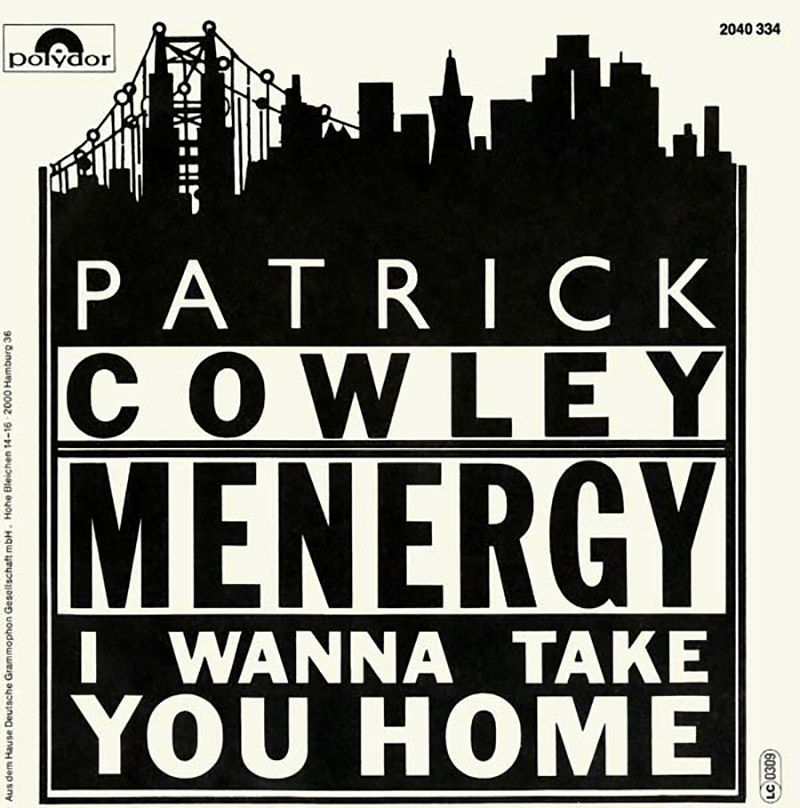

Definitely. The hi-NRG sound that Patrick Cowley came up with definitely was attributed to the gay discos at the clubs. They had dance charts just for the hi-NRG sound in the 80s, which is synonymous with “the gay sound.”

They had the big disco demolition night in ‘79, where they burned all the records in Chicago at the Cubs Stadium. And it was kind of signaling the end of disco, but the gays were like, “No, we’re not done.” They weren’t going to abandon disco just because these right-wing evangelical people were telling them to stop. Part of what they were protesting against that day in Chicago was that disco was too gay. So I think hi-NRG arose out of the gays not being done with disco. They updated it and made it a little more electronic sounding and more robotic. Disco wasn’t dead. That’s just one of many sounds that gay people are responsible for, of course originally house and techno were all gay and black musicians who invented all of the stuff we take for granted now.

And yeah, as I’ve learned through research at the label, there are great gay porn soundtracks that were predominantly made by gay men, and forgotten about or they were made under a pseudonym so people didn’t know who was making the music. It was kind of still illegal in a majority of the states. I have more gay porn soundtrack reissues plans for the future.

I was reading that Patrick Cowley was one of those musicians who produced a a lot of music for gay porn, and you were able to access some this unreleased music. How did you unearth those recordings?

Well, in 2007, Honey Soundsystem was contacted by John Hedges, the former owner of Megatone Records. Patrick Cowley co-founded the label with Marty Blecman in ‘81. Patrick passed away in ‘82, and John Hedges took over after Marty passed away later in the ‘80s. John was retiring to Palm Springs and called all the local SF DJs over to his house to clear out all of his vinyl; he didn’t want to take any of it with him.

Honey Soundsystem was brand new at that time; and because we were the new kids on the block, we were invited over last. We fortunately had the foresight to say, “You know what, we’ll take everything. Let’s preserve everything even though we don’t want all of this.” There were all these sealed Megatone records, and we just took it all because we realized the importance of having an archive.

Part of what was left were these milk crates with reel to reels. Some of them had Patrick Cowley’s music on them, and so we had two of the tapes transferred. That ended up being the unreleased Patrick Cowley’s album Catholic. We ended up giving it to a German company called Macro in 2008, who released the CD version.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6198344-1413504551-4551.jpeg.jpg)

We held a party to celebrate the release on Patrick Cowley’s 59th birthday, and I was really bummed that we gave up this amazing record to the Germans. Dark Entries hadn’t started until 2009, so we had given it to them. So I basically went into overdrive, contacting all of Patrick’s friends, his families, lovers, roommates and co-musicians; and I interviewed as many as I could. I recorded all these interviews, and we had them playing over headphones at a party. We had drag performances and it was a really amazing, very history-focused night of Patrick Cowley’s life.

At the party, these two guys came up to me and said, “Hey, have you found Patrick’s porn soundtracks?” And I said, “wait … no.” They told me, “Yeah, he made music for gay porn.” I told them I had just interviewed 40 or more people and no one mentioned anything about it. And I learned he hadn’t told many people about it; but he had told them. Back then if you Googled, “Patrick Cowley porn” nothing online comes up.

So then how did you end up locating the recordings?

Well, there was a guy in New York named Brian that ran a gay porn music blog. And I think he had found an instrumental version of “Somebody To Love Tonight” by Sylvester in a gay porn. It sounded like a demo, you know, a little rougher. When I heard it, I said to myself, “Oh my gosh, maybe that is. Maybe that’s the porn soundtrack Patrick produced.” I ordered a copy on DVD and I listened to it and said, “Wow, this does sound like Patrick”; at least parts of it did.

I ended up tracking down the director who’s still alive, and after a year of back and forth, I flew down to Los Angeles. We dug around in his storage garage and we found all the reels of music Patrick Cowley had mainly made for the films he made. The majority of it Patrick had laying around, and had made it when he was in college. He just gave it to the guy to use and modify for scenes.

Watch the video for Patrick Cowley’s “Deep Inside You” here.

It seems like this idea of archival or archiving is a recurring theme in this conversation. Where do you think that desire comes from for you? Why is it so important for you to archive and share these mostly forgotten moments in music?

I find it fascinating, and I just love seeing all the connections. In the case of someone who’s more like a household name like Patrick Cowley, who is known for this hi-NRG sound, I find all of these tapes of this very slow, very funky, esoteric music he made to soundtrack these gay porns. It’s like, wait, that was never part of his story publicly.

I think that happens with all of us, we have so many facets to our lives. We only show part of that to the outside world. And so I feel like, in part, I’m the custodian of Patrick Cowley’s music. But also I have to consider, would he have wanted all of this music to come out? Like, am I doing him justice? People love it, but would Patrick have wanted to ever release all of this music that I’m choosing to release. It’s kind of a big responsibility and a question that I have to ask myself.

Thankfully his friends and his family are still with us so I can pass ideas by them and get their input. But yeah, I see a value in preserving these stories and uncovering new stories. I mean, I just love digging and contacting the artists to get liner notes from them; any kind of photos and memories. I think it’s important to include the voice of the artists when possible, with every issue.

I feel like so many times when labels do reissues they’re just slapping some artwork together and regurgitating the same old thing. Yes, it serves a purpose of getting the music out there on vinyl or digital but you’re missing the soul of the artists. With each record I try to preserve that and pass on the primary source, which is the artist and their voice — whether it’s through a photo or even a quote, or if they’re willing to write notes. Yeah, I find that definitely important for my label, and it’s something I’ve been doing since day one.

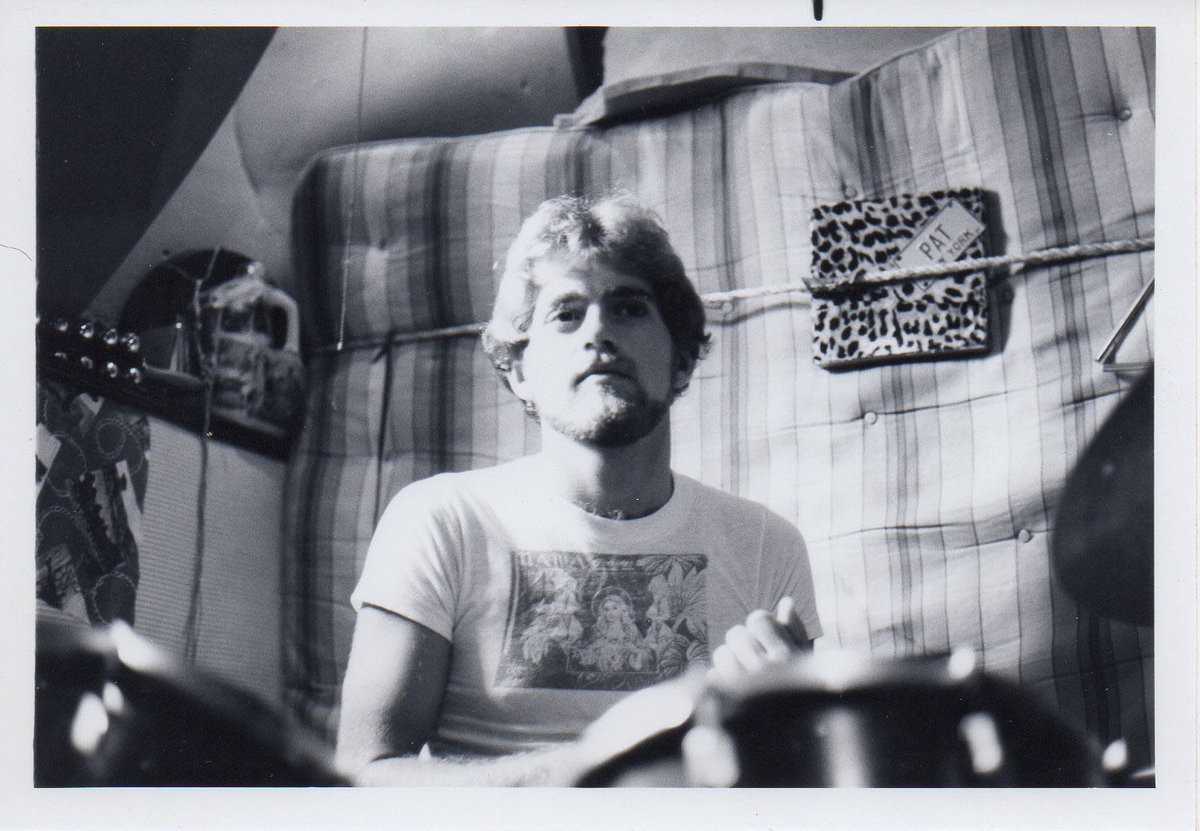

You shared on Instagram recently that Patrick Cowley had his most prolific years after he was diagnosed with HIV early in the crisis. Was there also change in his sound during this period?

Yeah, and that also goes back to the advent of the instruments that were coming out. So as the 70s came to an end and the 80s these synthesizers were being mass-produced and were more accessible. Patrick never really had a lot of money so when he did get a check from selling a bunch of records, he would spend it all on either a piece of equipment or a new studio. Then he would be kind of broke. His studio wasn’t really full of fancy synthesizers either. But he learned how to layer instruments to create bigger sounds with his simple setup.

He would do tricks where he would have 8 tracks, then he would record everything on six tracks and then bounce them down and put them on two of the tracks. And then out of the eight tracks, two of them would already have bounced down music from the previous mix down. It would just look like eight tracks but they were really 14 tracks of music.

For his final album, Mindwarp, he had access to a 24-track studio. He was too sick to do any of the mixing, but they were able to create a huge sound with those 24 tracks. You can have so much more stuff going on, which didn’t always make it better. Some of his earlier ideas were getting drowned out by new things coming into the mix. Recently, I’ve come across a lot of his demos from his early recordings and I shared them online. I sent it to the musicians who were around him and heard things like, “Wow, he sounds so much better. Why didn’t he put out this version? Why did we re-record this drum and why did we leave out that synthesizer sound?” So now I’m learning that sometimes having more actually made things sound different than what he initially set out to achieve.

Did you ever learn what equipment he used?

In the early days he was using equipment from his college. He was enrolled at City College San Francisco and he had access to their synthesizer lab. Those were all plug and play — a giant Putney and an E-MU analog with patches and chords. It was like the Delia Derbyshire BBC Radiophonic sound. When was able to get his studio, he had the early Roland CR-78 drum machine, a Prophet-5, the ARP-2600, ARP Solina Strings and he had a lot of effects boxes that he ran things through.

But passing away in 1982, right, when all of these things were coming on the market, it’s so tragic that he wasn’t able to keep making music because so many more synthesizers were coming just after he passed away.

Did hi-NRG help the mainstream accept gay culture?

I don’t know. It definitely was mined by straight people and musicians to advance their sounds like with New Order. Pet Shop Boys have been very vocal about listening to hi-NRG music and being heavily influenced by Patrick Cowley specifically. A lot of people might have not known that a Pet Shop Boys track is basically a Patrick Cowley song. New Order were obsessed with Patrick’s remix of “I Feel Love,” and that inspired parts of “Blue Monday,” and so many things.

So to try to answer your question, I don’t know if it helps. Maybe subconsciously because people were listening to it, but it was without realizing that their favorite British pop band were inspired by gay hi-NRG music.

You said that Patrick started Megatone Records with Marty Blecman. How did their label shape the hi-NRG scene?

Well, they were one of the first labels to primarily release all hi-NRG music. Because Patrick Cowley released his records there, it kind of became home to all of the music influenced by Patrick. After he passed they tried to keep the label going by mimicking Patrick’s blueprint but they never really had any more hits after that. I think ‘Do You Wanna Funk’ was probably the last big hit they had, and that was right as Patrick died.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1014551-1184262297.jpeg.jpg)

I think again, because we were losing vast amounts of gay musicians in the ‘80s, it definitely got co-opted by straight people who were surviving and not being affected by AIDS. And so it became embraced by the straights because to them they’re saying to themselves, “Hey, this is making money. This is a thing and the gays will buy it.” It was like, the blueprint was made and let’s just keep repackaging it.

I don’t think Patrick would have kept making hi-NRG records. I think he definitely would have branched out. And he tried to with the Catholic record. He wanted that to come out but no one would release it. It was too weird. I think it was something that he was going to do on his label because he couldn’t get anyone to put it out in ‘79 before he had Megatone Records.

Licensing seems like one of the most difficult parts of reissuing something. Is it as difficult as it seems?

It varies. Obviously, I would much rather deal with the artists if they control their rights. Like there’s one German company who owns most of the Italo Disco in the world, but do they really own it? I find the artists, and then they tell me I have to license it from this German company that’s pretty evil. They actually restarted their Italo disco vinyl pressing, and now they’ve just been churning out like so many records every month, plowing through their own catalog. It kind of cuts out all the licensing. Now I’m nervous to email them for a license. It just feels like they’re going to take my request and then just going to do it themselves.

There’s also stories of me flying to Spain, and knocking on an artist’s door begging them to let me do reissues. I have so many crazy stories of getting a record out.

Did you kind of have an idea of the vinyl pressing world before you went to press your first record? Can you kind of speak to the actual pressing of the vinyl that you released?

Yeah, I mean, all my records are pressed at the same pressing plant in Los Angeles called RTI. They’re easily one of the best pressing plants in America, if not the world. I’m very lucky that I was turned on to them from day one because I didn’t know anything about pressing plants or quality. My old roommate, who ran a record label before me, to me that I had to go through RTI in Los Angeles and use Dorado to make my jackets. He gave me what he was using for his vinyl and I just ran with it. And I really lucked out that it was, and still is, such a great pressing plant. What’s the point of putting all this work and money into a product that doesn’t sound good or might have flaws because it’s rushed.

Have you ever considered putting out a blank record with pirated copies of records?

No way, I would never do that. I’m always criticizing all those labels that do that, especially when they’re coming after artists on my label or my friends. Some people say it’s been happening forever, but so have reissues. I feel like changing the name and calling it an edit or whatever is lazy.

There are a bunch of records that I’ve been trying to work on for years. I have a wish list and I know some of them will never happen.

I've always been curious, was your logo for Dark Entries inspired by the Megatone Records logo?

It wasn’t at all, it was actually inspired by Bauhaus Design Company. The name “Dark Entries”, came from a Bauhaus song so I knew my logo had to be Bauhaus design.

I saw this old ad about Bauhaus and used this as a base to build my logo from. I literally just turned their design into a D and an E for Dark Entries.

What’s your next release?

I guess just the one that just came out just came out January 15th and was really a long, long, long time coming. It’s a band from Cleveland called Sexual Harassment. Not the greatest name, but I don’t think they expected to get as huge as they did. And it was kind of like tongue in cheek because of course sex sells. They’re an amazing group from the 80s and they became more famous later because artists like Egyptian Lover covered their songs “I Need a Freak”.

And the next record I have coming out is by a musician from Oakland. His name’s Dax Pierson and it’s his debut album, Nerve Bumps. It’s out on February 26, and it’s really forward-thinking techno and definitely very synth-heavy. He was in a hip hop group in the early 2000s, so it definitely has elements of hip hop with a kind of cut up, almost jazz-like percussion to it. I’m excited about that.